This month we checked out an excellent book for founders, investors, and those interested in private company financings. The book hits on a lot of the key business and legal terms that aren’t discussed in typical startup books, making it useful no matter what stage of the entrepreneurial journey you are on.

Tech Themes

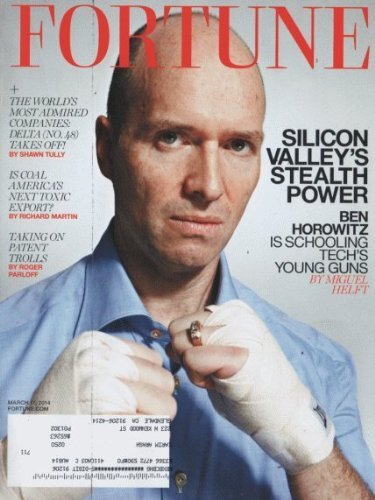

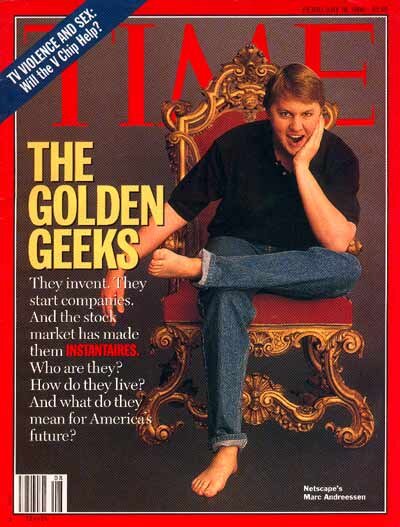

The Rise of Founder Friendly VC. Writing on his blog, Feld Thoughts, which was the original genesis for Venture Deals, Brad Feld mentioned that: “From 2010 forward, the entire VC market shifted into a mode that many describe as ‘founder friendly.’ Investor reputation mattered at both the angel and VC level.” In the 80’s and 90’s, because there was so little competition among venture capital firms, it was common for firms to dictate terms to company founders. The VC firms were the ones with the cash, and the founders didn’t have many options to choose from. If you wanted to build a big, profitable, public company, the only way to get there was by taking venture capital money. This trend started to unwind during the internet bubble, when founders started to maintain more and more of their businesses before the IPO. In fact, as this Harvard Business Review article points out, it was actually common to fire the founder/CEO prior to a public offering in favor of more seasoned leaders. This trend was bucked by Netscape, which eschewed traditional wisdom, going public less than a year from founding, with an unprofitable business. The Netscape IPO was clearly a royal coming-together of technology history. Tracing it all the way back - George Winthrop Fairchild started IBM in 1911; in the late 50’s, Arthur Rock convinced Fairchild’s son, Sherman to fund the traitorous eight (eight employees who left competitor Shockley Semiconductor) to start Fairchild Semiconductor; Eugene Kleiner (one of the traitorous eight) starts Kleiner Perkins, a venture capital firm that eventually invested in Netscape. Kleiner Perkins would also invest in Google (frequently regarded as one of the best and riskiest startup investments ever). Google was the first internet company to go public with a dual-class share structure where the founders would own a disproportionate amount of the voting rights of the company. Marc Andreessen, the founder of Netscape, loved this idea and eventually launched his own venture capital firm called Andreessen Horowitz, which ushered in a new generation of founder-friendly investing. At one point Andreessen was even quoted saying: “It is unsafe to go public today without a dual-class share structure.” Some notable companies with dual class shares include several Andreessen companies such as Facebook, Zynga, Box, and Lyft. Recently some have questioned whether founder friendly terms have pushed too far with some major flameouts from companies with the structure including Theranos, WeWork, and Uber.

How to Raise Money. Feld has several recommendations for fundraising that are important including having a target round size, demo, financial projections, and VC syndicate. Feld contends that CEOs who offer a range of varying round sizes to VC’s don’t really understand their business goals and use of proceeds. By having a concrete round size it shows that the CEO understands roughly how much money it will take to get to the next milestone or said another way, it shows the CEO understands the runway (in months) needed to build that new product or feature. It shows command of the financing and vision of the business. Feld encourages founders to provide a demo, because: “while never required, many investors respond to things we can play with, so even if you are an early stage company, a prototype or demo is desirable.” Beyond the explicit point here, the demo shows confidence in the product and at least some ability to sell, which is obviously a key aspect in eventually scaling the business. Another aspect of scaling the business is the financial model, but as Feld states, “the only thing that can be known about a pre-revenue company’s financial projections is that they are wrong.” While the numbers are meaningless for really early stage companies, for those that have a few customers it can be helpful to get a sense of long-term gross margins and aspects of the company you hope to invest in and / or change over time. Lastly, Feld gives advice for building a VC syndicate, or group of VC investors. Frequently lead investors will commit a certain dollar amount of the round, and it will be up to the founder/CEO to go find a way to build out the round. This can be incredibly challenging as detailed by Moz founder, Rand Fishkin, who thought he had a deal in hand only to see it be taken away. There are multiple bids in the VC fundraising process, one called an indication of interest, which is non-binding and normally provides a range on valuation, one called a letter of intent, which is slightly more detailed and may include legal terms of the deal such as board representation, liquidation preference, and governance terms, and then final legal documentation. A lot of time, the early bids can be withdrawn based off of poor market feedback or when a company misses its financial projections (like Moz did in its process). Understanding the process and the materials needed to complete the deal is helpful at setting expectations for founders.

