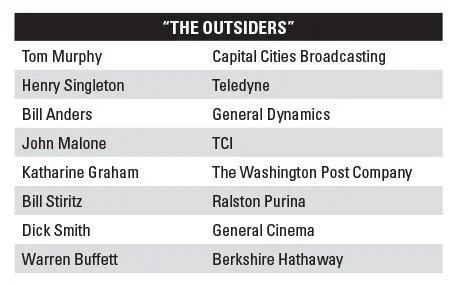

This month we read an absolute classic on capital allocation. Nothing says Outsider like multiple family businesses and white male HBS graduate CEOs! To be fair, many were “outsiders” to their industry. Either way, its a short and compelling read. Thorndike makes the point early in the book that this group of companies has outperformed the S&P over a prolonged period - but as an LP once said: “I’ve never seen a bad backtest.” I don’t view any of the practices in this book as rigid. These are not hammers to a nail, these are options for any executive considering the best use of cash.

Tech Themes

No straight lines. As is the case with many a business book, success is often portrayed as linear, despite being filled with the ups and downs that are natural in life. For example, when a young Tom Murphy took over a struggling radio station in Albany, he had to tightly manage the company through YEARS of operating losses, before he could turn on the offensive and start acquiring small competitors and buying back stock. Eventually, the cash generated from his businesses allowed him to acquire ABC for $3.5B in 1986, in a large extremely successful acquisition. Other Outsider CEOs also experienced challenges. Dick Smith’s General Cinema spin-off GCC went bankrupt in the late 1990s, as the cinema business became more competitive. Despite being an incredible CEO and capital allocator, Smith failed to save the initial company that generated the cash to build his business. When Bill Anders walked through the front door on his first day at General Dynamics, the company was bleeding cash, had a $600m mountain of debt, and a market cap of $1B despite $10B in annual revenues. Katharine Graham was thrust into the role of CEO at the Washington Post after her husband Philip Graham passed away. She was a mother of four, with little operating experience, stepping into the CEO role at a Fortune 500 company. Even the best CEOs experience the intensity of failing businesses, learning to push through the noise and emerge on the other side in tact can create the skill and resilience needed to thrive.

Improving Operations. Every CEO mentioned in the book was obsessive about improving operations and watching costs. Teledyne took a unique approach to driving operational discipline - they decentralized the organization. Driven by the need to diversify out of core businesses due to very restrictive M&A laws, the companies of the conglomerate era often acquired extremely diverse business interests and centralized operations to yield “synergies.” Teledyne took the opposite approach. Rather than rolling everything into one big corporate headquarters, they kept HQ lean, and pushed accountability and responsibility deep into their industrial subsidiaries. The result, managers that ran their organizations like owners, something Mark Leonard would be proud of. Bill Stiritz at Ralston Purina took a very aggressive approach to operational discipline. As Thorndike puts it: “Businesses that could not generate acceptable returns were sold (or closed). These divestitures included underperforming food brands (including the Van de Kamp’s frozen seafood division, a rare acquisition mistake) and the company’s legacy agricultural feed business.” Not only was Stiritz a hawk, carefully curating and watching his best business units, but he also was willing to let go of past mistakes to improve the core. This mental flexibility, and being able to not tie himself to an acquisition showed his extreme discipline in how he ran Ralston Purina. For a long time, the venture capital industry has provided substantial sums of cash to successful startups at ever climbing valuations, but these waves of cash can erode operational discipline that make CEOs great. We’ve seen a few companies (like Meta) embrace a new wave of efficiency

