This month we dive into the birth of the biotech industry and learn about Genentech, a biotech company that was built on the back of novel recombinant DNA research in the 1970’s. The book covers most of the discovery and pre-IPO story of the company, weaving in commentary about political, social, and fundraising challenges the company faced.

Tech Themes

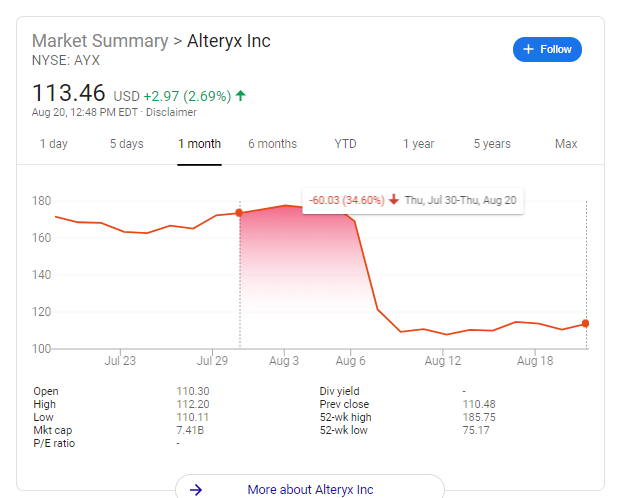

Education & Profits. The biotech industry creates an interesting symbiotic relationship between universities and businesses. Genentech was founded by an out-of-work venture capitalist named Bob Swanson and an exuberant scientific genius named Herb Boyer. In 1973, Boyer and a colleague, Stan Cohen, had conceived of the idea of using restriction enzymes to cleave DNA fragments, allowing the scientists to insert and express almost any gene in bacteria. In 1977-78, Boyer, Riggs, and Itakura showed that the recombinant DNA process could create somatostatin and insulin. Because of the unbelievable economic potential of their findings, Stanford (where Cohen worked) and UCSF (where Boyer worked) decided to file a patent on the recombinant DNA procedure. The patent process sparked a massive debate about the commercialized use of their procedure, with several scientists, like National Academy of Science Chairman Paul Berg, calling for an investigation and formal rules. As Hughes notes, “The 1970s was notably inhospitable to professors forming consuming relationships with business, let alone taking the almost unheard-of step of founding a company without giving up a professorship.” This challenge of balance incentives: helping society, contributing all biological research back to the world for free, and personal financial and celebrity gain is hard. Many of the world’s leading researchers are motivated not only by deep investigative science but also by the notoriety of being published in the world’s leading journals. Today, several of the world’s leading AI researchers face a similar dilemma. In 2012, Geoff Hinton, a former Unversity of Toronto professor, auctioned off his AI algorithm and job between Google, Baidu, and Microsoft for a one-time £30M payout. Databricks, a big data company, recently raised money at a $38B valuation - their CEO, Ali Ghodsi, conceived of the idea for Databricks as a Ph.D. student at UC Berkeley, where he remains an adjunct professor. The twisted and complicated world of Academia and corporations continues!

IP. One of the big challenges of Genentech’s unique academic heritage was a massive intellectual property battle that would last for years. In 1976, Bob Swanson set out to negotiate an exclusive license to the Boyer-Cohen patent from Stanford and UCSF. He was rebuffed by the administration, trying to avoid the politically heated topic of recombinant DNA research. Things were made even more complicated in 1978. On New Year’s eve at 12:00 am, soon-to-be new employees Peter Seeburg and Axel Ulrich broke into their former UCSF lab to take research specimens related to contract research work they were performing for Genentech. In 1999, after years of patent disputes, Genentech finally settled the patent infringement for $200M, one of the largest biotech settlements ever. With such enormous sums of money at stake, the question of who owns the invention and how that invention is used is hotly debated and contested - pharmaceutical companies have seen larger and larger misuse settlements.

