This month we read a short, under-discussed book by current Snowflake and former ServiceNow and Data Domain CEO, Frank Slootman. The book is just like Frank - direct and unafraid. Frank has had success several times in the startup world and the story of Data Domain provides a great case study of entrepreneurship. Data Domain was a data deduplication company, offering a 20:1 reduction of data backed up to tape casettes by using new disk drive technology.

Tech Themes

Data Domain’s 2008 10-K prior to being acquired

First time CEO at a Company with No Revenue. Frank is an immigrant to the US, coming from the Netherlands shortly after graduating from the University of Rotterdam. After being rejected by IBM 10+ times, he joined Burroughs corporation, an early mainframe provider which subsequently merged with its direct competitor Sperry for $4.8B in 1986. Frank then spent some time at Compuware and moved back to the Netherlands to help it integrate the acquisition of Uniface, an early customizable report building software. After spending time there, he went to Borland software in 1997, working his way up the product management ranks but all the while being angered by time spent lobbying internally, rather than building. Frank joined Data Domain in the Spring of 2003 - when it had no customers, no revenue, and was burning cash. The initial team and VC’s were impressive - Kai Li, a computer science professor on sabbatical from Princeton, Ben Zhu, an EIR at USVP, and Brian Biles, a product leader with experience at VA Linux and Sun Microsystems. The company was financed by top-tier VC’s New Enterprise Associates and Greylock Partners, with Aneel Bhusri (Founder and current CEO of Workday) serving as initial CEO and then board chairman. This was a stacked team and Slootman knew it: “I’d bring down the average IQ of the company by joining, which felt right to me.” The Company had been around for 18 months and already burned through a significant amount of money when Frank joined. He knew he needed to raise money relatively soon after joining and put the Company’s chances bluntly: “Would this idea really come together and captivate customers? Nobody knew. We, the people on the ground floor, were perhaps, the most surprised by the extraordinary success we enjoyed.”

