This month we cover our third Frank Slootman book, Amp it Up! It covers Slootman’s overall philosophy with a specific focus on achieving significant growth at scale and how companies can push the boundary of their growth potential. Frank only wrote the book because Snowflake’s CMO encouraged him to do so.

Tech Themes

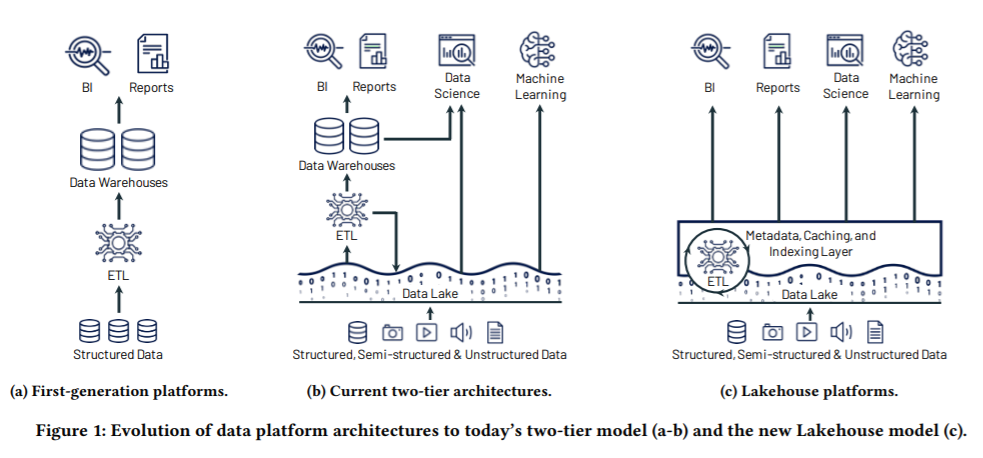

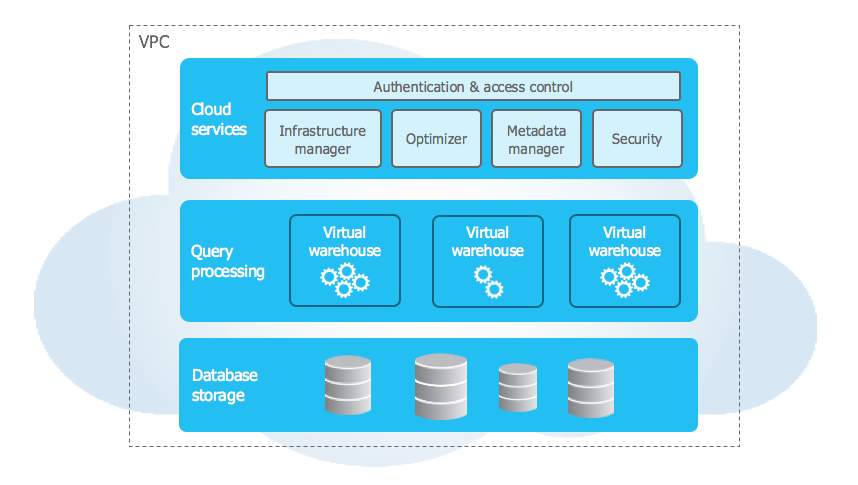

Expanding the TAM. One core idea that Slootman has used across both ServiceNow and Snowflake is the idea of expanding the TAM. By expanding the TAM, you lengthen your growth runway because there are more people who are capable of using your software. Slootman employed this strategy perfectly at ServiceNow. When on the IPO roadshow for the company, analysts at Gartner kept telling potential investors that ServiceNow had a small TAM of only $1.5B. An old short report of ServiceNow by Kerrisdale Capital highlights this confusion: “ The overall ITSM market size is only $1.5 billion, less than one-third of NOW's $4.7 billion market capitalization. Leading technology research firm Gartner estimates that the IT Service Management market opportunity is $1.5 billion, and is growing at a modest 7% per year. Furthermore, Gartner's research predicts that only 50% of IT organizations will move to SaaS by 2015, implying that the total market opportunity for NOW's ITSM business is less than $1 billion. Given emerging competition from other SaaS ITSM service providers, we believe that the company will have a difficult time exceeding 30% market share. At $207m of LTM revenue, NOW appears to already control 10% to 15% of the market. So even if NOW's market share rises to 30%, which we don't see happening until 2014 at the earliest, NOW's ITSM business should be generating less than $600m in revenue with limited additional growth opportunities. The result of the limited market size and increasing competition will be flattening growth over the next few years.” Kerrisdale was clearly incorrect. Market size estimates are now closer to $12-15B. Slootman and the team realized that to complete the full remediation of issues, more people in the organization needed to access ServiceNow’s tools and core ticketing system. They deliberately went function by function (network engineers, sys admins, database admins) and added specific functionality to enhance the user experience of these groups. One of these product enhancements was ServiceNow’s configuration management database or CMDB, which keeps a log of every device and its exact specifications to allow for faster triage of issues. Slootman has taken this approach to Snowflake, which started out by focusing on just the data warehousing workload but has since expanded into seven unique workloads: data warehouse, data engineering, data science, collaboration, data sharing, unistore, and cybersecurity. These workloads now bring in more people to the Snowflake platform: database administrators, data engineers, analytics engineers, data analysts, data scientists, and cybersecurity analysts. Each new set of tools added, enhances the overall value of the platform and the stickiness of the solution within the organization. This is a great roadmap for how to keep growth elevated in horizontal markets.