Regulation & Action. An often forgotten aspect of commercial industry change is regulation, perhaps because it is complicated and slow to develop, but the effects can be enormous. iN 1983, in reaction to chronic under-investment in drugs serving small patient population sizes (“Rare Disease”), the Department of Health and Human Services and FDA helped enact the Orphan Drug act of 1983. “That law, the Orphan Drug Act, provided financial incentives to attract industry’s interest through a seven-year period of market exclusivity for a drug approved to treat an orphan disease, even if it were not under patent, and tax credits of up to 50 percent for research and development expenses. In addition, FDA was authorized to designate drugs and biologics for orphan status (the first step to getting orphan development incentives), provide grants for clinical testing of orphan products, and offer assistance in how to frame protocols for investigations.” A further revision to the Act in 2002 specified a rare disease as a disease affecting a patient population of <200,000 people. Coupled with these amazing incentives was the ability to price drugs in response to the exclusivity received for performing the research that led to the drug’s discovery. Such exclusivity has led to much higher prices for rare disease drugs, causing anger from patients (and insurance groups) who need to pay for these effective but high-priced drugs. Some economists have even studied the idea of “fairness” in orphan drug pricing - considering whether a rare disease drug that cures 90% of patients with the disease should be priced significantly higher than those that cure a smaller percentage of the population. These incentives have produced a massive influx of investment into the space, with 838 total orphan drug indications and 564 distinct drugs created to help patients with rare diseases.

Business Themes

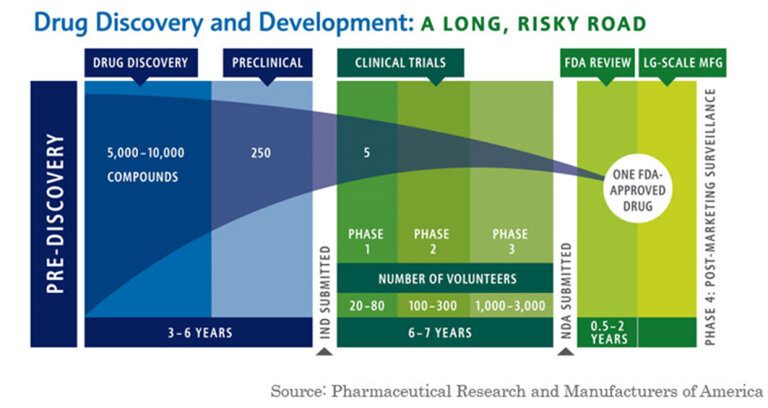

Partnerships. The biotech industry thrives off of partnerships. This is primarily due to the enormous cost of bringing a drug to market, with a recent paper pinning the number for just R&D costs at greater than ~$1B. Beyond the cost of FDA Phase 1, 2, and 3 trials - $4M, $13M, and $20M median - companies often have to deal with many failures and re-directions along the way. On top of that, companies have to manufacture, sell, and market the drug to patient populations and physicians. Genentech was one of the first companies to establish partnerships with major pharmaceuticals companies. Genentech considered many different partnerships for different parts of its drug pipeline (something that is still done today). In August of 1978, Genentech partnered with Kabi, a Swedish pharmaceutical manufacturer, to produce human growth hormone using the Genentech approach. The deal included a $1M upfront payment for exclusive foreign marketing rights. Three weeks later, Genentech partnered with Eli Lilly to start making human insulin using the recombinant DNA approach - the deal was a twenty-year R&D contract with an upfront fee of $500,000 for exclusive worldwide rights to insulin; Genentech received 6% royalties and City of Hope (an education institution) received 2% of product sales. In January of 1980, Genentech signed a deal with Hoffman-La Roche to collaborate on leukocyte and fibroblast interferon - a chemical that was believed to be a potential cancer panacea. All of these deals were new back then but are now commonplace today - with marketing, R&D, and royalty partnerships the norm in the biotech and pharmaceuticals industry.

