This month we hear about Bill McDermott’s meteoric rise to the CEO job at SAP and his philosophy around management. I must also acknowledge the incredible and underappreciated role that Julie McDermott and Bill’s family plays in this book. Bill moved his family from NYC to Puerto Rico to Chicago to Rochester to Connecticut to California to Philadelphia over the course of his 25-year career. Sometimes with multiple moves rather quickly. The selflessness they displayed is unfathomable.

Tech Themes

Growing License Revenue at SAP. When Bill McDermott got to SAP North America, he quickly realized they were behind the game. The firm had enjoyed relatively unmatched success in its early years but was now coming into competition with one of Bill’s former employers - Siebel Systems. He saw what he viewed as lackluster standards - people were late to meetings, lacked professionalism, and moved painfully slowly on new action plans. McDermott created a new strategy around a $3B revenue target, and recruited the company’s top managers to share the plan in mini-meetings across every division. After providing the new strategy, he focused on value engineering, a way of demonstrating the ROI from implementing a company’s software. He instituted a weekly Top 20 Call, where the head of sales detailed the top 20 deals in progress, and Bill unleashed his sales intensity in helping people close deals. “What’s the business case? Have we presented it to the CEO? When is the next meeting? What, you just found out the company can’t sign because its purchasing director is on vacation? What’s your plan to backfill the loss? If someone didn’t know his next move, he wasn’t doing his job.” One of McDermott’s super-powers is maintaining a big vision while being able to slip into the micro-managing intensity of Andy Grove’s Only the Paranoid Survive and Ben Horowitz’s War-time CEO. 85% of C-Suite employees left, McDermott recruited 100 new sales employees, and in 2005, SAP America delivered $3.2B of revenue.

Reinvention. McDermott is unafraid to go in new directions and take on new challenges. He had earned his stripes by taking over challenged business units in Xerox, first Puerto Rico, then Chicago, and then Xerox Business Services, their outsourcing division. Xerox at the time was suffering from a classic Innovator’s Dilemma - the XBS division was growing quickly but resulted in lower profit margins, so was not getting the love and admiration it deserved. “Instead of worrying about the value of my retirement account, I was interested in growing the business. Rather than ignoring the changing market, we should have been pouncing on it…Many people thought I was crazy to join the junior varsity team. XBS represented only 5 percent of Xerox’s overall revenues. Others even tried to block my transfer to XBS.” McDermott believed in the power of pageantry and held a massive, blow-out sales conference in San Antonio, complete with fake politicians and news style interview booths. McDermott had set a $4B revenue target for XBS and he missed the target. XBS revenue’s grew from 900m of revenue to $2B in 1997, $2.7B in 1998, $3.4B in 1999, and $3.8B in 2000, just missing the $4B revenue target by 2000. “Was I upset that we fell shy of our $4B bull’s-eye? Not one bit. The point of setting audacious goals was that we could almost hit them and still accomplish something amazing. Had we never strived so high, we never would have hit as high as we did.”

Internet Bubble Comes Calling. Bill is human, like all of us, and so when the internet bubble started to take off, and he found himself on the sidelines managing an outsourcing business at struggling Xerox, he started to get the itch to get into the fray. A young startup called Techies.com had reached out asking if Bill would be their CEO. Bill considered it an interesting proposition - everything was going up and to the right and Techies could IPO as soon as next year. Techies.com was an online website for tech companies to post about job openings. After meeting everyone and interviewing for the job of CEO, Bill decides he can’t do it. “ The only thing about your company that really interests me is the money, and that’s the wrong reason to work for anyone.” Bill did get whisked away though, by another IT firm - Gartner. Bill had left Xerox for a whole 2 weeks in 1995 and joined Gartner at the urging of former Xerox executive, Follett Carter. McDermott joined Gartner in 2000, serving as President while Michael Fleisher served as CEO. He felt it was off from the first couple weeks on the job. “I saw it in the jeans and tieless shirts that even senior executives wore Mondays through Fridays. I felt it in Gartner’s small-company, New Economy culture, which shocked my corporate sensibilities.” Matters were maid worse when Julie McDermott was diagnosed with Breast Cancer. Things were tough for the year Bill was at Gartner, and he decided to move on to Siebel Systems where he worked with tech legend, Tom Siebel, founder of Siebel Systems and C3.AI. Bill would only last a year at Siebel too, burnt out after working tirelessly in the months following 9/11. In hindsight, each of these smaller steps into executive roles broadened Bill’s knowledge of the technology evolution and CRM space specifically. These would be the foundation for his job offer from SAP America in 2004.

