This month we take a look at a classic high-tech growth marketing book. Originally published in 1991, Crossing the Chasm became a beloved book within the tech industry although its glory seems to have faded over the years. While the book is often overly prescriptive in its suggestions, it provides several useful frameworks to address growth challenges primarily early on in a company’s history.

Tech Themes

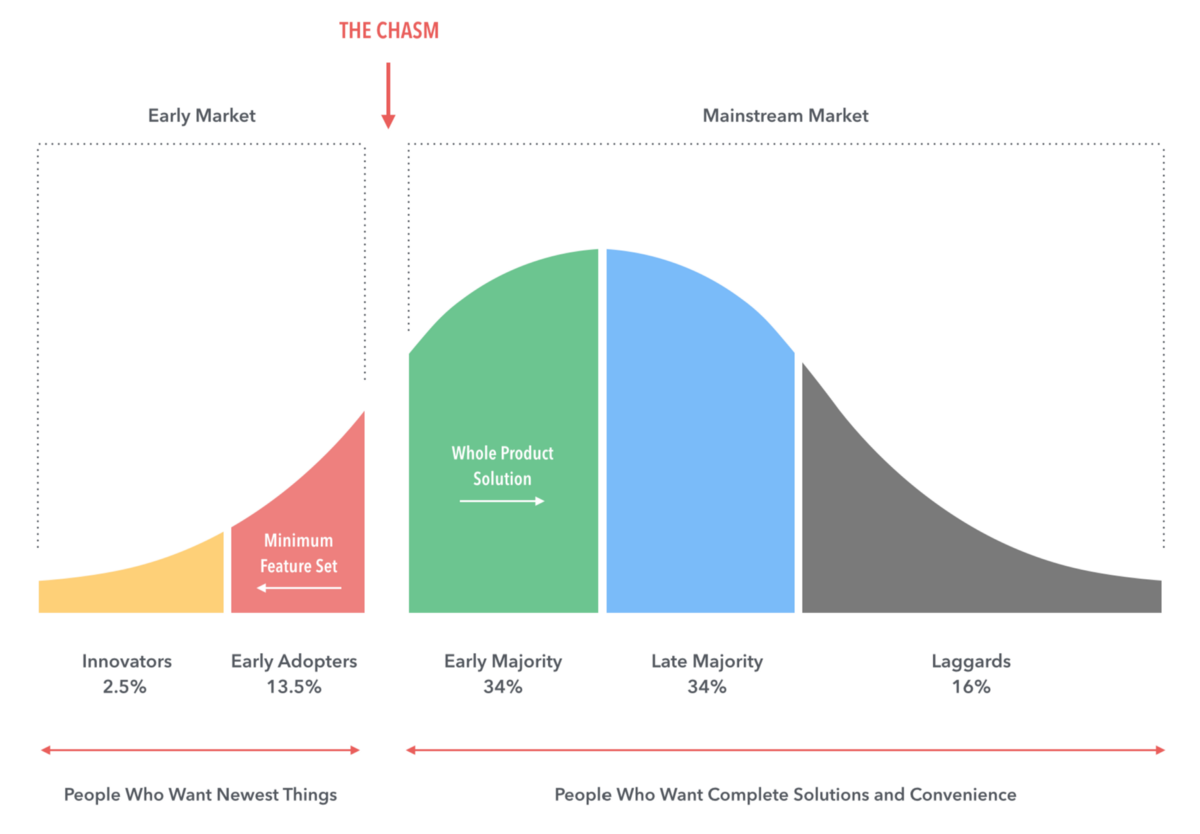

Technology Adoption Life Cycle. The core framework of the book discusses the evolution of new technology adoption. It was an interesting micro-view of the broader phenomena described in Carlota Perez’s Technological Revolutions. In Moore’s Chasm-crossing world, there are five personas that dominate adoption: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards. Innovators are technologists, happy to accept more challenging user experiences to push the boundaries of their capabilities and knowledge. Early adopters are intuitive buyers that enjoy trying new technologies but want a slightly better experience. The early majority are “wait and see” folks that want others to battle test the technology before trying it out, but don’t typically wait too long before buying. The late majority want significant reference material and usage before buying a product. Laggards simply don’t want anything to do with new technology. It is interesting to think of this adoption pattern in concert with big technology migrations of the past twenty years including: mainframes to on-premise servers to cloud computing, home phones to cell phones to iphone/android, radio to CDs to downloadable music to Spotify, and cash to check to credit/debit to mobile payments. Each of these massive migration patterns feels very aligned with this adoption model. Everyone knows someone ready to apply the latest tech, and someone who doesn’t want anything to do with it (Warren Buffett!).