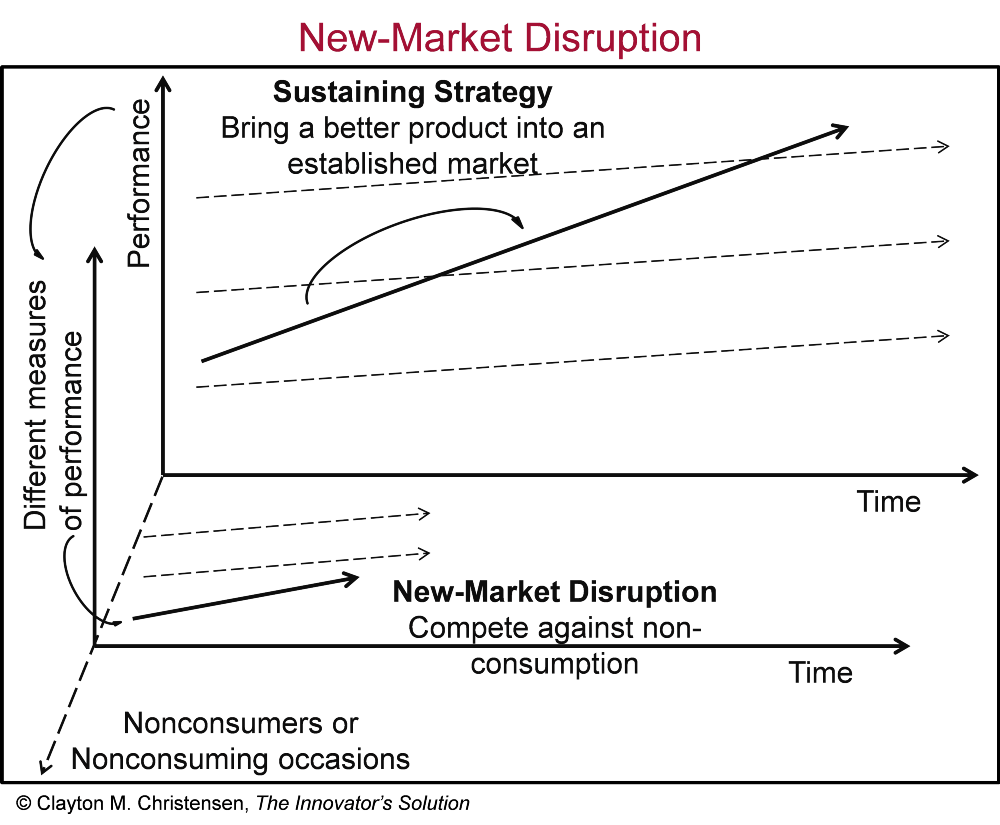

Winner Takes Most. Tom Murphy and Dan Burke were the perfect capital allocator (Tom) and disciplined operating executive (Dan) pair. They also knew Capital Cities business inside and out, to a point where they could truly understand the market, in a way only a competent insider with large swaths of information could. Thorndike writes: “Murphy and Burke realized that the key drivers of profitability in most of their businesses were revenue growth and advertising market share. For example, Murphy and Burke realized early on that the TV station that was number one in local news ended up with a disproportionate share of the market’s advertising revenue. As a result, Capital Cities stations always invested heavily in news talent and technology.” This idea around disproportionate share can also be called “Winner takes most,” and most software markets exhibit this dynamic. There are several reasons for this including Economies of Scale, Standardization, and Perceived Safety. Let’s take Atlassian’s Jira and Confluence through this lens. Because Atlassian is the largest provider of Product Management and Wiki software, it can spread its R&D costs across a very large number of users. The larger it gets, the lower per user cost it maintains. With the low distribution costs that software has, Atlassian can continually price its software extremely competitively to a point where its the best value (price to value received by customer) on the market. Software markets also tend to standardize on formats: think VHS vs. Betamax, HD DVD vs. Blue Ray, Apple vs. Microsoft/Intel. If the market is massive, there can be multiple winners (like Apple vs. Android or the three cloud providers). But once you become a standard in a medium to large sized market, it can be very difficult to flip that standard, because it takes re-jiggering the entire value chain. For example, a new product management software would mean software engineers, product/engineering managers, designers, and executives would need to all flip to a new standard. Its the reason Autodesk maintains a large market share, 40 years after the founding of AutoCAD. And this bring us to our last point, Perceived Safety. Brands are based on perceptions. Standards create the perception of safety - that they will exist in 10 years, that the executive choosing the standard won’t be fired for that choice, that the software will work at scale. Everyone hates on Jira, just like they hate on AutoCAD, or Salesforce, or Oracle. But these companies have all become standards, and individuals perceive standards as safe. Winner takes most markets are all about building that strong combination of price and value.