Warrants, SPACs, and IPOs. With SPACMania in full-swing, we wanted to dive into SPACs and see how they work. We’ve discussed SPACs before, with regards to Chamath’s Social Capital merger with Virgin Galactic. But how do traditional SPAC financings work and why is there a rush of famous people, such as LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, to raise them? A SPAC or Specialty Purpose Acquisition Company is a blank-check company which goes public with the goal of acquiring a business, thereby taking it public. SPACs can be focused on industry or size of company and they are most frequently led by operational leaders and / or private equity firms. The reason SPACs have been gaining in popularity is that public markets investors are seeking more risk and a few high profile SPAC deals, namely DraftKings and Nikola, have traded better than expected. Most companies that are going public today are older, more mature businesses, and the public markets have been generally favorable to somewhat suspect ventures (Nikola is an electric truck company that has never produced a single truck, but is worth $14B on hype alone). VC firms and companies see the ability to get outsized returns on their investments because so many people are clamoring to find returns above the basically 0% offered by treasury bonds. The S&P 500 P/E ratio is now at around 26x compared to a historical average around 16x, meaning the market seems to be overvalued compared to prior times. SPACs typically come with an odd structure. A unit in a SPAC normally consists of one common share of stock and one warrant, which is the ability to purchase shares for $0.01 after a SPAC merges with its target company. The founders of the SPAC also receive founder shares, normally 20% of the business. Once the target is found, SPACs will often coordinate a PIPE (Private Investment in Public Equity), where a large private investor will invest mainly primary (cash to the balance sheet) capital into the business. This has emerged as a hip, new alternative to traditional IPOs, keeping with the theme of innovation in public offerings like direct listings, however, its unclear that this really benefits the company going public. Often the merged companies are the subject of substantial dilution by the SPAC sponsors and PIPE investors, lowering the overall equity piece management maintains. However, given the somewhat high valuations companies are receiving in the public markets (Zoom at 80x+ LTM Revenue, Shopify at 59x LTM Revenue), it may be worth the dilution.

Business Themes

How VC’s Make Money. In VC, the typical fund structure includes a general partnership (GP) and limited partners (LPs). The GP is the investors at the VC firm and the limited partners are the institutional investors that provide the money for the VC firm to invest. A typical structure involves the GP investing 1% of their own money (99% comes from LPs) and then getting paid an annual 2% management fee as well as 20% carried interest, or the profit made from investments. Using the example from the book: “Start with the $100 million fund. Assume that it's a successful fund and returns 3× the capital, or $300 million. In this case, the first $100 million goes back to the LPs, and the remaining profit, or $200 million, is split 80 percent to the LPs and 20 percent to the GPs. The VC firm gets $40 million in carried interest and the LPs get the remaining $160 million. And yes, in this case everyone is very happy.” Understanding how investors make money can help the entrepreneur better understand why VC’s pressure companies. As Feld points out, sometimes VC’s are trying to raise a new fund or have invested the majority of the fund already and thus do not care as much about some investments.