Business Themes

Setting Ambitious Goals. Bill is no stranger to big roles and he absolutely relishes the spotlight. He has a smooth, calming, excited voice that shines through every word in the book. He is a big vision guy, but unafraid to get tactical in areas he knows well like sales. Having worked his way up from a rookie salesman at 22 to a district manager at Xerox, McDermott always took a similar approach to fixing broken organizations. When he got to his district manager role in Puerto Rico, the worst performing district in Xerox, he made it clear that things were going to change. He wanted to take Puerto Rico from the worst performing division to the best performing division in one year. He set out by asking the sales managers a simple question: “What do you need?” He slowly identified the issues holding the division back (a lack of investment, consistent expense cuts, and poor goal setting) and he fixed them. Puerto Rico became the number one sales group in Xerox. This extreme goal setting shows up multiple times in McDermott’s career. When he became head of Xerox’s outsourcing XBS division he set a $4B revenue goal. “Three billion dollars in revenue by 2000 was a more realistic goal yet still a dream target. So why not tell everyone $3B, Bill? Because my hurdle - getting my people ecstatic about selling outsourcing - was so high that I need to get everyone’s mind to a place where the dream soeemed so impossible that it was exciting to pursue. For more than a decade now, I’d watched teams rise to the expectations set for them. The more daring the target, the higher people rose.” When he got to SAP America, he proclaimed they’d be a $3B revenue business by 2005, after years of lackluster growth, “In the next three years, we are going to increase our revenue by one billion dollars. Since 1999, SAP America’s revenue had barely grown $100m, in total.” After a major operational overhaul, they achieved his goal. When he got to ServiceNow, he similarly announced a goal of $10B of annual revenue. Time will tell if he hits the goal.