Business Themes

Buybacks, Acquisitions, Divestitures. One common trait from the outsider CEOs is not being shy when the market presents an incredible deal. Thorndike attempts to portray this as executives walking through simple math to come to straight forward conclusions. However, I believe this comes down to knowing exactly what you want. Tom Murphy, for example, kept a list of A+ assets he’d like to acquire (at a reasonable price) and waited until the time came, which is reminiscent of Chris Hohn’s approach too. Not that they couldn’t be flexible in approaching a new deal, but more that they had a very strong inkling of what and how financial returns could work and knew the competitive positioning of the assets they were purchasing deeply. Henry Singleton knew no business better than his own, and he flexed that muscle whenever the market gave him an opportunity to do so. As Thorndike says: “Henry Singleton is the Babe Ruth of repurchases… between 1972 and 1984, in eight separate tender offers, he bought back an astonishing 90% of Teledyne’s outstanding shares.” And Henry was not afraid of size nor leverage. “In May of 1980, with Teledyne’s P/E multiple near an all time low, Singleton initiated the comapny’s largest tender yet, which was oversubscribed by threefold. Singleton decided to buy all the tendered shares (over 20% of shares outstanding), and given the company’s strong free cash flow and a recent drop in interest rates, financed the entire repurchase with fixed rate debt.” We must be clear that buybacks are not always the right move and include many frictional costs that mean that not all shareholder dollars are being spent directly on share repurchases. Bill Stiritz of Ralston Purina was also not afraid to buy in size: “When the opportunity to buy Energizer came up, a small group of us met at 1:00pm and got the seller’s books. We performed a back of the envelope LBO model, met again at 4:00pm and decided to bid $1.4B”. Ralston would later spin Energizer Holdings out in 2000 for ~$2.1B, after selling off some smaller pieces of the business. About 20 months later, Ralston sold itself to Nestle for $10.3B. Stirtiz then began another consumer brands conglomerate with Post Holdings. Here, Stiritz was a buyer at one price, a seller at another, and a seller of his whole business at a huge take out price. At General Dynamics, Bill Anders refocused the company on areas where it could maintain a dominant market position. For example, General Dynamics owned the much lauded F-16 fighter plane division, but it was much smaller than industry counterpart Lockheed Martin. When Lockheed’s CEO offered him $1.5B for the division, an extremely high price (at the time), Anders sold it on the spot. Thorndike notes: “Anders made the rational business decision, the one that was consistent with growing per share value, even though it shrank his company to less than half its former size and robbed him of his favorite perk as CEO: the opportunity to fly the company’s cutting edge jets.” Looking back, the F16 went on to be a staple fighter plane in many militaries around the world, with individual contracts totaling well above $10B. I wonder if Anders still believes this was the best course of action for the company. It certainly saved it in the short term, but GD missed out on years of revenue from the F-16. Either way, Anders, along with other outsider CEOs weren’t afraid to shrink the company or grow the company via acquisitions, buybacks, and divestitures. Talk about the big acquisitions, big buybacks, big divestitures. Ralston-Energizer, Teledyne buying back a ton, Dick Smith buys and sales and spins.