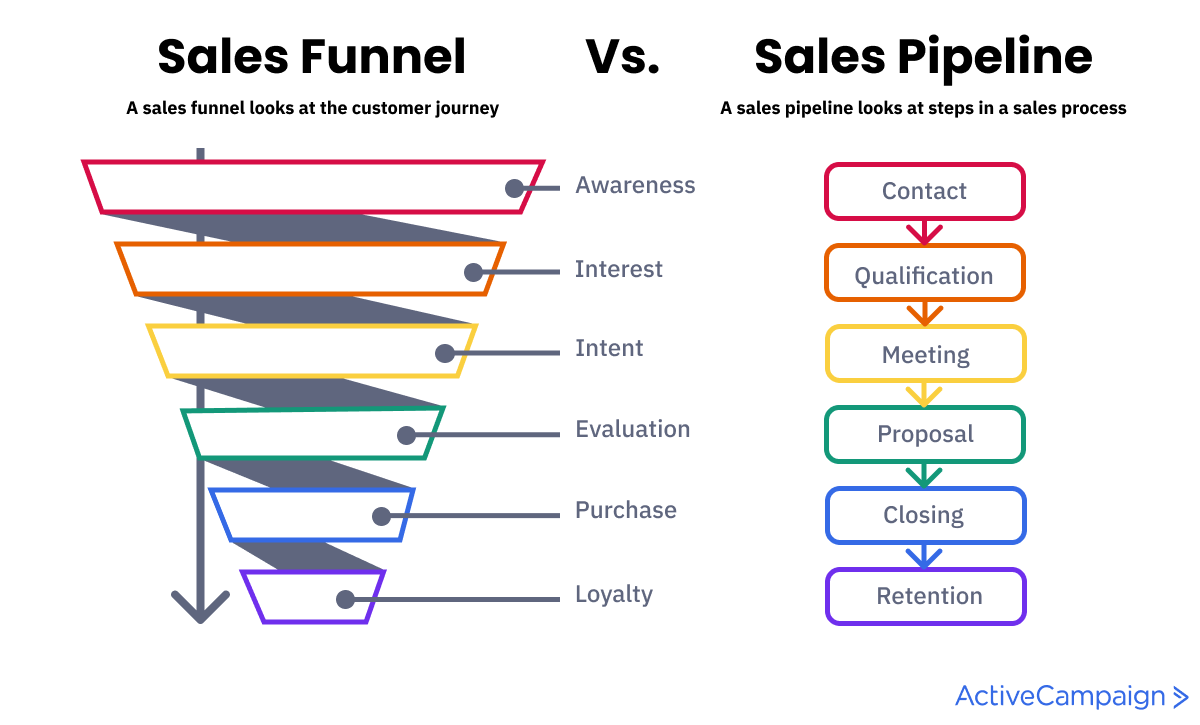

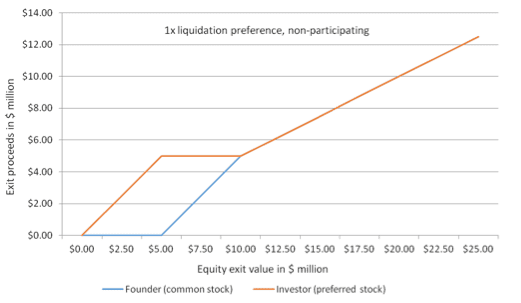

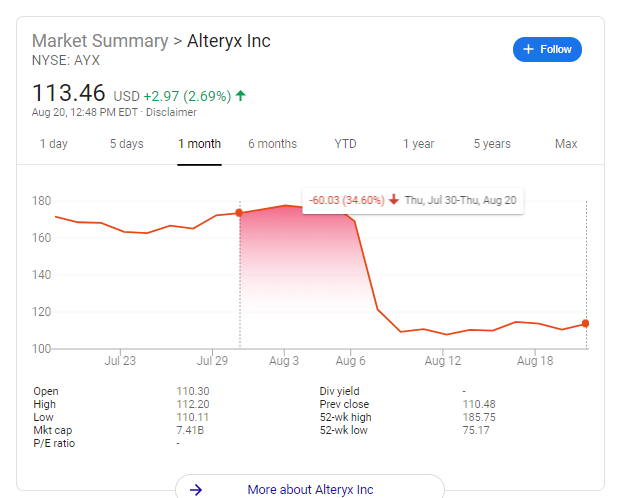

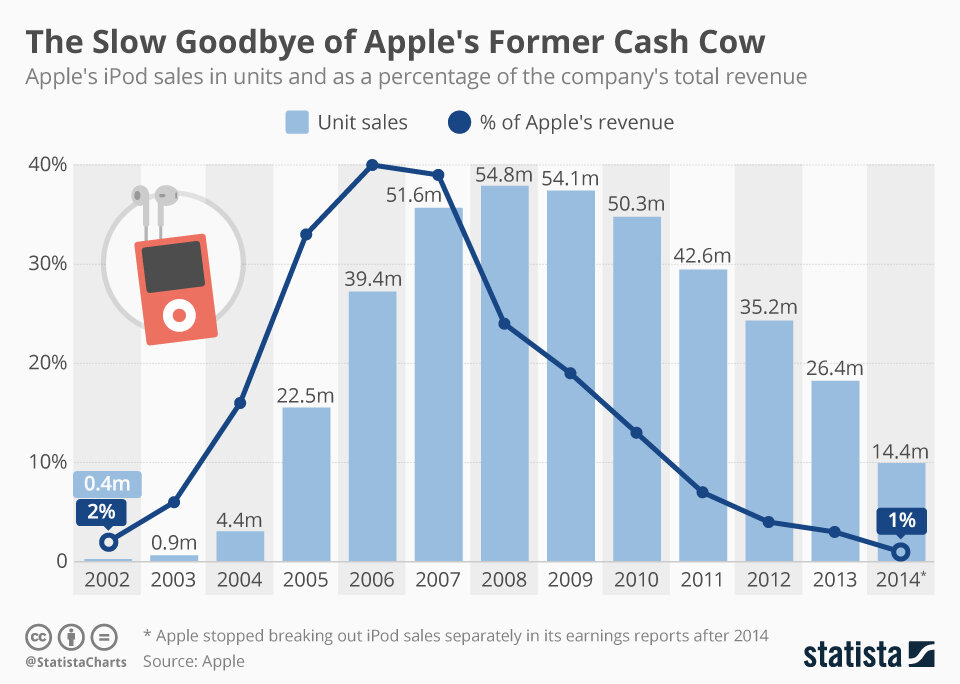

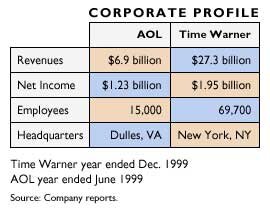

Playing to his Strengths: Capital Efficiency. One of the big takeaways from the Innovators by Walter Issacson was that individuals or teams at the nexus of disciplines - primarily where the sciences meet the humanities, often achieved breakthrough success. The classic case study for this is Apple - Steve Jobs had an intense love of art, music, and design and Steve Wozniak was an amazing technologist. Frank has cultivated a cross-discipline strength at the intersection of Sales and Technology. This might be driven by Slootman’s background is in economics. The book has several references to economic terms, which clearly have had an impact on Frank’s thinking. Data Domain espoused capital efficiency: “We traveled alone, made few many-legged sales calls, and booked cheap flights and hotels: everybody tried to save a dime for the company.” The results showed - the business went from $800K of revenue in 2004 to $275 million by 2008, generating $75M in cash flow from operations. Frank’s capital efficiency was interesting and broke from traditional thinking - most people think to raise a round and build something. Frank took a different approach: “When you are not yet generating revenue, conservation of resource is the dominant theme.” Over time, “when your sales activity is solidly paying for itself,” the spending should shift from conservative to aggressive (like Snowflake is doing this now). The concept of sales efficiency is somewhat talked about, but given the recent fundraising environment, is often dismissed. Sales efficiency can be thought of as: “How much revenue do I generate for every $1 spent in sales and marketing?” Looking at the P&L below, we see Data Domain was highly efficient in its sales and marketing activity - the company increased revenue $150M in 2008, despite spending $115M in sales and marketing (a ratio of 1.3x). Contrast this with a company like Slack which spent $403M to acquire $230M of new revenue (a ratio of 0.6x). It gets harder to acquire customers at scale, so this efficiency is supposed to come down over time but best in class is hopefully above 1x. Frank clearly understands when to step on the gas with investing, as both ServiceNow and Snowflake have remained fairly efficient (from a sales perspective at least) while growing to a significant scale.

