This month we dove into a classic technology strategy book. The book covers seven major Powers a company can have that offer both a benefit and a barrier to competition. Helmer covers the majority of the book through the lens of different case studies including his favorite company, Netflix.

Tech Themes

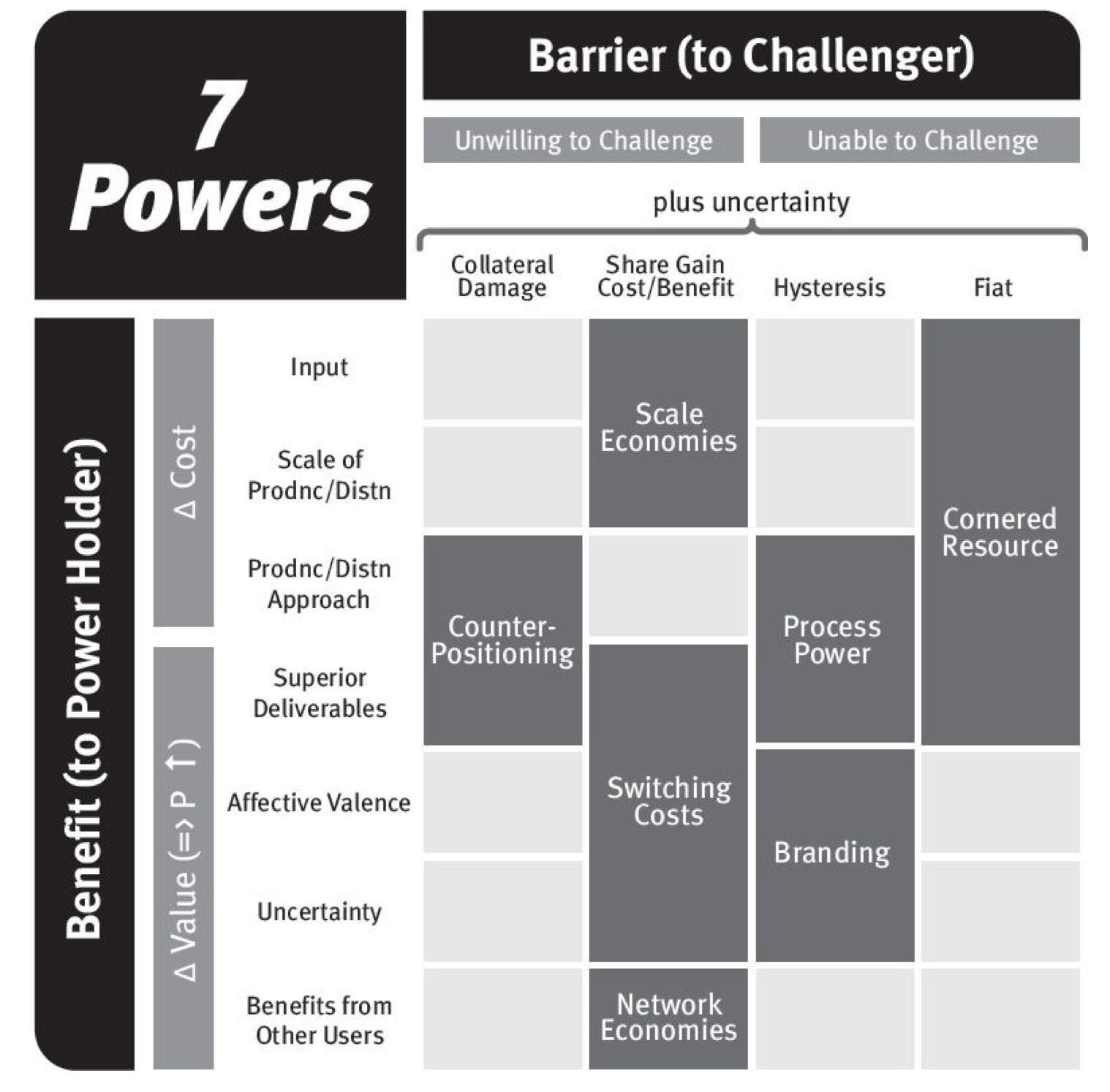

Power. After years as a consultant at BCG and decades investing in the public market, Helmer distilled all successful business strategies to seven individual Powers. A Power offers a company a re-inforcing benefit while also providing a barrier to potential competition. This is the epitome of an enduring business model in Helmer's mind. Power describes a company's strength relative to a specific competitor, and Powers focus on a single business unit rather than throughout a business. This makes sense: Apple may have a scale economies Power from its iPhone install base relative to Samsung, but it may not have Power in its AppleTV originals segment relative to Netflix. The seven types of Powers are: Scale Economies, Network Economies, Counter-Positioning, Switching Costs, Branding, Cornered Resources, and Process Power.