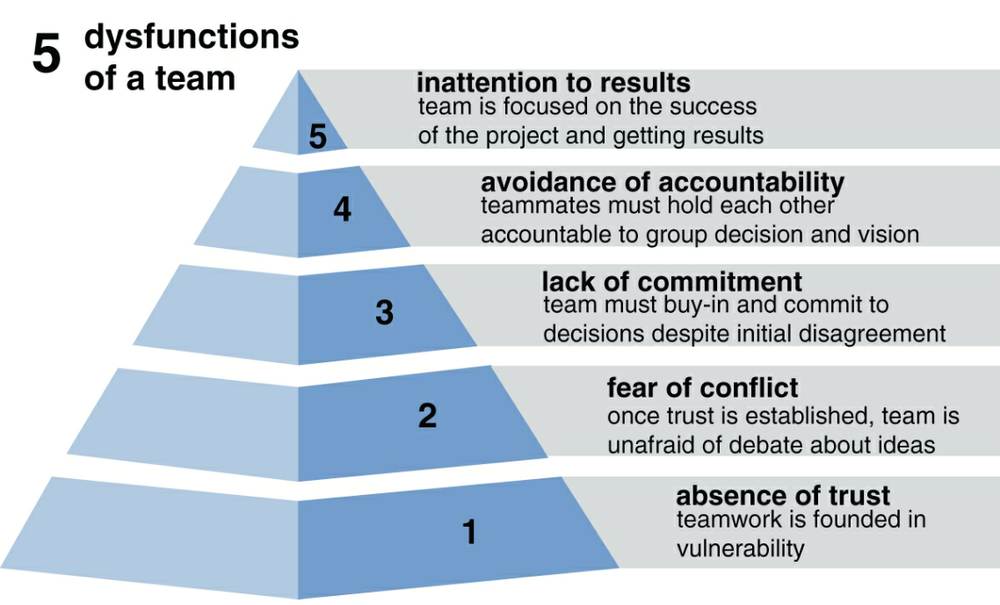

Strategy vs. Execution. “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.” Peter Drucker, a famous consultant, and author of the Concept of the Corporation, believed that culture was far more important than strategy. Slootman agrees and even takes it one step further: “Execution has to be your number one goal. Strategy can’t be mastered until you can execute. Great execution is rarer than great strategy.” Slootman actually disagrees with Drucker on the management by objectives framework, “Another source of misalignment is management by objectives, which I have eliminated at every company i’ve joined in the last twenty years. MBOs cause employees to act as if they are running their own show, because they get compensated on their personal metrics, it is next to impossible to pull them off projects. They will be negotiating with you for relief. That is not alignment, that is every man for himself. If you need MBOs to get people to do their jobs, you may have the wrong people, the wrong managers, or both.” In Slootman’s eyes, management by objectives, which sets objectives for an entire organization that are translated into individual goals, ends up being abused by managers. Managers may rely on the objectives solely, and discount the leadership and creative thought necessary to succeed beyond an objective. “A person can do an excellent job according to objective measurement standards, but can fail miserably as a partner, subordinate, superior, or colleague. It is common for people not to be promoted for personal reasons than because of technical inadequacies.” For Slootman, superior execution comes from good judgment, and good judgment comes from bad judgment. Bad judgment is only made clear through experience, which can be the best teacher in his eyes. “New managers have to learn from and through their management chain. Organizations cannot scale and mature around inexperienced management staff.” At Data Domain, Slootman’s team finally started seeing success when they found the right leader for their contract manufacturing organization; at ServiceNow, when they found the right leader for cloud infrastructure; at Snowflake, when they found the right leader for scaling. “The organization needs innovation and discipline, or else the place will simply implode on itself. The common mistake is to rely on our innovators for discipline.” 5 dysfunctions of a team. Why execution is harder than strategy. But need to Prepare your next strategy early so you are ready when you get there.