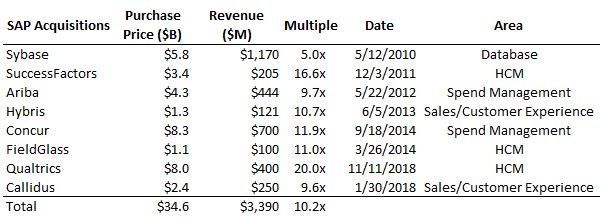

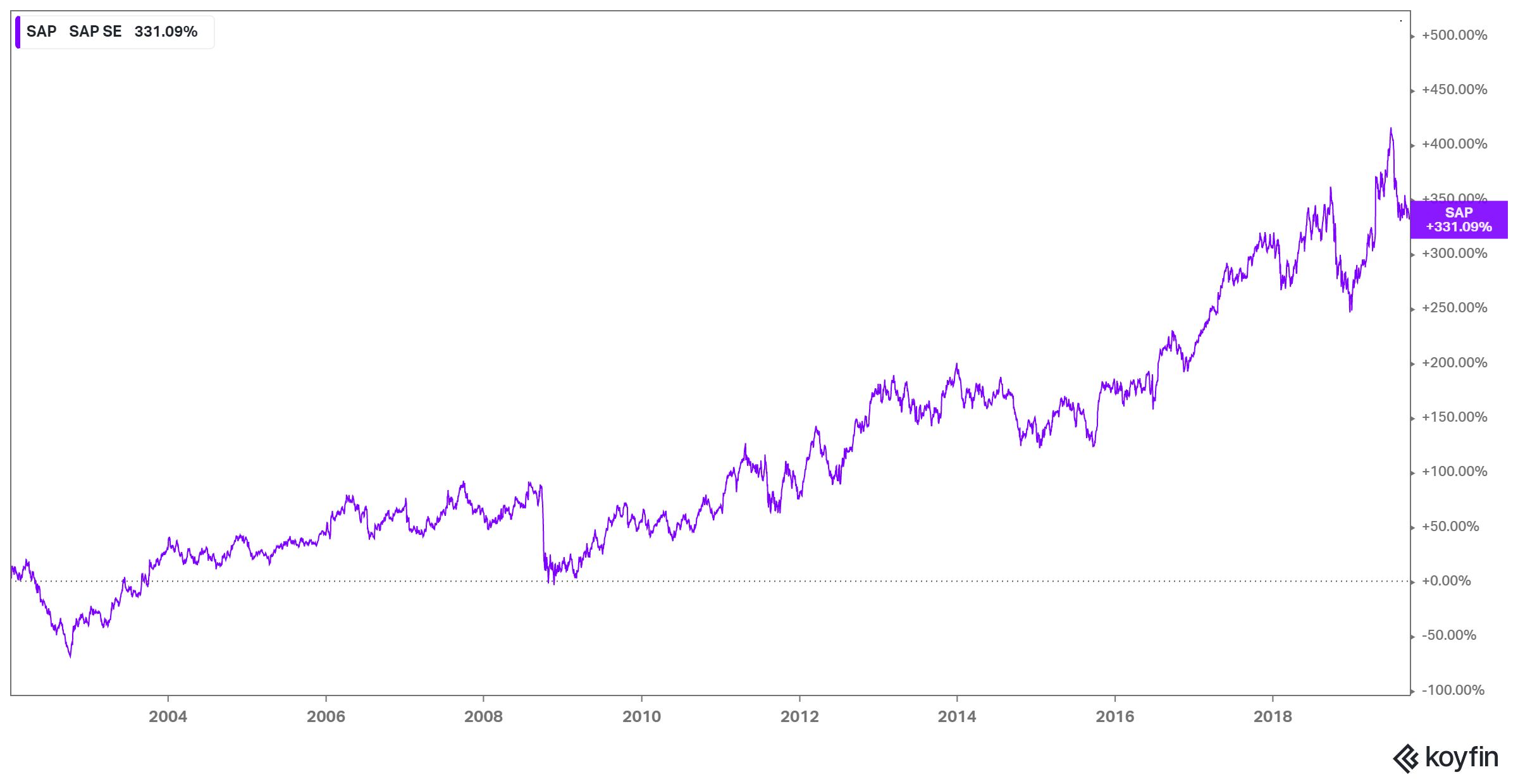

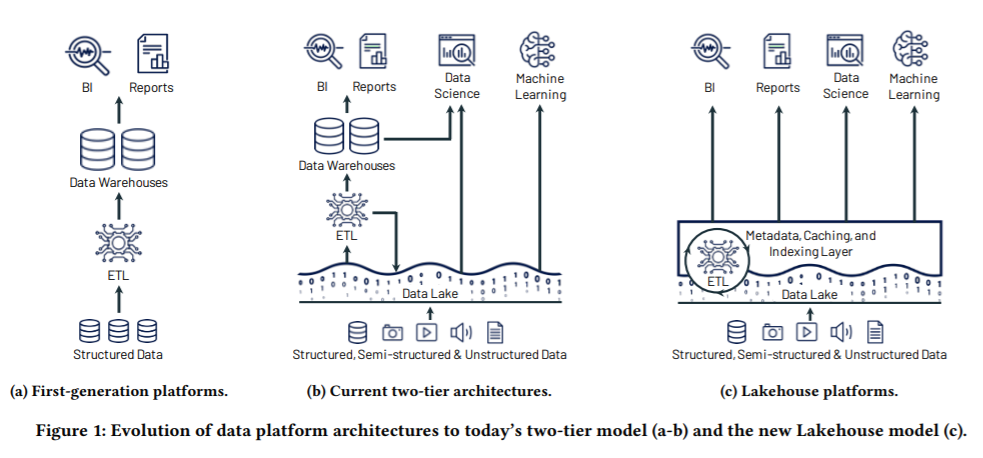

Big software M&A - Does it work? Bill McDermott was on the way to Hawaii when he got the call from SAP’s board about becoming Co-CEO of SAP. After the shock wore off, he quickly accepted the job, excited to lead the whole organization after he had successfully turned around SAP North America. Bill initially shared the CEO role with Jim Hagamann Snabe, a German engineer that would lead the product and engineering side of the business while Bill focused on commercial efforts. In 2014, Bill was named sole CEO, a new development for the traditional SAP that normally opted for a co-CEO model. Reflecting on it years later, Mcdermott commented in a Duke university visit in 2016, “Well, you know, when we were co-CEOs in 2010, it's what the company needed then. As you know, we were coming off the financial crisis of 2008. 2009 was a relatively slow recovery for the world, and SAP made a CEO change. And it was really important to have one office of the CEO with two friends, that really wanted to make a difference. And a lot of things needed to be done to build the company, build a strategy, do some major M&A moves, and get the company set up for growth again. And once that was done, then it became necessary to build on the vision but make much quicker decisions, move at a pace that was even beyond the pace we were moving at, which was pretty fast. And at that point, SAP needed that person that could make the call and be very, very decisive. And fortunately, things seem to be going pretty well.” McDermott launched an aggressive M&A campaign, spending $35B in acquisitions from 2010-2020. The acquisitions added about $3.4B of revenue to the company. These acquisitions were in all sorts of different areas but focused on SAP’s core areas including ERP, HCM, and Database technologies. I believe these acquisitions did two things simultaneously for SAP. Sirst it helped push a historically mainframe driven technology company into the cloud. Second, it broadened the capabilities of their core ERP offering while extending SAP into global markets, particularly strengthening its US position against ERP competitor Oracle, which had its own ERP and HCM applications. While these acquisitions worked for a time, the company is still fighting its license/maintenance past, and