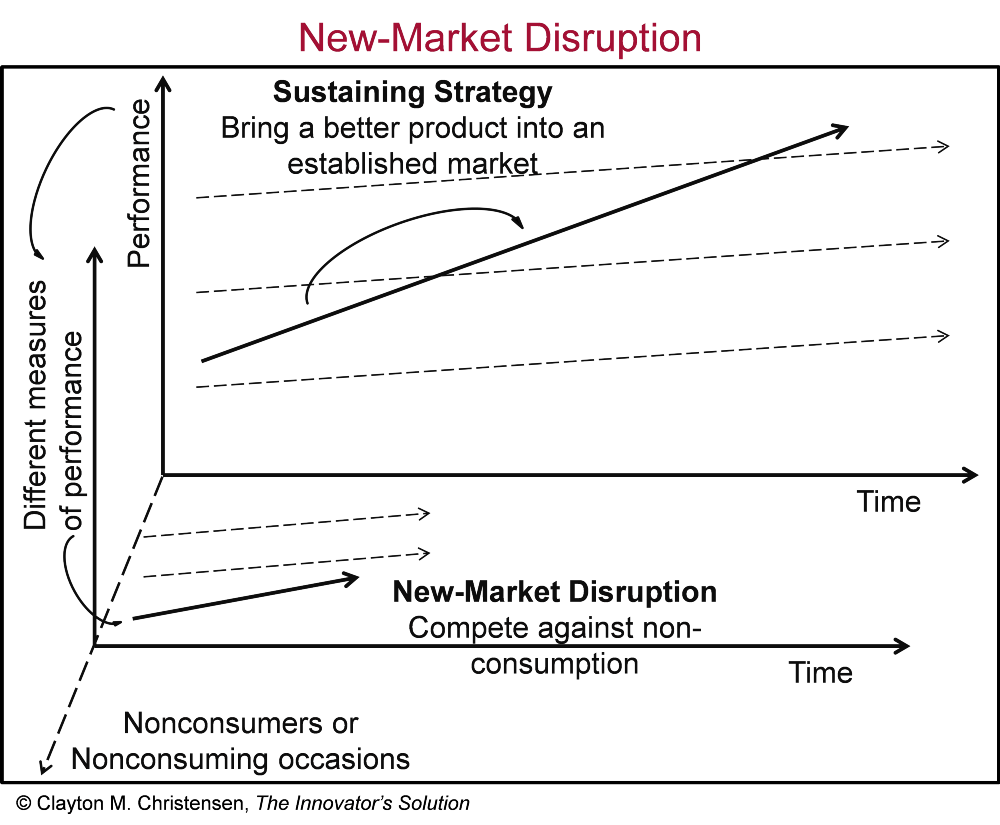

Invention. While Powers are somewhat easy to spot (scale economies of Google's search algorithm), creating them is anything but easy. So what underlies every one of the seven Powers? Invention. Helmer pulls invention through the lens of industry Dynamics - external competitive conditions and the forward march of technology create opportunities to pursue new business models, processes, brands, and products. Companies must leverage their resources to craft Powers through trial and error, rather than an upfront conscious decision to pursue something by design. I view this almost as an extension of Clayton Christensen's Resource-Processes-Values (RPV) framework we discussed in July 2020. Companies can find a route to Power through these resources and the crafting process. For Netflix, the route was streaming, but the actual Power came from a strong push into exclusive and original content. The streaming business opened up Netflix's subscriber base, and the content decision provided the ability to amortize great content across its growing subscriber base.