Recruiting Talent. Slootman urges leaders to recruit drivers, not passengers. “Passengers are people who don't mind simply being carried along by the company's momentum, offering little or no input, seemingly not caring much about the direction chosen by management. They are often pleasant, get along with everyone, attend meetings promptly, and generally do not stand out as troublemakers. They are often accepted into the fabric of the organization and stay there for many years. The problem is that while passengers can often diagnose and articulate a problem quite well, they have no investment in solving it. They don't do the heavy lifting. Drivers, on the other hand, get their satisfaction from making things happen, not blending in with the furniture. They feel a strong sense of ownership for their projects and teams and demand high standards from both themselves and others. They exude energy, urgency, ambition, even boldness. Faced with a challenge, they usually say, ‘Why not’ rather than ‘That’s impossible.’ These qualities make drivers massively valuable. Finding, recruiting, rewarding, and retaining them should be among your top priorities.” What I find most interesting about this philosophy is that most jobs train people to be passengers. Most CEOs prefer the calm and non-trouble making attitude of passengers over the outspokenness and aggression that sometimes comes with drivers. So what do you do when you find passengers? Its simple - get them off the bus. Although it can be intense, you need to execute by removing people first, getting the right people in, and then getting the right people in the right spots. We talked about this analogy in the Jim Collins book Good to Great. “At a struggling company, you need to change things fast by switching out people whose skills no longer fit the mission or never really did in the first place. The other advantage of moving fast is that everyone who stays on the bus will know that you are dead serious about high standards. The good ones will be energized by those standards.” The challenge with moving quickly is finding the right balance for what the organization can absorb at any given time. Moving too quickly when the organization is not ready, or moving too quickly when the plan hasn’t been set can lead to drastic consequences.