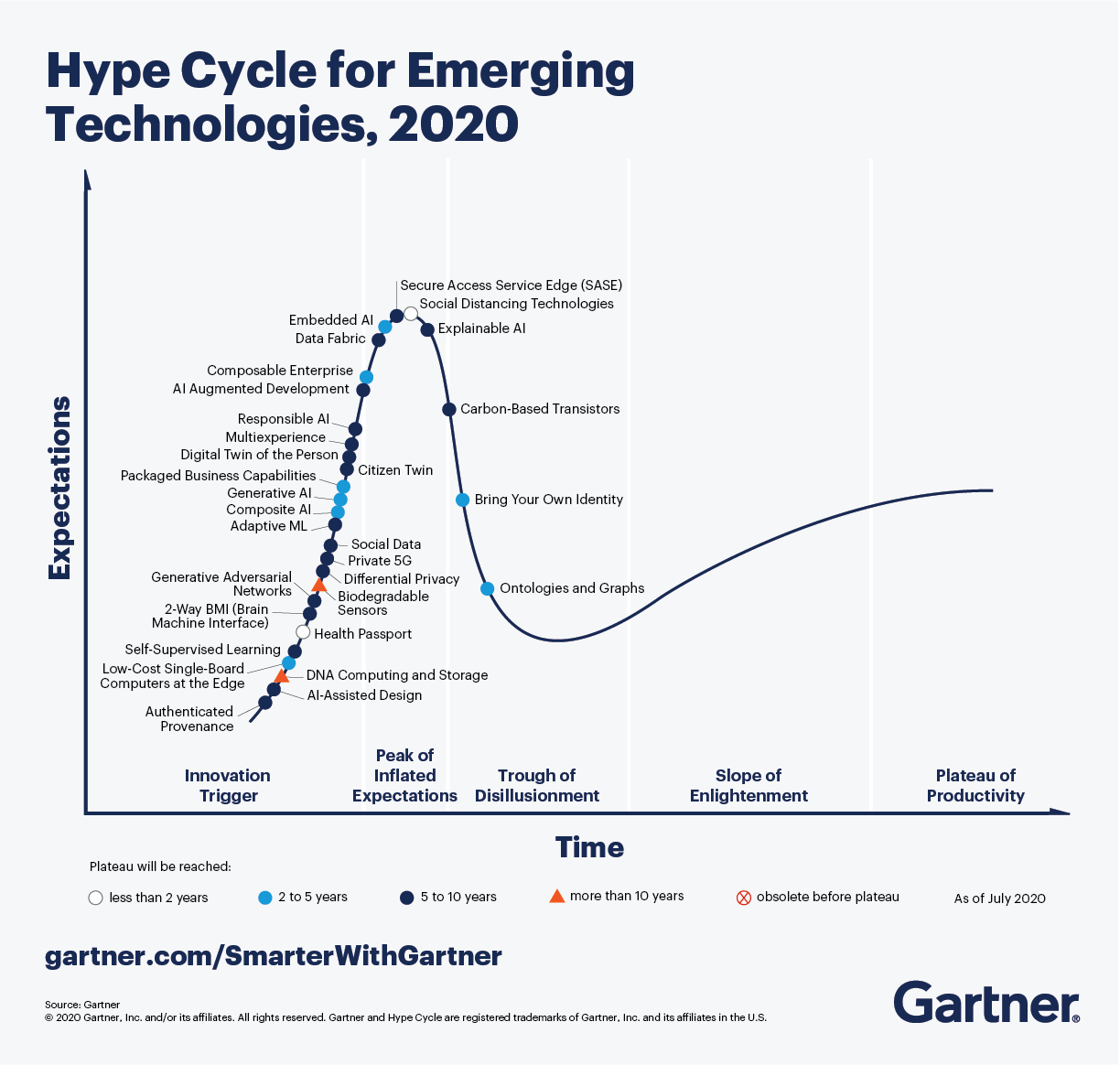

Crossing the Chasm. If we accept the above as a general way products are adopted by society (obviously its much more of a mish/mash in reality), we can posit that the most important step is from the early adopters to the early majority - the spot where the bell curve (shown below) really opens up. This is what Geoffrey Moore calls Crossing the Chasm. This idea is highly reminiscent of Clay Christensen’s “not good enough” disruption pattern and Gartner’s technology hype cycle. The examples Moore uses (in 1991) are also striking: Neural networking software and desktop video conferencing. Moore lamented: “With each of these exciting, functional technologies it has been possible to establish a working system and to get innovators to adopt it. But it has not as yet been possible to carry that success over to the early adopters.” Both of these technologies have clearly crossed into the mainstream with Google’s TensorFlow machine learning library and video conferencing tools like Zoom that make it super easy to speak with anyone over video instantly. So what was the great unlock for these technologies, that made these commercially viable and successfully adopted products? Well since 1990 there have been major changes in several important underlying technologies - computer storage and data processing capabilities are almost limitless with cloud computing, network bandwidth has grown exponentially and costs have dropped, and software has greatly improved the ability to make great user experiences for customers. This is a version of not-good-enough technologies that have benefited substantially from changes in underlying inputs. The systems you could deploy in 1990 just could not have been comparable to what you can deploy today. The real question is - are there different types of adoption curves for differently technologies and do they really follow a normal distribution as Moore shows here?