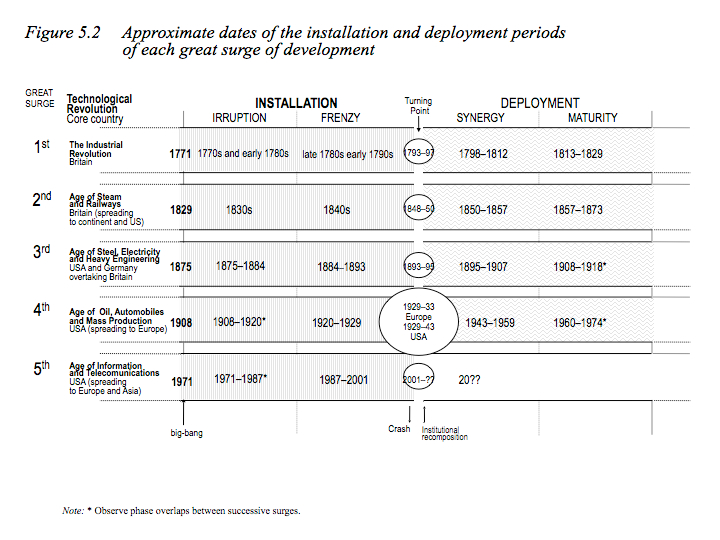

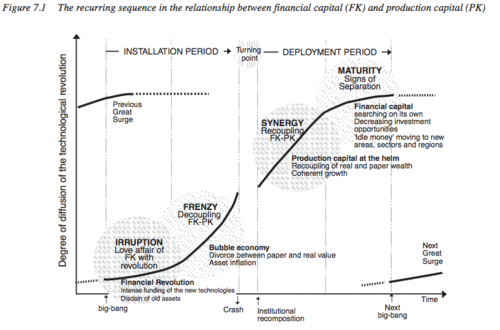

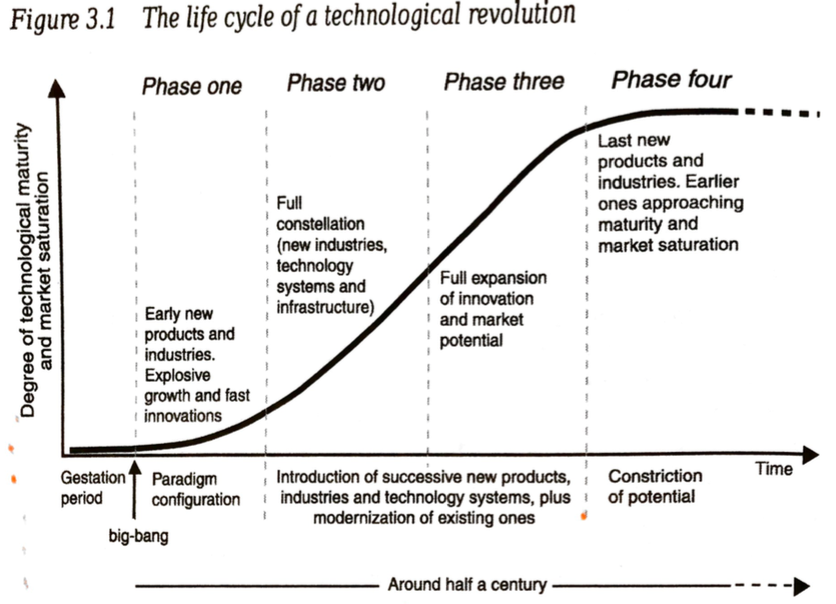

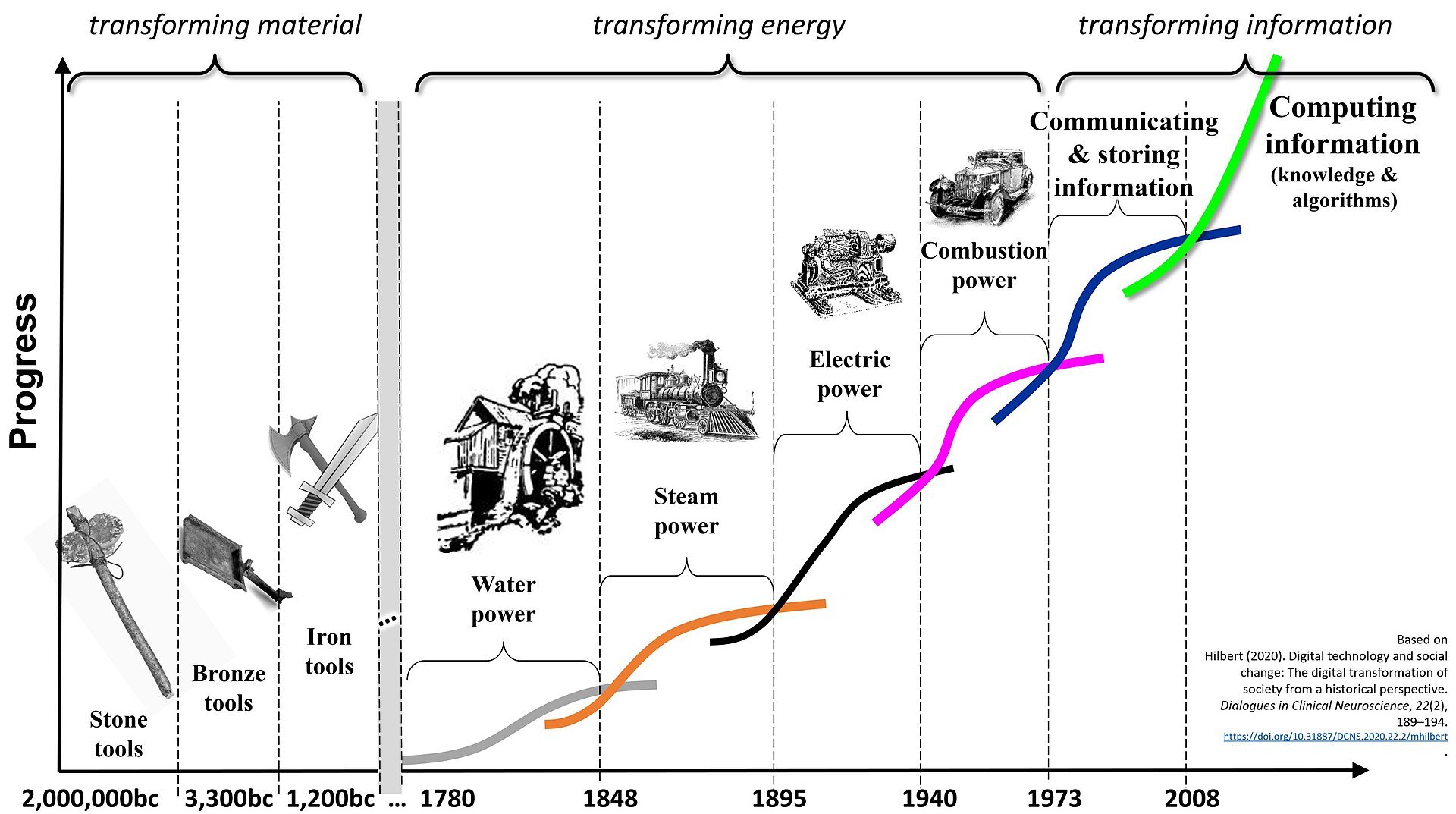

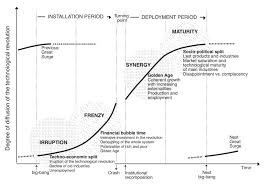

Power Progressions. Powers become available at different points in business progression. This makes sense - what drives a company forward in an unpenetrated market is different from what keeps it going during steady-state - Snowflake's competitive dynamics are different than Nestle's. Helmer defines three stages to a company: Origination, Takeoff, and Stability. These stages mirror the dynamics of S-Curves, which we discussed in our July 2021 book. During the Origination stage, companies can benefit from Cornered Resources and Counter-Positioning. Helmer uses the Pixar management team as an example of Cornered Resources during the Origination phase of 3D animated movies. The company had Steve Jobs (product visionary), John Lasseter (story-teller creative), and Ed Catmull (operations and technology leader). During the early days of the industry, these were the only people that knew how to operate a digital film studio. Another Cornered Resource example might be a company finding a new oil well. Before the company starts drilling, it is the only one that can own that asset. An example of Origination Counter-Positioning might be TSMC when they first launched. At that time, it was standard industry perception that semiconductor companies had to be integrated design manufacturers (IDM) - they had to do everything in-house. TSMC was launched as solely a fabrication facility that companies could use to gain extra manufacturing capacity or try out new designs. This gave them great Counter-Positioning relative to the IDM's and they were dismissed