Business Themes

Turnarounds as a Training Ground. Famous football coach Bill Walsh joined the San Francisco 49ers after they were the last placed team in the NFL with a 2-14 record. The next season, Walsh’s first, the 49ers repeated the performance - 2-14 again. Walsh at one point broke down on a flight home from a crushing defeat against Miami. 16 months later, he was Super Bowl champion. Turnarounds provide an unbelievably difficult training ground for young executives. It is sink or swim, it is kill or be killed. As discussed in our last book, Bill McDermott took over the struggling SAP North America division before righting the ship and accelerating SAP to growth. Frank Slootman began his managerial career in similar situations. After stints at Burroughs Corporation in corporate planning and Comshare in product management, Frank joined Compuware as head of non-mainframe Product Management. While there, Compuware acquired the dutch company, uniface, as we touched on in the Tape Sucks book. “I jumped at the opportunity return to Amsterdam to take on the entire operation, which seemed in disarray. Colleagues warned me not to go because the place could not be saved, and they worried I’d go down with the ship. Compuware had bought uniface toward the end of its viable product software. But by now, my career had been about taking on what seemed like long odds, jobs nobody else would touch with a 10 foot pole. It was the only avenue open to me anyway and it didn’t matter how hairy these deals were. As a young person, you easily overestimate your capabilities, this is when I started learning what happens when you step into the wrong elevators. We did manage to stabilize uniface. That became a formative career experience in my mid-30s. I’d never had multiple numerous large, mission-critical customers before and hundreds of employees in my charge. I also started to develop an eye for talent which became a cornerstone of my management focus going forward.” Next, Slootman jumped to Ecosystems, a Compuware subsidiary based in silicon valley. He stabilized the struggling company, but they kept losing talent because mid-western Compuware wasn’t able to retain silicon valley employees. He then joined Borland as SVP of product operations, which had also fallen on hard times. They resurrected the brand and the business. Even by 40 years old, he was taking on problem children, and he kept getting offered CEO jobs at companies that were elevators to nowhere. Slootman interviewed over and over for CEO roles but was passed on because “you’ve never run sales.” He later commented on being passed over: “I led from the front and sold shoulder to shoulder with sales. These rejections left me with an unfavorable opinion of many venture capitalists who couldn’t recognize talent if it smacked them in the face.” Turnarounds, especially those inside big companies offer management challenges that most people don’t get to experience until its too late. For Slootman and McDermott, these were the right opportunities for their personalities and approaches at the right time of their career.

Frank doesn’t believe in a Customer Success department. At Snowflake, there is no customer success department. In Slootman’s eyes: “They were happy to follow the trend set up by other companies like ours. But not me. I pulled the plug on these customer success departments in both companies, reassigning the staff back to the departments where their expertise fit best. Here’s why I was so opposed - if you have a customer success department that gives everyone else an incentive to stop worrying about how well our customers are thriving with our products and services. That sets up a disconnect that can create major problems down the road. People can become more focused on hitting the narrow goals of their silo rather than the broader and more important goal of customer satisfaction, which ultimately drives customer retention, word of mouth, profitability, and the long-term survival of the whole company. For instance, at ServiceNow, some of the customer success people grew quite dominant in the interaction with the customer and coordinated all the resources of the company for the customer’s benefit, including technical support, professional services, and even engineering. This had the effect that other departments sat back, became more passive, and felt less ownership of customer success. Customer success is the business of the entire company, not merely one department.” While this approach may work for Snowflake, it is not the norm in the SaaS world. In fact, there are entire companies like Gainsight, Totango, and ChurnZero, that help companies accelerate their Customer Success motion. Openview Venture Partners views customer success as critical for an effective product-led growth sales motion. Sales and Customer Success are important ways of generating product feedback from customers, but organizations need to make sure not to overwhelm product and engineering priorities. Often product teams don’t invest enough time in understanding the sales organization and the sales team views the product team as simply delivering on features to close deals. Leadership is necessary to help set priorities and collaboration across these departments.

5 steps to Amp it Up. Slootman outlines a five-step process for business leaders to accelerate growth and transform their organizations. The first step is to raise your standards and set ambitious goals for your company. This is followed by aligning your people and culture to support your vision, which requires careful attention to hiring, training, and communication. The third step is to sharpen your focus and prioritize the most critical areas of your business for growth. Once you have a clear focus, the fourth step is to pick up the pace and execute with speed and urgency. Finally, the fifth step is to transform your strategy by continually adapting to changes in the market and taking bold actions to stay ahead of the competition. By following these five steps, Slootman believes that business leaders can create a culture of high performance and achieve extraordinary results. Underpinning everything, is a culture of trust. Ultimately high performance cultures can be challenging and Slootman had times where former founders like Fred Luddy disagreed with his decisions. But as Slootman puts it: “In the long run, success trumps popularity. In my early days at several companies, founders openly regretted my hiring and openly complained to the board behind my back. But when companies succeed massively, as all of our companies have, founders will eventually get over it. Yes, its nice if they love you, but you can’t let yourself get rattled if they don’t. Your mission is to win, not to achieve popularity.”