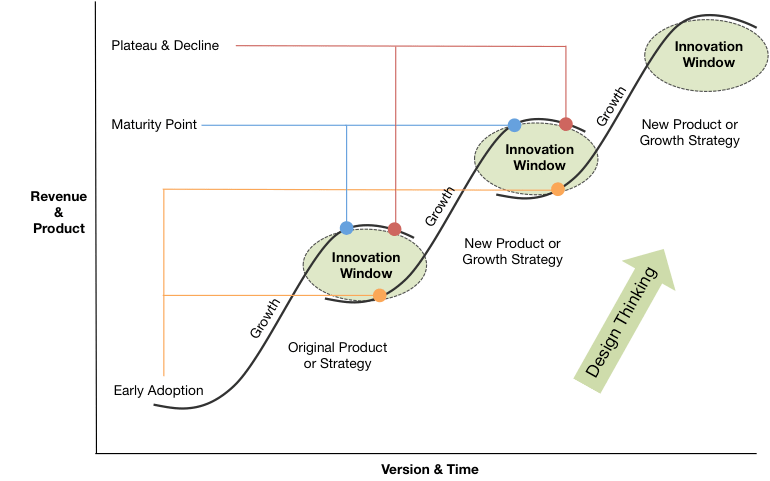

The Perils and Beauty R&D. Pharmaceutical and Biotech companies face a very difficult challenge in bringing a drug to market. Beyond the costs detailed above, the success rate is so low that companies often need to have multiple scientific projects going on at once. The book details this challenge: “By the second quarter of 1979, the company had four new projects underway, all but one sponsored by a major corporation: Hoffman-La Roche on interferon; Monsanto on animal growth hormone; Institut Merieux on hepatitis B vaccine; and a Genentech fund project on the hormone thymosin.” This was all in addition to its Kabi and Eli Lilly deals! This brings up the idea of S curves, whereby product adoption reaches a peak and new products pick up to continue the growth of the organization. This is common in all businesses and markets but especially difficult to predict in biotech and pharma where drug development takes years, patents come and go, and new drug success is probabilistically low. This is the double-sided challenge of big pharma, where companies debate internal R&D spending or external M&A to drive new growth vectors on a company’s S-Cuve. It’s something that Genetech is still trying to figure out today.

A Silicon Valley Story. While the center of the biotech industry today is arguably Cambridge, MA, Genentech was an original Silicon Valley - high risk/high reward bet. Genentech was funded by the historically great Kleiner Perkins - a silicon valley VC born out of the semiconductor company Fairchild Semiconductor (where Kleiner was part of the traitorous eight). Kleiner was joined by Tom Perkins, who worked at Hewlett Packard in the 1960s, and brought HP into the minicomputer business. As one of the earliest venture capitalists, with a great knowledge of the Silicon Valley semiconductor and technological innovation boom, they hit big winners with Compaq, EA, Amazon, Sun Microsystems, and many others. A lot of these investments were speculative at the time and the team understood more risk at the earlier stages meant more reward down the line. As Perkins put it: “Kleiner & Perkins realizes that an investment in Genentech is highly speculative, but we are in the business of making highly speculative investments.” After weeks of meeting with Swanson and a key meeting with Herb Boyer, Perkins took the plunge, leading a $100,000 seed investment in Genentech in May of 1976. Perkins commented: “I concluded that the experiment might not work, but at least they knew how to do the experiment.” Despite the work of raising billions of dollars for Genentech’s continually growing product and partnership pipeline, Perkins commented years later on his involvement with Genentech: “I can’t remember at what point it dawned on me that Gentech would probably be the most important deal of my life, in many terms - the returns, the social benefits, the excitement, the technical prowess, and the fun.” Perkins stayed on the board for 20 years and Kleiner Perkins led several investments in the company over the years. Genentech eventually got acquired by Hoffman-La Roche (now called Roche), when they bought 60% of the company for $2B in 1990 and the rest of the company for $47B in 2009. Genentech was the first big biotech win and helped establish Silicon Valley’s cache in the process!