as a non-threat. The Takeoff period offers Network Economies, Scale Economies, and Switching Cost Powers. This phase is the growth phase of businesses. Snowflake currently benefits from Switching Cost dynamics - once you use Snowflake, it's unlikely you'll want to use other data warehouse providers because that process involves data replication and additional costs. Scale economies can be seen in businesses that amortize high costs over their user base, like Amazon. Amazon invests in distribution centers at a significant scale, which improves customer experience, which helps them get more customers - the flywheel repeats, allowing Amazon to continually invest in more distribution centers, further building its scale. Network economies show in social media businesses like Bytedance/TikTok. Users make content that attracts more users; incremental users join the platform because there is so much content to "gain" by joining the platform. Like scale economies, it's almost impossible to go build a competitor because a new company would have to recruit all users from the other platform, which would cost tons of money. The Stability phase offers Branding and Process Power. Branding is hard to generate, but the advantage grows with time. Consider luxury goods providers like LVMH; the older, the more exclusive the brand, the more it's desired, and every day it gets older and becomes more desired. A business can create Process Power by refining and improving operations to such a high degree that it becomes difficult to replicate. Classic examples of Process Power are TSMC's innovative 3-5nm processes today and Toyota's Production System. Toyota has even allowed competitors to tour its factory, but no competitor has replicated its operational efficiency.