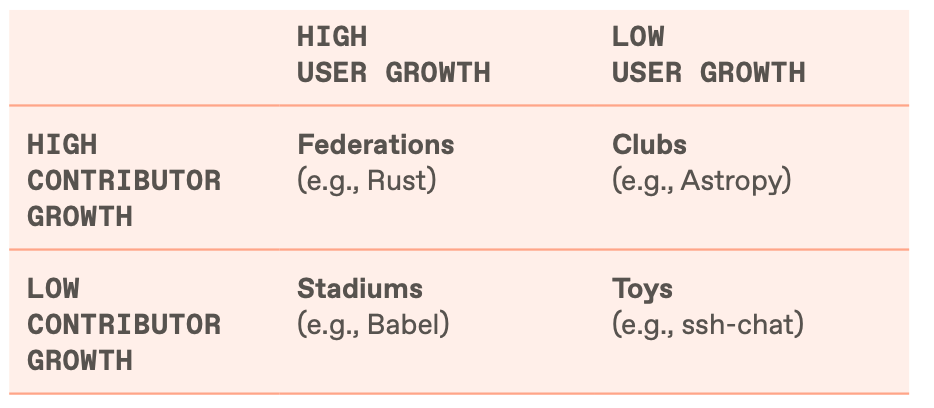

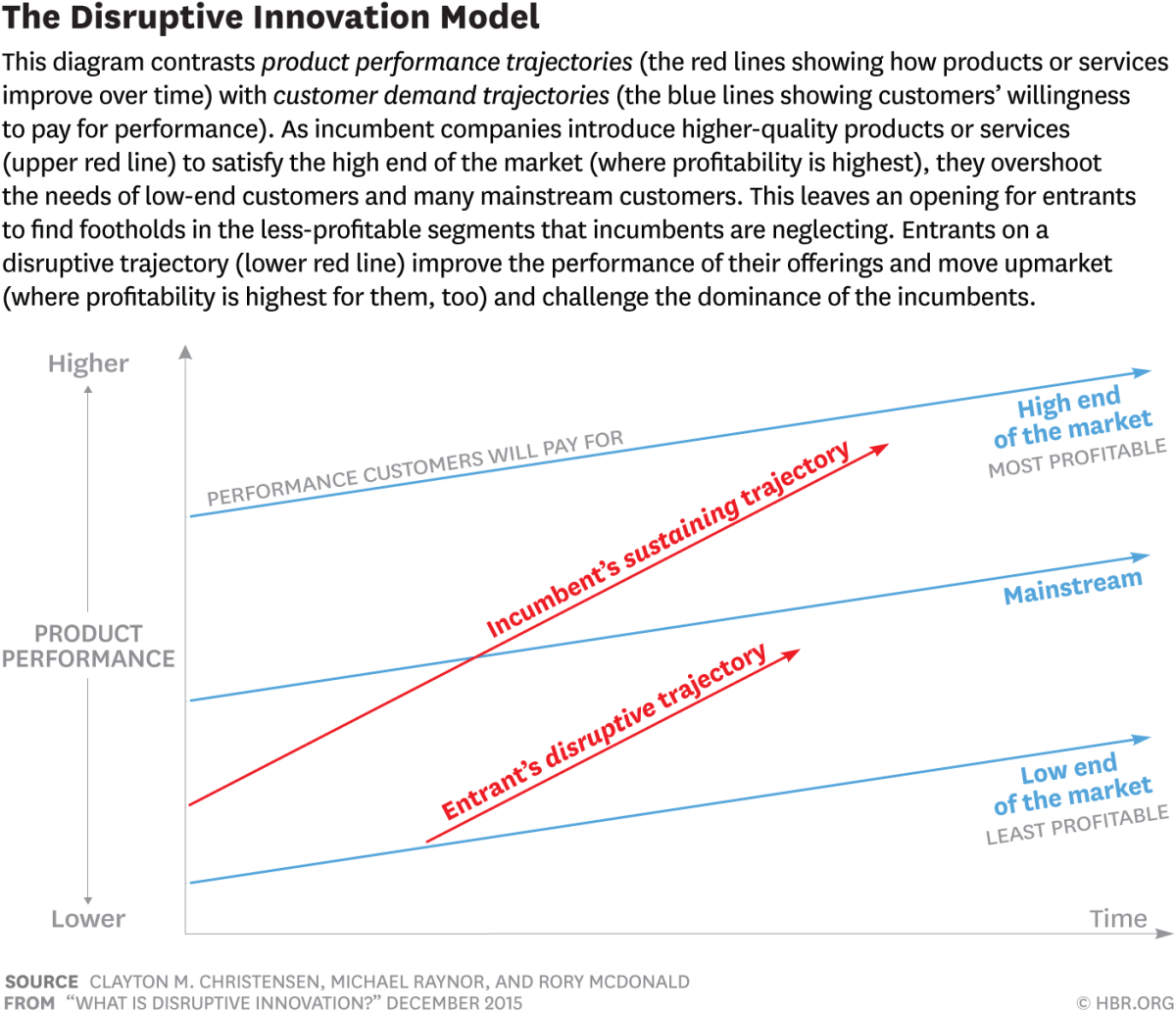

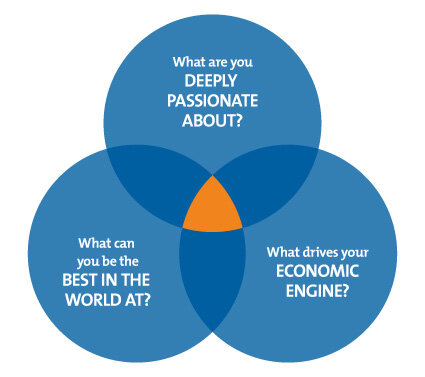

Technology for Technology’s Sake. “Many technologies are conceived without a clear, precise notion of the intended use.” Slootman hits on a key point and one that the tech industry has struggled to grasp throughout its history. So many products and companies are established around budding technology with no use case. We’ve discussed Magic Leap’s fundraising money-pit (still might find its way), and Iridium Communications, the massive satellite telephone that required people to carry a suitcase around to use it. Gartner, the leading IT research publication (which is heavily influenced by marketing spend from companies) established the Technology Hype Cycle, complete with the “Peak of inflated expectations,” and the “Trough of Disillusionment” for categorizing technologies that fail to live up to their promise. There have been several waves that have come and gone: AR/VR, Blockchain, and most recently, Serverless. Its not so much that these technologies were wrong or not useful, its rather that they were initially described as a panacea to several or all known technology hindrances and few technologies ever live up to that hype. Its common that new innovations spur tons of development but also lots of failure, and this is Slootman’s caution to entrepreneurs. Data Domain was attacking a problem that existed already (tape storage) and the company provided what Clayton Christensen would call a sustaining innovation (something that Slootman points out). Whenever things go into “winter state”, like the internet after the dot-com bubble, or the recent Crpyto Winter which is unthawing as I write; it is time to pay attention and understand the relevance of the innovation.