Making Markets & Product Alternatives. Moore positions the book as if you were a marketing executive at a high-tech company and offers several exercises to help you identify a target market, customer, and use case. Chapter six, “Define the Battle” covers the best way to position a product within a target market. For early markets, competition comes from non-consumption, and the company has to offer a “Whole Product” that enables the user to actually derive benefit from the product. Thus, Moore recommends targeting innovators and early adopters who are technologist visionaries able to see the benefit of the product. This also mirrors Clayton Christensen’s commoditization de-commoditization framework, where new market products must offer all of the core components to a system combined into one solution; over time the axis of commoditization shifts toward the underlying components as companies differentiate by using faster and better sub-components. Positioning in these market scenarios should be focused on the contrast between your product and legacy ways of performing the task (use our software instead of pen and paper as an example). In mainstream markets, companies should position their products within the established buying criteria developed by pragmatist buyers. A market alternative serves as the incumbent, well-known provider and a product alternative is a near upstart competitor that you are clearly beating. What’s odd here is that you are constantly referring to your competitors as alternatives to your product, which seems counter-intuitive but obviously, enterprise buyers have alternatives they are considering and you need to make the case that your solution is the best. Choosing a market alternative lets you procure a budget previously used for a similar solution, and the product alternative can help differentiate your technology relative to other upstarts. Moore’s simple positioning formula has helped hundreds of companies establish their go-to-market message: “For (target customers—beachhead segment only) • Who are dissatisfied with (the current market alternative) • Our product is a (new product category) • That provides (key problem-solving capability). • Unlike (the product alternative), • We have assembled (key whole product features for your specific application).”