Business Themes

Sneak Attack. I've always been surprised by businesses that seemingly "come out of nowhere." In Helmer's eyes, this stems from Counter-Positioning. He tells the story of Vanguard, which was started by Jack Bogle in 1976. "You could charitably describe the reception as enthusiastic: only $11M trickled in from investors. Soon after the launch, [Noble Laureate Paul] Samuelson himself lauded the effort in his column for Newsweek, but with little result: the fund had only reached $17M by mid-1977. Vanguard's operating model depended on others for distribution, and brokers, in particular, were put off by a product that predicated on the notion that they provided no value in helping their clients choose which active funds to select." But Vanguard had something that active managers didn't: low fees and consistency. Vanguard's funds performed like the indices and cost much less than active funds. No longer were individuals underperforming the market and paying advisors to pick actively managed funds. Furthermore, Vanguard continually invested all profits back into its funds, so it looked like it wasn't making money while it grew its assets under management. It's so hard to spot these sneak attacks while they are happening. But one that might be happening right now is Cloudflare relative to AWS. Cloudflare launched its low-cost R2 service (a play on Amazon's famous S3 storage technology). Cloudflare is offering a cheaper product at a much lower cost and is leveraging its large installed base with its CDN product to get people in the door. It's unclear whether this will offer Power over AWS because it's confusing what the barrier might be other than some relating to switching costs. However, there will likely be reluctance on AWS's part to cut prices because of its scale and public company growth targets.

A New Valuation Formula. Helmer offers a very unique take on the traditional DCF valuation approach. Investors have long suggested the value of any business was equal to the present value of its future discounted cash flows. In contrast to the traditional approach of summing up a firm's cash flows and discounting it, Helmer takes a look at all of the cash flows subject to the industry in which firms compete. In this formula (shown above), M0 represents the current market size, g the discounted market growth factor, s the long-term market share of the company, and m the long-term differential margin (net profit margin over that needed to cover the cost of capital). More simply, a company is worth it's Market Scale (Mo x g) x its Power (s x m). This implies that a company is worth the portion of the industry's profits it collects over time. This formula helps consider Power progression relative to industry dynamics and company stage. In the Origination stage, an industry's profits may be small but growing very quickly. If we think that a competitor in the industry can achieve an actual Power, it will likely gain a large portion of the long-term market. Thus, watching market share dynamics unfold can tell us about the potential for a route to Power and the ability for a company to achieve a superior value to its near-term cash flows.

Collateral Damage. If companies are aware of these Powers and how other companies can achieve them, how can companies not take proactive action to avoid being on the losing end of a Power struggle? Helmer lays out what he calls Collateral Damage, or the unwillingness of a competitor to find the right path to navigating the damage caused by a competitor's Power. His point is actually very nuanced - it's not the incumbent's unwillingness to invest in the same type of solution as the competitor (although that happens). The incumbent's business gets trashed as collateral damage by the new entrant. The incumbent can respond to the challenger by investing in the new innovation. But where counter-positioning really takes hold is if the incumbent recognizes the attractiveness of the business model/innovation but is stymied from investing. Why would a business leader choose not to invest in something attractive? In the case of Vanguard competitor Fidelity, any move into passive funds could cause steep cannibalization of their revenue. So in response, a CEO might decide to just keep their existing business and "milk" all of its cash flow. In addition, how could Fidelity invest in a business that completely undermined their actively managed mutual fund business? Often CEOs will have a negative bias toward the competing business model despite the positive NPV of an investment in the new business. Just think how long it took SAP to start selling Cloud subscriptions compared to its on-premise license/maintenance model. Lastly, a CEO might not invest in the promising new business model if they are worried about job security. This is the classic example of the principal-agent problem we discussed in June. Would you invest in a new, unproven business model if you faced a declining stock price and calls for your resignation? In addition, annual CEO compensation is frequently tagged to stock price performance and growth targets. The easiest way to achieve near-term stock price appreciation and growth targets is staying with what has worked in the past (and M&A!). Its the path of least resistance! Counter-positioning and collateral damage are nuanced and difficult to spot, but the complex emotions and issues become obvious over time.