Business Themes

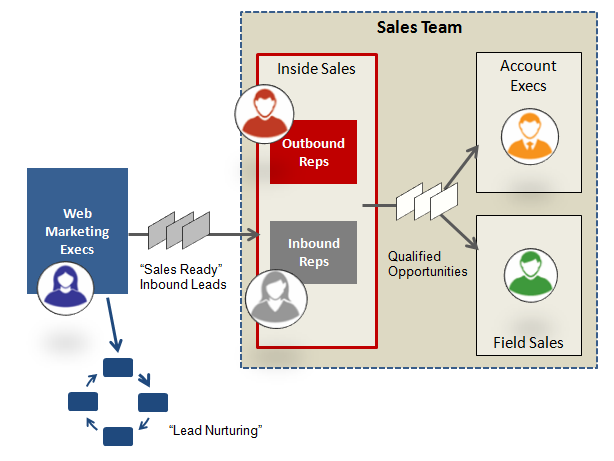

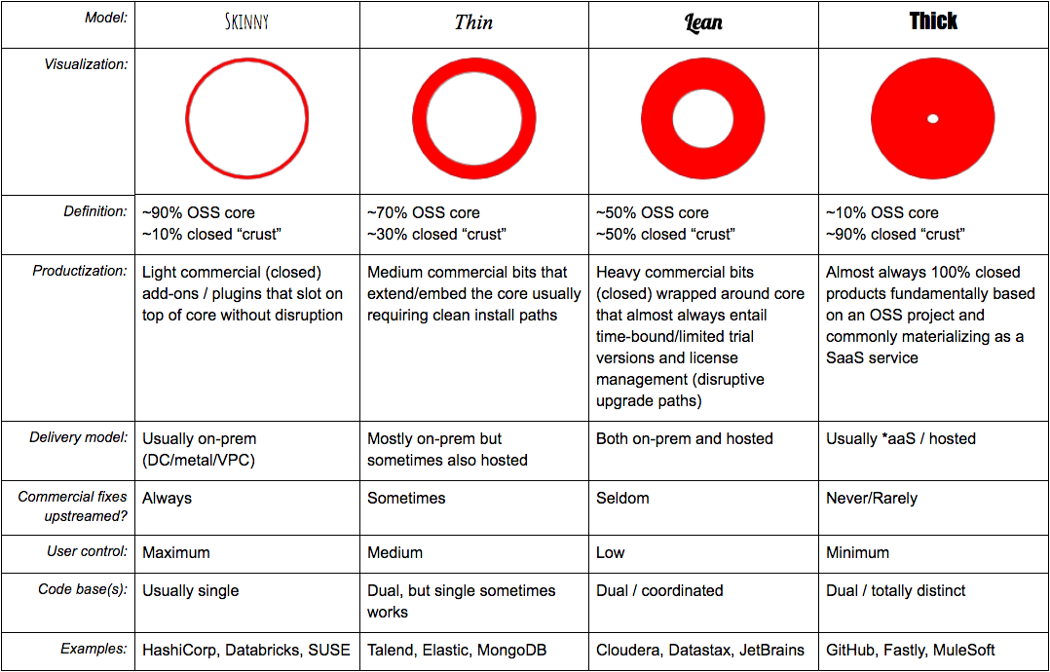

Importance of Owning Sales. Slootman spends a considerable amount of this small book discussing sales tactics and decision making, particularly with respect to direct sales and OEM relationships. OEM deals are partnerships with other companies whereby one company will re-sell the software, hardware, or service of another company. Crowdstrike is a popular product with many OEM relationships. The Company drives a significant amount of its sales through its partner model, who re-sell on behalf of Crowdstrike. OEM partnerships with big companies present many challenges: “First of all, you get divorced from your customer because the OEM is now between you and them, making customer intimacy challenging. Plus, as the OEM becomes a large part of your business, for all intents and purposes they basically own you without paying for the privilege…Never forget that nobody wants to sell your product more than you do.” The challenges don’t end there. Slootman points out that EMC discarded their previous OEM vendor in the data deduplication space, right after acquiring Data Domain. On top of that, the typical reseller relationship happens at a 10-20% margin, degrading gross margins and hurting ability to invest. It is somewhat similar to the challenges open-source companies like MongoDB and Elastic have run into with their core software being…free. Amazon can just OEM their offering and cut them out as a partner, something they do frequently. Partner models can be sustainable, but the give and take from the big company is a tough balance to strike. Investors like organic adoption, especially recently with the rise of freemium SaaS models percolating in startups. Slootman’s point is that at some point in enterprise focused businesses, the Company must own direct sales (and relationships) with its customers to drive real efficiency. After the low cost to acquire freemium adopters buy the product, the executive team must pivot to traditional top down enterprise sales to drive a successful and enduring relationship with the customer.