Growth at all costs. There has been a concerted focus in VC on the get big quick motto. Nobody better exemplifies this than Masayoshi Son and the $100B VC his firm Softbank raised a few years ago. With notable big bets on current losers like WeWork and Oyo, which are struggling during this pandemic, its unclear whether this motto remains true. Eric Paley, a Managing Partner at Founder Collective, expertly quantifies the potential downsides of a risk-it-all strategy: “Investors today have overstuffed venture funds, and lots of capital is sloshing around the startup ecosystem. As a result, young startups with strong teams, compelling products and limited traction can find themselves with tens of millions of dollars, but without much real validation of their businesses. We see venture investors eagerly investing $20 million into a promising company, valuing it at $100 million, even if the startup only has a few million in net revenue. Now the investors and the founders have to make a decision — what should determine the speed at which this hypothetical company, let’s call it “Fuego,” invests its treasure chest of money in the amazing opportunity that motivated the investors? The investors’ goal over the next roughly 24 months is for the company to become worth at least three times the post-money valuation — so $300 million would be the new target pre-money valuation for Fuego’s next financing. Imagine being a company with only a few million in sales, with a success hurdle for your next round of $300 million pre-money. Whether the startup’s model is working or not, the mantra becomes ‘go big or go home.’” This issue is key when negotiating term sheets with investors and understanding board dynamics. As Feld calls out: “The voting control issues in the early stage deals are only amplified as you wrestle with how to keep control of your board when each lead investor per round wants a board seat. Either you can increase your board size to seven, nine, or more people (which usually effectively kills a well-functioning board), or more likely the board will be dominated by investors.” As an entrepreneur, you need to be cognizant of the pressure VC firms will put on founders to grow at high rates, and this pressure is frequently applied by a board. Often late stage startups have 10 people+ on their board. UiPath, a private venture-backed startup that has raised over $1B and is valued at $10B, has 12 people on its board. With all of the different firms having their own goals, boards can become ineffective. Whenever startups are considering fundraising, it’s important to realize the person you are raising from will be an ongoing member of the company and voice on the board and will most likely push for growth.

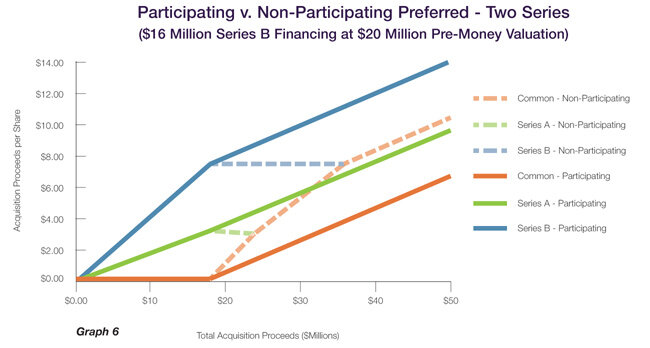

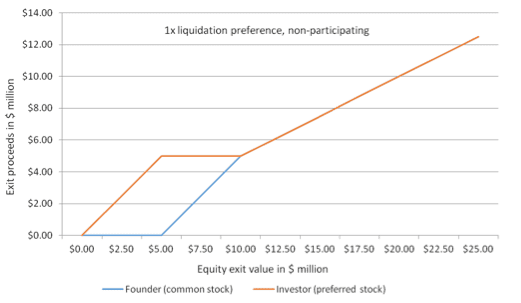

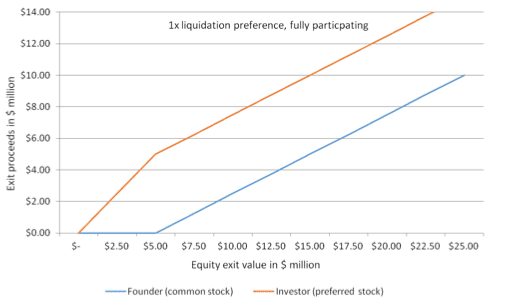

Liquidation Preference. One of the least talked about terms in venture capital among startup circles is liquidation preference. Feld describes liquidation preference as: “a certain multiple of the original investment per share is returned to the investor before the common stock receives any consideration.” Startup culture has tended to view fundraises as stamps of approval and success, but thats not always the case. As the book discusses, preference can lead to very negative outcomes for founders and employes. For example, let’s say a company at $10M in revenue raises $100 million with a 1x liquidation preference at a $400 million pre-money valuation ($500M post money). The company is pressured by its VCs to grow quickly but it has issues with product market fit and go to market; five years go by and the company is at $15M in revenue. At this point the VCs are not interested in funding any more, and the board decides to try to sell the company. A buyer offers $80 million and the board accepts it. At this point, all $80M has to go back to the original investors who had the 1x liquidation preference. All of the common stockholders and the founders, get nothing. Its not the desired outcome by any means, but its important to know. Some companies have not heeded this advice and continued to raise at massive valuations including Notion which has raised $10M at a $800 million valuation, despite being rumored to be around $15M in revenue. The company raised at a $1.6B valuation (an obvious 2x) after being rumored to be at $30M in revenue. While not taking dilution is nice as a founder, it also sets up a massive hurdle for the company and seriously cramps returns. A 3x return (which is low for VC investors) means selling the company for $4.8B, which is no small feat.