We cover Canada’s biggest and quietest software company and their brilliant leader Mark Leonard.

Tech Themes

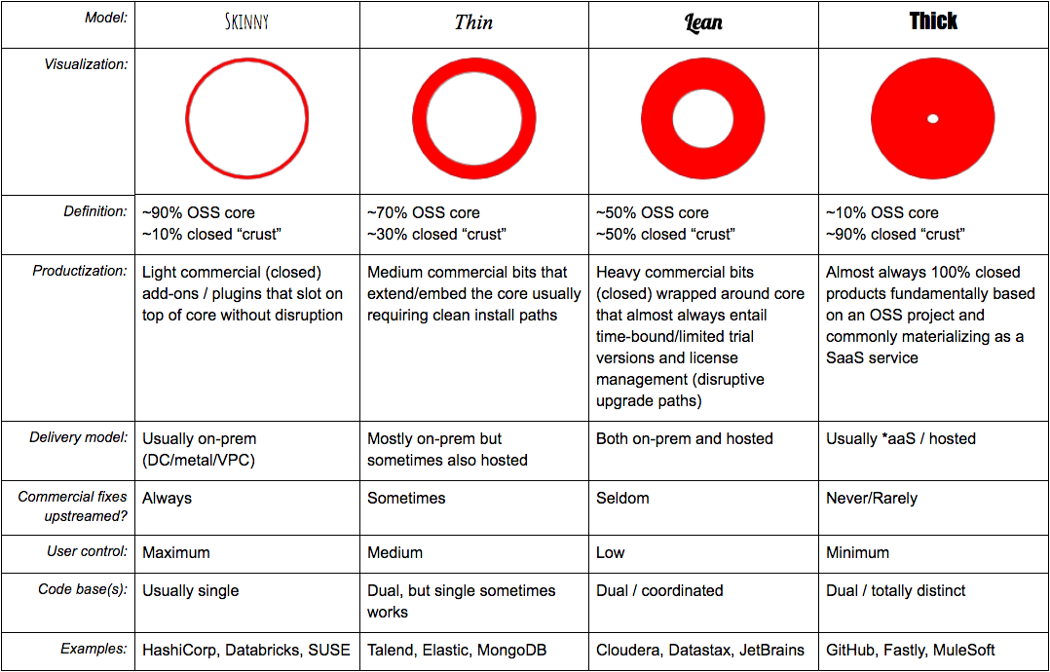

Critics and Critiques. For a long time, Constellation heard the same critiques: Roll-ups never work, the businesses you are buying are old, the markets you are buying in are small, the delivery method of license/maintenance is phasing out. All of these are valid concerns. Constellation is a roll-up of many software businesses. Roll-ups, aka acquiring several businesses as the primary method of growth, do have tendency to blow up. The most frequent version for a blowup is leverage. Companies finance acquisitions with debt and eventually they make a couple of poor acquisition decisions and the debt load is too big, and they go bankrupt. A recent example of this is Thrashio, an Amazon third party sellers roll-up. RetailTouchPoints lays out the simple strategy: “Back in 2021, firms like Thrasio were able to buy these Amazon-based businesses for around 4X to 6X EBITDA and then turn that into a 15X to 25X valuation on the combined business.” However, demand for many of these products waned in the post-pandemic era, and Thrasio had too much debt to handle with the lower amount of sales. Bankruptcy isn’t all bad - several companies have emerged from bankruptcy with restructured debt, in a better position than before. To avoid the issue of leverage, Constellation has never taken on meaningful (> 1-2x EBITDA) leverage. This may change in the coming years, but for now it remains accurate. Concerns around market size and delivery method (SaaS vs. License/Maintenance) are also valid. Constellation has software businesses in very niche markets, like boating maintenance software that are inherently limited in size. They will never have a $1B revenue boat maintenance software business, the market just isn’t that big. However, the lack of enthusiasm over a small niche market tends to offer better business characteristics - fewer competitors, more likely adoption of de-facto technology, highly specialized software that is core to a business. Constellation’s insight to combine thousands of these niche markets was brilliant. Lastly, delivery methods have changed. Most customers now prefer to buy cloud software, where they can access technology through a browser on any device and benefit from continuous upgrades. Furthermore, SaaS businesses are subscriptions compared to license maintenance businesses where you pay a signficant sum for the license up-front and then a correspondingly smaller sum for maintenance. SaaS subscriptions tend to cost more over the long-term and have less volatile revenue spikes, but can be less profitable because of the need to continuously improve products and provide the service 24/7. Interestingly, Constellation continued to avoid SaaS even after it was the dominant method of buying software. From the 2014 letter: “The SaaS’y businesses also have higher organic growth rates in recurring revenues than do our traditional businesses. Unfortunately, our SaaS’y businesses have higher average attrition, lower profitability and require a far higher percentage of new name client acquisition per annum to maintain their revenues. We continue to buy and invest in SaaS businesses and products. We'll either learn to run them better, or they will prove to be less financially attractive than our traditional businesses - I expect the former, but suspect that the latter will also prove to be true.” While 2014 was certainly earlier in the cloud transformation, its not surprising that an organization built around the financial characteristics of license maintenance software struggled to make this transition. They are finally embarking on this journey, led their by their customers, and its causing license revenue to decline. License revenue has declined each of the last six quarters. The critiques are valid but Constellations assiduousness allowed them to side-step and even benefit from these critics as they scaled.