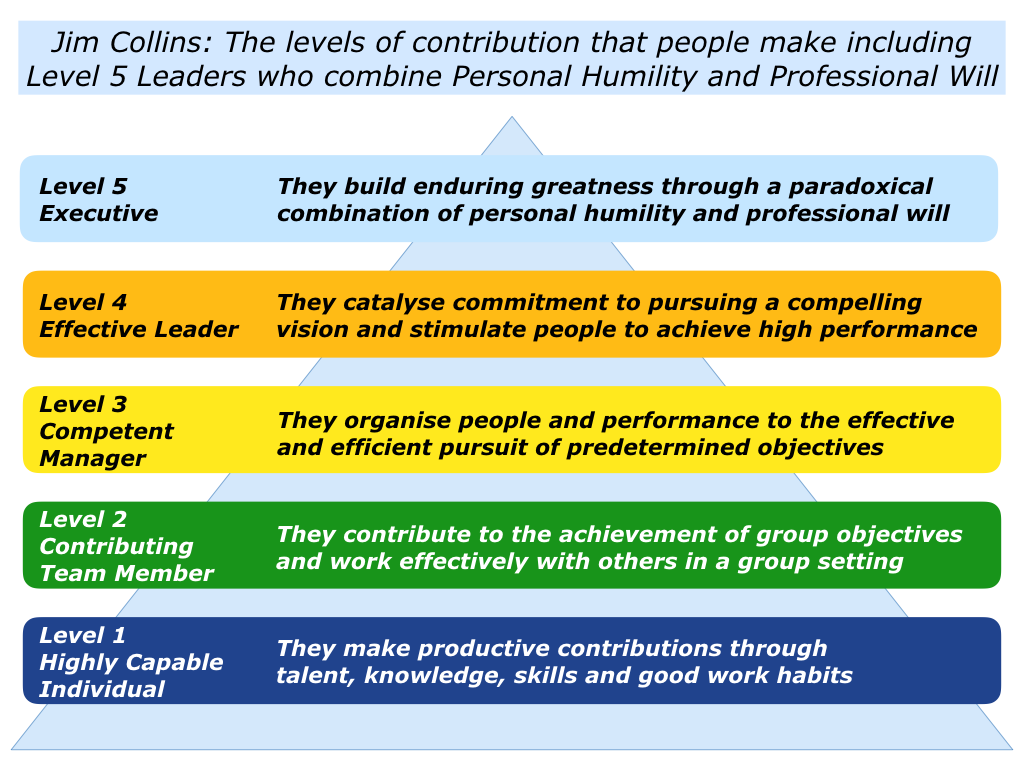

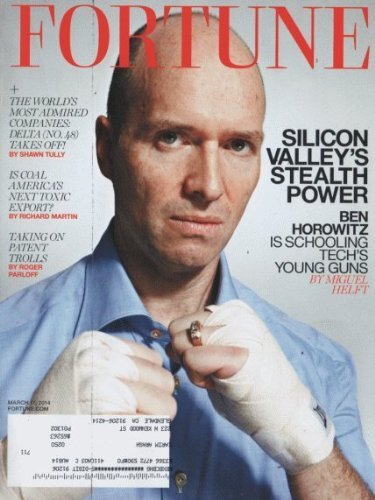

In the Thick of Things. Slootman has some very concise advice for CEOs: be a fighter, show some humanity, and check your ego at the door. “Running a startup reduces you to your most elementary instincts, and survival is on your mind most of the time…The CEO is the ‘Chief Combatant,’ warrior number one.” Slootman views the role of CEO as a fighter, ready to be the first to jump into the action, at all times. And this can be incredibly productive for business as well. Tony Xu, the founder and CEO of Doordash, takes time out every month to do delivery for his own company, in order to remain close to the customer and the problems of the company. Jeff Bezos famously still responds and views emails from customers at jeff@amazon.com. Being CEO also requires a willingness to put yourself out there and show your true personality. As Slootman puts it: “People can instantly finger a phony. Let them know who you really are, warts and all.” As CEO you are tasked with managing so many people and being involved in all aspects of the business, it is easy to become rigid and unemotional in everyday interactions. Harvard Business School professor and former leader at Uber distills it down to a simple phrase: “Begin With Trust.” All CEO’s have some amount of ego, driving them to want to be at the top of their organization. Slootman encourages CEO’s to be introspective, and try to recognize blind spots, so ego doesn’t drive day-to-day interactions with employees. One way to do that is simple: use the pronoun “we” when discussing the company you are leading. Though Slootman doesn’t explicitly call it out - all of these suggestions (fighting, showing empathy, getting rid of ego) are meant to build trust with employees.