Best Ideas Win. The outsider CEOs were totally willing to let others influence their decision making. Dick Smith created an Office of the Chairman, consisting of Chief Final Officer Woody Ives, Chief Operating Officer Bob Tarr, and corporate counsel Sam Frankenheim. As Thorndike writes: “Woody Ives, the company’s talented CFO, remembers one of his proudest moments at General Cinema (Ives later left to lead a successful turnaround at Eastern Resources), when a joint venture to enter the cable business with Comcast and CBS was shot down by the board after Smith let Ives voice a dissenting opinion: ‘He gave me permission to publicly disagree with him in front of the Board. Very few CEOs would have done that.” These CEOs thought logically, whether it was with the crowd or against. Henry Singleton put it well: “I know a lot of people have very strong and definite plans they’ve worked out all on all kinds of things, but we’re subject to a tremendous number of outside influences and the vast majority of them cannot be predicted. So my idea is to stay flexible.” Singleton and Buffett both shared a somewhat innate value orientation. When Leon Cooperman asked a retired Henry Singleton about the large number of share repurchases occurring at Fortune 500 companies, Henry responded: “If everyone’s doing them, there must be something wrong with them.” Many of the outsider CEOs also had unique ways of looking at the financials of their businesses. Singleton and CFO Jerry Jerome created a “Teledyne Return” which averaged cash flow and net income for each business unit and served as the basis for bonus compensation for all business unit managers. The Teledyne return idea is similar to Mark Leonard’s ROIC compensation scheme. Driven by his absolute disdain of taxes, John Malone at TCI introduced Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), as an alternative to reported earnings (Net income). Higher net income meant higher taxes and Malone liked to use leverage on his telecom buildouts to utilize debt’s natural interest tax shield. Dick Smith used cash earnings (net earnings + depreciation) when evaluating the success of his business units. Tom Murphy preferred ROIC: “The goal is not to have the longest train but to arrive at the station first using the least fuel.” The outsider CEOs thought independently and acted in accordance with anyone around the tables best ideas.

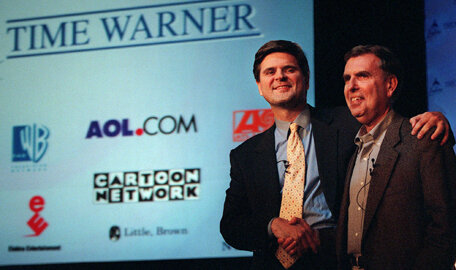

War time CEO. Not every decision these CEOs made went swimmingly. Teledyne faced an accounting probe, Dick Smith’s GCC went bankrupt, Bill Anders sold off a long-time winner to alleviate short term pressure, Bill Stiriz sold off Jack in the Box for $450m (now worth $4.5b) and the St. Louis Blues for $12m (now worth $1.3B), Warren Buffett acquired Dexter Shoe Company using 25,203 shares of stock (now worth $17B). When things got tough or extreme, they weren’t afraid to step back in to help in crucial moments. In the third quarter of 1996, TCI badly missed on its forecasts, losing subscribers for the first time and showing a decline in cash flow. “Malone, disappointed by these results reassumed the helm, and uncharacteristically, took direct management control of operations, quickly reducing employee head count by 2,500, halting all orders for capital equipment, and aggressively renegotiating programming contracts. He also fired the consultants who had been hired to help with the system upgrade, and returned responsibility for customer service to the local system managers.” Malone became the wartime CEO that Ben Horowitz discussed in The Hard Thing About Hard Things. Singleton retired from the chairman role at Teledyne in 1991 but “returned in 1996 to negotiate the merger of Teledyne’s manufacturing operations with Allegheny Industries and fend off a hostile takeover bid by raider Bennett LeBow.” Challenges inevitably strike every single business. As Bill Gurley likes to quip: “Every company eventually trades for 13x earnings.” His point being, that every company faces a moment where investors sour dramatically on the business’s future prospects. I’d even extend this to: “Every company eventually makes a compelling short.” Even some of the most vaunted businesses like Rollins, have stumbled into earnings management issues and become the focal point of short reports in recent years. If we think about businesses as complex, three dimensional functions, some portion of that function exists where market and business fundamentals eventually move against the company. Several outsider CEOs took that opportunity to jump back into the fire, and sort through the troubles, to land their businesses on the other side of the fray safely.

Dig Deeper