Initiatives, Investing for Organic Growth, and Measurement. Although Leonard believes that organic growth is an important measure of success of a software company, he lays out in the Q1’07 letter the challenges of Constellation’s internal organic growth projects, dubbed Initiatives. “In 2003, we instituted a program to forecast and track many of the larger Initiatives that were embedded in our Core businesses (we define Initiatives as significant Research & Development and Sales and Marketing projects). Our Operating Groups responded by increasing the amount of investment that they categorized as Initiatives (e.g. a 3 fold increase in 2005, and almost another 50% increase during 2006). Initially, the associated Organic Revenue growth was strong. Several of the Initiatives became very successful. Others languished, and many of the worst Initiatives were terminated before they consumed significant amounts of capital.” The last sentence is the hardest one to stomach. Terminating initiatives before they had consumed lots of capital, is the smart thing to do. It is the rational thing to do. However, I believe this is at the heart of why Constellation has struggled with organic growth over time. Now I’ll be the first to admit that Constellation’s strategy has been incredible, and my criticism is in no way taking that away from them. Frankly, they won’t care what I say. But, as a very astute colleague pointed out to me, this position of measuring all internal R&D and S&M initiatives, is almost self-fulfilling. At the time Leonard wasn’t concerned with the potential for lack of internal investment and organic growth. He even remarked as so: “I’m not yet worried about our declining investment in Initiatives because I believe that it will be self-correcting. As we make fewer investments in new Initiatives, I’m confident that our remaining Initiatives will be the pick of the litter, and that they are likely to generate better returns. That will, in turn, encourage the Operating Groups to increase their investment in Initiatives. This cycle will take a while to play out, so I do not expect to see increased new Initiative investment for several quarters or even years.” By 2013, he had changed his tune: “Organic growth is, to my mind, the toughest management challenge in a software company, but potentially the most rewarding. The feedback cycle is very long, so experience and wisdom accrete at painfully slow rates. We tracked their progress every quarter, and pretty much every quarter the forecast IRR's eroded. Even the best Initiatives took more time and more investment than anticipated. As the data came in, two things happened at the business unit level: we started doing a better job of managing Initiatives, and our RDSM spending decreased. Some of the adaptations made were obvious: we worked hard to keep the early burn-rate of Initiatives down until we had a proof of concept and market acceptance, sometimes even getting clients to pay for the early development; we triaged Initiatives earlier if our key assumptions proved wrong; and we created dedicated Initiative Champion positions so an Initiative was less likely to drag on with a low but perpetual burn rate under a part-time leader who didn’t feel ultimately responsible. But the most surprising adaptation, was that the number of new Initiatives plummeted. By the time we stopped centrally collecting Initiative IRR data in Q4 2010, our RDSM spending as a percent of Net Revenue had hit an all-time low.” So how could the most calculating, strategic software company of maybe all time struggle to produce attractive organic growth prospects? I’d argue two things - 1) Incentives and 2) Rationality. First, on incentives, the Operating Group managers are compensated on ROIC and net revenue growth. If you are a BU manager and could invest in your business vs. buy another company that has declining organic growth but is priced appropriately (i.e. cheaply) requiring minimal capital outlay, you achieve both objectives by buying lower organic growers or even decliners. It is almost similar to buying ads to fill a hole in churned revenue. As long as you keep pressing the advertising button, you will keep gathering customers. But when you stop, it will be painful and growth will stall out. If I’m a BU manager buying meh software companies that achieve good ROIC and I’m growing revenues because of my acquisitions, it just means I need to keep finding more acquisitions to achieve my growth hurdles. Over time this is a challenge, but it may be multiple years before I have a bad acquisition growth year. Clearly, the incentives are not aligned for organic growth. Connected to the first point, the “buy growth for low cash outlays” strategy is perfectly rational based on the incentives. The key to its rationality is the known vs. the unknown. In buying a small, niche VMS business - way more is known about the range of outcomes. If you compare this to an organic growth initiative, it is clear why again, you choose the acquisition path. Organic growth investments are like venture capital. If sizeable, they can have an outsized impact on business potential. However, the returns are unknown. Simple probability illustrates that a 90% chance of a 20% ROIC and a 10% chance of a 10% ROIC, yields a 19% ROIC. I’d argue however, that with organic initiatives, particularly large, complex organic initiatives, there is an almost un-estimable return. If we use Amazon Web Services as perhaps the greatest organic growth initiative ever produced we can see why. Here is a reasonably capital-intensive business outside the core of Amazon’s online retailing applications. Sure, you can claim that they were already using AWS internally to run their operations, so the lift was not as strong. But it is still far afield from bookselling. AWS as an investment could never happen inside of Constellation (besides it being horizontal software). What manager is going to tank their ROIC via a capital-intensive initiative for several years to realize an astronomical gain down the line? What manager is going to send back to Constellation HQ, that they found a business that has the potential for $85B in revenue and $20B in operating profit 15 years out? You may say, “Vertical markets are small, they can’t produce large outcomes.” Constellation started after Veeva, a $30B public company, and Appfolio, a $7.5B company. The crux of the problem is that it is impossible to measure via a spreadsheet, the unknown and unknowable expected returns of the best organic growth initiatives. As Zeckhauser has discussed, the probabilities and associated gains/losses tend to be severely mispriced in these unknown and unknowable situations. Clayton Christensen identified this exact problem through his work on disruptive innovation. He urged companies to focus on ideas, failure, and learning, noting that strategic and financial planning must be discovery-based rather than execution based. Maybe there were great initiatives within Constellation that never got launched because incentives and rationality stopped them in their tracks. It’s not that you should burn the boats and put all your money into the hot new thing, it’s that product creation and organic growth are inherently risky ventures, and a certain amount of expected loss can be necessary to find the real money-makers.