Business Themes

What happened to these examples? Moore offers a number of examples of Crossing the Chasm, but what actually happened to these companies after this book was written? Clarify Software was bought in October 1999 by Nortel for $2.1B (a 16x revenue multiple) and then divested by Nortel to Amdocs in October 2001 for $200M - an epic disaster of capital allocation. Documentum was acquired by EMC in 2003 for $1.7B in stock and was later sold to OpenText in 2017 for $1.6B. 3Com Palm Pilot was a mess of acquisitions/divestitures. Palm was acquired by U.S Robotics which was acquired by 3COM in 1997 and then subsequently spun out in a 2000 IPO which saw a 94% drop. Palm stopped making PDA devices in 2008 and in 2010, HP acquired Palm for $1.2B in cash. Smartcard maker Gemplus merged with competitor Axalto in an 1.8Bn euro deal in 2005, creating Gemalto, which was later acquired by Thales in 2019 for $8.4Bn. So my three questions are: Did these companies really cross the chasm or were they just readily available success stories of their time? Do you need to be the company that leads the chasm crossing or can someone else do it to your benefit? What is the next step in the chasm journey after its crossed and why did so many of these companies fail after a time?

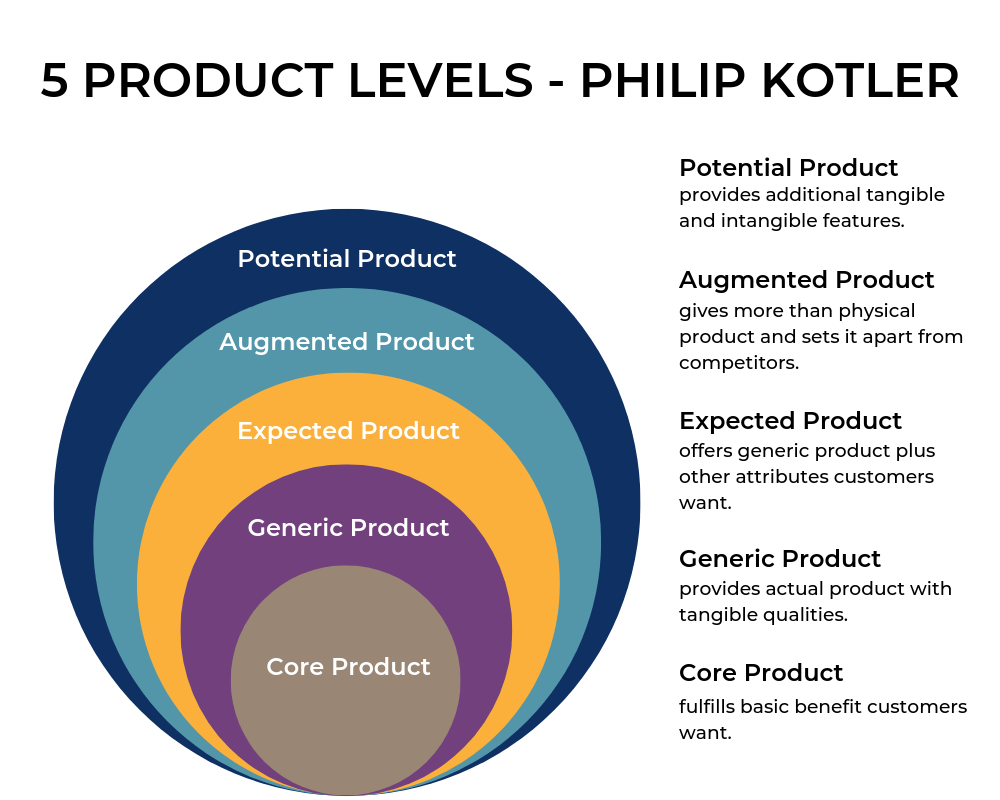

Whole Products. Moore leans into an idea called the Whole Product Concept which was popularized by Theodore Levitt’s 1983 book The Marketing Imagination and Bill Davidow’s (of early VC Mohr Davidow) 1986 book Marketing High Technology. Moore explains the idea: “The concept is very straightforward: There is a gap between the marketing promise made to the customer—the compelling value proposition—and the ability of the shipped product to fulfill that promise. For that gap to be overcome, the product must be augmented by a variety of services and ancillary products to become the whole product.” There are four different perceptions of the product: “1. Generic product: This is what is shipped in the box and what is covered by the purchasing contract. 2.Expected product: This is the product that the consumer thought she was buying when she bought the generic product. It is the minimum configuration of products and services necessary to have any chance of achieving the buying objective. For example, people who are buying personal computers for the first time expect to get a monitor with their purchase-how else could you use the computer?—but in fact, in most cases, it is not part of the generic product. 3.Augmented product: This is the product fleshed out to provide the maximum chance of achieving the buying objective. In the case of a personal computer, this would include a variety of products, such as software, a hard disk drive, and a printer, as well as a variety of services, such as a customer hotline, advanced training, and readily accessible service centers. 4. Potential product: This represents the product’s room for growth as more and more ancillary products come on the market and as customer-specific enhancements to the system are made. These are the product features that have maybe expected or additional to drive adoption.” Moore makes a subtle point that after a while, investments in the generic/out-of-the-box product functionality drive less and less purchase behavior, in tandem with broader market adoption. Customers want to be wooed by the latest technology and as products become similar, customers care less about what’s in the product today, and more about what’s