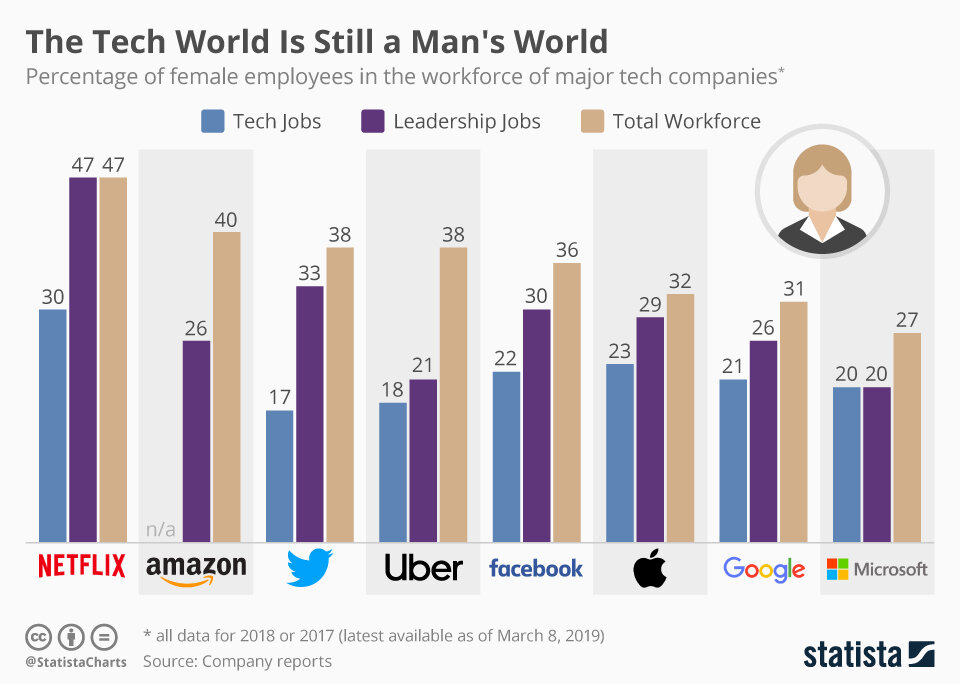

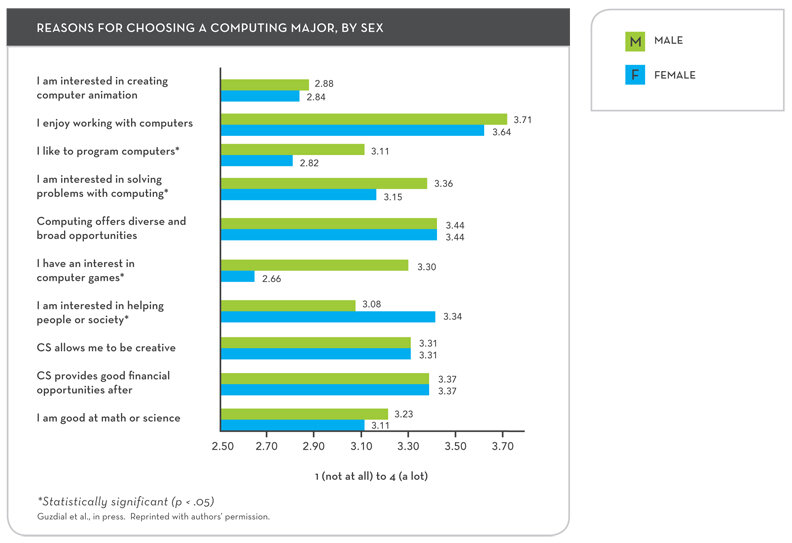

R-E-C-I-P-E for a Great Culture. The last fifth of the book is all focused on building culture at companies. It is the only topic Slootman stays on for more than a few chapters, so you know its important! RECIPE was an acronym created by the employees at Data Domain to describe the company’s values: Respect, Excellence, Customer, Integrity, Performance, Execution. Its interesting how simple and focused these values are. Technology has pushed its cultural delusion’s of grandeur to an extreme in recent years. The WeWork S-1 hilariously started with: “We are a community company committed to maximum global impact. Our mission is to elevate the world’s consciousness.” But none of Data Domain’s values were about changing the world to be a better place - they were about doing excellent, honest work for customers. Slootman is lasered focused on culture, and specifically views culture as an asset - calling it: “The only enduring, sustainable form of differentiation. These days, we don’t have a monopoly for very long on talent, technology, capital, or any other asset; the one thing that is unique to us is how we choose to come together as a group of people, day in and day out. How many organizations are there that make more than a halfhearted attempt at this?” Technology companies have taken different routes in establishing culture: Google and Facebook have tried to create culture by showering employees with unbelievable benefits, Netflix has focused on pure execution and transparency, and Microsoft has re-vamped its culture by adopting a Growth Mindset (has it really though?). Google originally promoted “Don’t be evil,” as part of its Code of Conduct but dropped the motto in 2018. Employees want to work for mission-driven organizations, but not all companies are really changing the world with their products, and Frank did not try to sugarcoat Data Domain’s data-duplication technology as a way to “elevate the world’s consciousness.” He created a culture driven by performance and execution - providing a useful product to businesses that needed it. The culture was so revered that post-acquisition, EMC instituted Data Domain’s performance management system. Data Domain employees were looked at strangely by longtime EMC executives, who had spent years in a big and stale company. Culture is a hard thing to replicate and a hard thing to change as we saw with the Innovator’s Dilemma. Might as well use it to help the company succeed!