Larger deals. Leonard stopped writing annual letters, but broke the streak in 2021, when he penned a short note, outlining that the company would be pursuing more larger deals at lower IRRs and looking to develop a new circle of competence outside of VMS. I believe his words were chosen carefully to reflect Warren Buffett’s discussion of Circle of Competence and Thomas Watson Sr.’s (founder of IBM) quote: “I’m no genius. I’m smart in spots - but I stay around those spots.” While I appreciate the idea behind it, I’m less inclined to stay within my circle of competence. I’m young, curious, and foolish, and I think it would be a waste to pigeon-hole myself so early. After all, Warren had to learn about insurance, banking, beverages, etc and he didn’t let his not-knowing preclude him from studying. In justifying larger deals, Leonard cited Constellation’s scale and ability to invest more effectively than current shareholders. He also laid out the company’s edge: “Most of our competitors maximise financial leverage and flip their acquisitions within 3-7 years. CSI appreciates the nuances of the VMS sector. We allow tremendous autonomy to our business unit managers. We are permanent and supportive stakeholders in the businesses that we control, even if their ultimate objective is to eventually be a publicly listed company. CSI’s unique philosophy will not appeal to all sellers and management teams, but we hope it will resonate with some.” Since then Constellation has acquired Allscript’s hospital unit business in March 2022 for $700m in cash, completed a spin-merger of Lumine Group into larger company, WideOrbit, to create a publicly traded telecom advertising software provider, and is rumored to be looking at purchasing a subsidiary of Black Knight, which may have to be divested for its own transaction with ICE. These larger deals no doubt come with more complexity, but one large benefit is they sit within larger operating groups, and are shielded during what may be difficult transition periods for the businesses. It allows the businesses to operate more long-term and focus on providing value to end customers. As for deals outside of VMS, Mark Leonard commented on it during the 2022 earnings call: “I took a hard look at a thermal oil situation. I was looking at close to $1B investment, and it was tax advantaged. So it was a clever structure. It was a time when the sector could not get financing. And unfortunately, the oil prices ran away on me. So I was trying to be opportunistic in a sector that was incredibly beat up. So that is an example….So what are the characteristics there? Complexity. Where its a troubled situation with — circumstances and there’s a lot of complexity. I think we can compete better than the average investor, particularly when people are willing to take capital forever.” The remark on complexity reminded me of Baupost, the firm founded by legendary investor Seth Klarman, who famously bought claims on Lehman Brothers Europe following the 2008 bankruptcy. When you have hyper rational individuals, complexity is their friend.