trying to move more aggressively to the cloud. The positive way to view these deals is Bill grew the organization, its capabilities, and its reach while using modest amounts of leverage and growing the company’s revenue and EPS. The negative way to view it is Bill went on a shopping spree of random technologies that were never fully integrated, and today saddle the company with enormous tech debt, little flexibility, and sub-par growth.

The Journey: Ithaca to CEO. Bill is a strong proponent of enjoying one’s career journey over its destination. As a night MBA student at Kellogg, he learned of the C.P Cavafy poem, Ithaca, which reads: “Keep Ithaka always in your mind. Arriving there is what you’re destined for. But don’t hurry the journey at all. Better if it lasts for years, so you’re old by the time you reach the island, wealthy with all you’ve gained on the way, not expecting Ithaka to make you rich. Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey. Without her you wouldn't have set out. She has nothing left to give you now. And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you. Wise as you will have become, so full of experience, you’ll have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.” As he contemplated moving on from Xerox, and pushing away his dream of becoming CEO, he came back to this poem, using it as a base before writing out his core beliefs and goals. “ My personal goals included having quality time with my family; to love Julie with the enthusiasm and compassion of our wedding day; to help my son (and eventually his sibling) grow into a healthy, happy, well-adjusted adult; to love my parents and my brother and sister, always remembering my roots, and to live with passion every day. Next, I listed my career aspirations: 1. To be a winner. 2. To lead others to the doorstep of their dreams. 3. To manage a career and not the other way around. 4. To never confuse that which is most important with that which is not. 5. To earn a living commensurate with my talent, but not be ruled by the shallow shadows of money. 6. To be the ruler of my own destiny, not to slave for what someone else wants my destiny to be - in control.” Ten years later, when he was considering moving on from Siebel Systems, Bill re-wrote his goals again and realized that he wanted to be in control of his own destiny. “ I wanted my freedom back. I was ready to be a CEO.”