coming. Moore emphasizes Whole Product Planning where you can see how you get to those additional features into the product over time - but Moore was also operating in an era when product decisions and development processes were on two-year+ timelines and not in the DevOps era of today, where product updates are pushed daily in some cases. In the bottoms-up/DevOps era, its become clear that finding your niche users, driving strong adoption from them, and integrating feature ideas from them as soon as possible can yield a big success.

Distribution Channels. Moore focuses on each of the potential ways a company can distribute its solutions: Direct Sales, two-tier retail, one-tier retail, internet retail, two-tier value-added reselling, national roll-ups, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and system integrators. As Moore puts it, “The number-one corporate objective, when crossing the chasm, is to secure a channel into the mainstream market with which the pragmatist customer will be comfortable.” These distribution types are clearly relics of technology distribution in the early 1990s. Great direct sales have produced some of the best and biggest technology companies of yesterday including IBM, Oracle, CA Technologies, SAP, and HP. What’s so fascinating about this framework is that you just need one channel to reach the pragmatist customer and in the last 10 years, that channel has become the internet for many technology products. Moore even recognizes that direct sales had produced poor customer alignment: “First, wherever vendors have been able to achieve lock-in with customers through proprietary technology, there has been the temptation to exploit the relationship through unfairly expensive maintenance agreements [Oracle did this big time] topped by charging for some new releases as if they were new products. This was one of the main forces behind the open systems rebellion that undermined so many vendors’ account control—which, in turn, decrease predictability of revenues, putting the system further in jeopardy.” So what is the strategy used by popular open-source bottoms up go-to-market motions at companies like Github, Hashicorp, Redis, Confluent and others? Its straightforward - the internet and simple APIs (normally on Github) provide the fastest channel to reach the developer end market while they are coding. When you look at Open Source scaling, it can take years and years to Cross the Chasm because most of these early open source adopters are technology innovators, however, eventually, solutions permeate into massive enterprises and make the jump. With these new go-to-market motions coming on board, driven by the internet, we’ve seen large companies grow from primarily inbound marketing tactics and less direct outbound sales. The companies named above as well as Shopify, Twilio, Monday.com and others have done a great job growing to a massive scale on the backs of their products (product-led growth) instead of a salesforce. What’s important to realize is that distribution is an abstract term and no single motion or strategy is right for every company. The next distribution channel will surprise everyone!

Dig Deeper

How the sales team behind Monday is changing the way workplaces collaborate

Frank Slootman (Snowflake) and Geoffrey Moore Discuss Disruptive Innovations and the Future of Tech

Growth, Sales, and a New Era of B2B by Martin Casado (GP at Andreessen Horowitz)

Strata 2014: Geoffrey Moore, "Crossing the Chasm: What's New, What's Not"