Business Themes

Decentralized Operating Groups. Its safe to say that Mark Leonard is a BIG believer in decentralized operating groups. Constellation believes in pushing as much decision making authority as possible to the leaders of the various business units. The company operates six operating groups: Volaris, Harris, Topicus (now public), Jonas, Perseus, and Vela. Leonard mentioned the organizational structure in the context of organic growth: “When most of our current Operating Group Managers ran single BU’s, they had strong organic growth businesses. As those managers gave up their original BU management position to oversee a larger Group of BU’s (i.e. became Portfolio Managers), the organic growth of their original BU’s decreased and the profitability of those BU’s increased.” As an example of this dynamic, we can look at Vencora, a Fintech subsidiary of Volaris. Vencora is managed by a portfolio manager, itself a collection of Business Units (BUs) with their own leadership. The Operating Group leaders and Portfolio Managers are incentivized based on growth and ROIC. Furthermore, Constellation mandates that at least 25% (for some executives its 75%) of incentive compensation must be used to purchase shares in the company, on the open market. These shares cannot be sold for three years. This incentive system accomplishes three goals: It keeps broad alignment toward the success of Constellation as a whole, it avoids stock dilution, and it creates a system where employees continuously own more and more of the business. Acquisitions above $20M in revenue must be approved by the head office, who is constantly receiving cash from different subsidiaries and allocating to the highest value opportunities. At varying times, the company has instituted “Keep your capital” initiatives, particularly for the Volaris and Vela operating groups. As Leonard points out in the 2015 letter: “One of the nice side effects of the “keep your capital” restriction, is that while it usually drives down ROIC, it generates higher growth, which is the other factor in the bonus formula. Acquisitions also tend to create an attractive increase in base salaries as the team ends up managing more people, capital, BUs, etc. Currently, a couple of our Operating Groups are generating very high returns without deploying much capital and we are getting to the point that we’ll ask them to keep their capital if they don’t close acceptable acquisitions or pursue acceptable Initiatives shortly.” Because bonuses are paid on ROIC, if an operating group manager sends back a ton of cash to corporate and doesn’t do a lot of new acquisitions, then its ROIC is very high and bonuses will be high. However, because Volaris and Vela are so large, it does not benefit the Head Office to continuously receive these large dividend payments and then pay high bonuses. Head Office will have a mountain of cash with out a lot of easy opportunities to deploy it. Thus the Keep your Capital initiative tamps down bonuses (by tamping down ROIC) and forces the leaders of these businesses to search out productive ways to deploy capital. As a result, more internal growth initiatives are likely to be funded, when acquisitions remain scarce, thereby increasing organic growth. It also pushes BUs and Portfolio Managers to seek out acquisitions to use up some of the capital. Overall, the organizational structure gives extreme authority to individuals and operates with large and strong incentives toward M&A and ROIC.

Selling Constellation. We all know about the epic “what would have happened” deals. A few that come to mind, Oracle buying TikTok US, Microsoft buying Yahoo for $55B, Yahoo acquiring Facebook, Facebook acquiring Snapchat, AT&T acquiring T-Mobile for $39B, JetBlue/Spirt, Ryanair/Aer Lingus. There are tons. Would you believe that Constellation was up for sale at one point? On April 4th 2011, the Constellation board announced that it was considering alternatives for the company. The company was $630m of revenue and $116m of Adj. EBITDA, growing revenue 44% year over year. Today, Constellation is $8.4B of revenue, with $1.16B of FCFA2S, growing revenue at 27% year over year. At the time, Leonard lamented: “I’m proud of the company that our employees and shareholders have built, and will be more than a little sad if it is sold.” To me, this is a critically important non-event to investigate. It goes to show that any company can prematurely cap its compounding. Today, Constellation is perhaps the most revered software company with the most beloved, mysterious genius leader. Imagine if Constellation had been bought by Oracle or another large software company? Where would Mark Leonard be today? Would we have the behemoth that exists today? After the process was concluded with no sale, Leonard discussed the importance of managing one’s own stock price. “I used to maintain that if we concentrated on fundamentals, then our stock price would take care of itself. The events of the last year have forced me to re-think that contention. I'm coming around to the belief that if our stock price strays too far (either high or low) from intrinsic value, then the business may suffer: Too low, and we may end up with the barbarians at the gate; too high, and we may lose previously loyal shareholders and shareholder-employees to more attractive opportunities.” Many technology CEOs could learn from Leonard, preserving an optimistic tone when the company is struggling or the market is punishing the company, and a pessimistic tone when the company is massively over-achieving, like COVID.

Metrics. Leonard loves thinking about and building custom metrics. As he stated in the Q4’2007 letter, “Our favorite single metric for measuring our corporate performance is the sum of ROIC and Organic Net Revenue Growth (“ROIC+OGr”).” However, he is constantly tinkering and thinking about the best and most interesting measures. He generally focuses on three types of metrics: growth, profitability, and returns. For growth, his preferred measure is organic growth. He also believes net maintenance growth is correlated with the value of the business. “We believe that Net Maintenance Revenue is one of the best indicators of the intrinsic value of a software company and that the operating profitability of a low growth software business should correlate tightly to Net Maintenance Revenues.” I believe this correlation is driven by maintenance revenue’s high profitability and association with high EBITA levels (Operating income + amortization from intangibles). For profitability metrics, Leonard for a long time preferred Adj. Net Income (ANI) or EBITA. “ One of the areas where generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”) do a poor job of reflecting economic reality, is with goodwill and intangibles accounting. As managers we are at least partly to blame in that we tend to ignore these “expenses”, focusing on EBITA or EBITDA or “Adjusted” Net Income (which excludes Amortisation). The implicit assumption when you ignore Amortisation, is that the economic life of the asset is perpetual. In many instances (for our business) that assumption is correct.” He floated the idea of using free cash flow per share, but it suffers from volatility depending on working capital payments and doesn’t adjust for minority interest payments. Adj. Net Income does both of these things but doesn’t capture the actual cash into the business. In Q3’2019, Leonard adopted a new metric called Free Cash Flow Available to Shareholders (FCFA2S): “We calculate FCFA2S by taking net cash flow from operating activities per IFRS, subtracting the amounts that we spend on fixed assets and on servicing the capital we have sourced from other stakeholders (e.g. debt providers, lease providers, minority shareholders), and then adding interest and dividends earned on investments. The remaining FCFA2S is the uncommitted cashflow available to CSI's shareholders if we made no further acquisitions, nor repaid our other capital-providing stakeholders.” FCFA2S achieves a few happy mediums: 1) Similar to ANI, it is net of the cost of servicing capital (interest, dividends, lease payments) 2) It captures changes in working capital, while ANI does not 3) It reflects cash taxes as opposed to current taxes deducted from pre-tax income (this gets at a much more confusing discussion on deferred tax assets and the difference between book taxes and cash taxes) 4) When comparing FCFA2S to CFO, it tends to be closer than comparing ANI to reported net income. For return metrics, Leonard prefers ROIC (ANI/Average Invested Capital). In the 2015 letter, he laid out the challenge of this metric. First, ROIC can be infinity if a company grows large while reducing its working capital (common in software), effectively lowering the purchase price to zero. Infinity ROIC is a problem because bonuses are paid on ROIC. He contrasts ROIC with IRR but notes its drawbacks, that IRR does not indicate the hold period nor size of the investments. As is said at investing firms, “You can’t eat IRR.” In the 2017 letter, he discussed Incremental return on incremental invested capital ((ANI1 - ANI0)/(IC1-ICo)), but noted its volatility and challenge with handling share issuances / repurchases. Share issuances would increase IC, without an increase in ANI. When discussing high performance conglomerates (HPCs), he discusses EBITA Return (EBITA/Average Total Capital). He notes that: “ROIC is the return on the shareholders’ investment and EBITA Return is the return on all capital. In the former, financial leverage plays a role. In the latter only the operating efficiency with which all net assets are used is reflected, irrespective of whether those assets are financed with debt or shareholders’ investment.” This is similar to P/E vs. EV/EBITDA multiples, where P/E multiples should be used to value market capitalization (i.e. Price) while EV/EBITDA should be used to value the entirety of the business as it relates to debt and equityholders. Mark Leonard is a man of metrics, we will keep watching to see what he comes up with next! In this spirit, I will try to offer a metric for fast-growing software companies, where ROIC is effectively meaningless because negative working capital dynamics in software produce negative invested capital. Furthermore, faster growing companies generally spend ahead of growth and lose money so ANI, FCF, EBITA are all lower than they should be. If you believe the value of these businesses is closely related to revenue, you could use S&M efficiency, or net new ARR / S&M spend. While a helpful measure, many companies don’t disclose ARR. Furthermore, this doesn’t incorporate perhaps the most expensive investing cost, developing products. It also does not incorporate gross margins, which can vary between 50-90% for software companies. One metric you could use is incremental gross margin / (incremental S&M, R&D costs). Here the challenge would be the years it takes to develop products and GTM distribution. To get around this, you could use a cumulative number for R&D/S&M costs. You could also use future gross margin dollars and offset them, similar to the magic number. So our metric is 3 year + incremental gross margin / cumulative S&M and R&D costs. Not a great metric but it can’t hurt to try!

Dig Deeper