This month we learn about the crazy culture at Uber and how it perpetrated repeated discrimination against groups of people, until someone did something about it. Then Susan Fowler - a software engineer at Uber, put pen to paper on a seminal blog post that upended Uber and the world.

Tech Themes

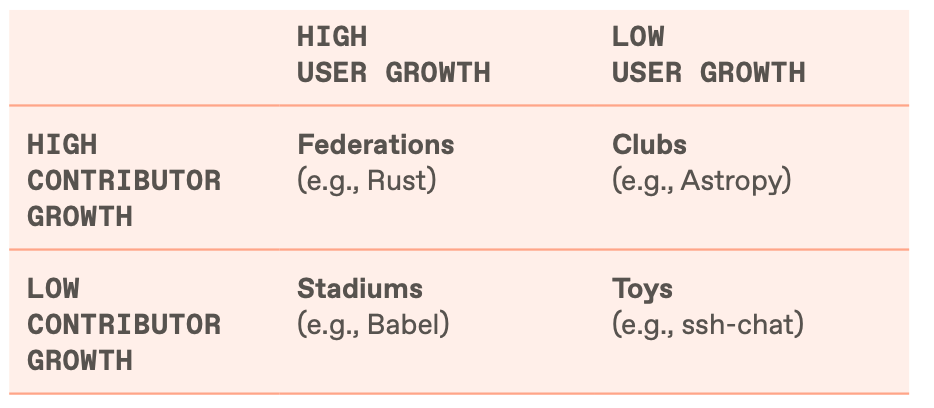

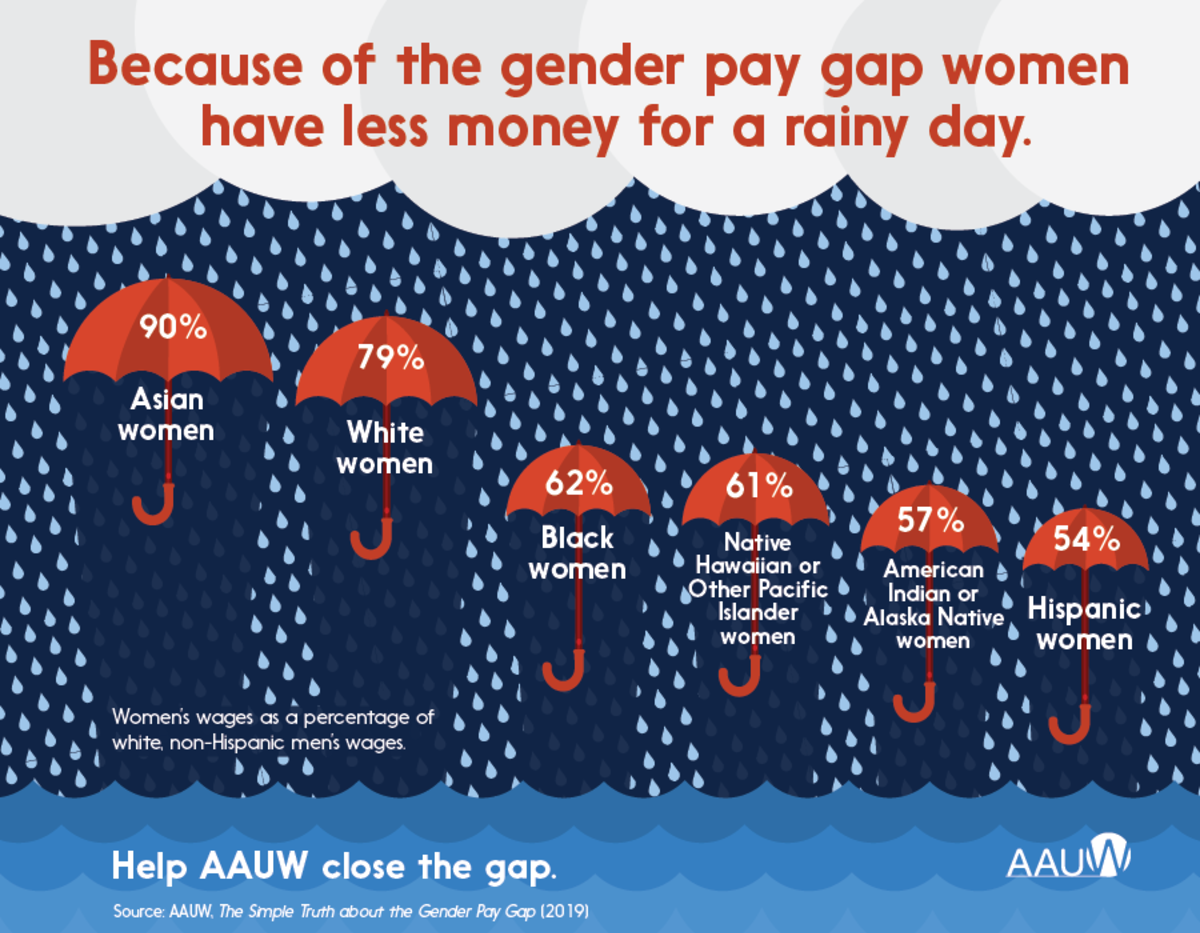

Software Engineering Diversity. Diversity has been a challenge for technology companies, despite overwhelming rhetoric about its importance. A 2022 report by Celential.ai highlighted that only 21% of software engineers are women. More concerning, is that this percentage has been falling in recent years, with zippia estimating that the percentage of female software engineers was closer to ~31% in 2011. Susan Fowler experienced this sad statistic multiple times - when she joined Plaid, a fintech startup with 13 employees, there were only two women. After switching to the networking startup, Pubnub, Fowler found herself the only woman on the engineering team, which was made worse by her boss who was “openly, unabashedly sexist.” So Fowler was very excited when her interviewer at Uber noted: “Twenty-five percent of our engineers are women.” But that joy was short-lived. Just one year after receiving her team assignment (Site reliability engineering), her team had gone from 25% women to just 6% due to repeated harassment by team managers. Sadly, sexual harassment seems like the norm in the tech industry with 78% of female founders saying they’ve been sexually harassed or know someone else who has. The tech industry has a lot to improve to make companies more diverse with less harassment.

Abuse, Burnout, and Fatigue. Software engineering can be a grind. Day in, and day out, you are typing at your computer, sometimes rarely interacting with other people. Fowler quickly figured out that Uber’s managers had a common approach to get people motivated, negative personal attacks and abuse. As Fowler noted relatively early on in her Uber journey: “I dreaded going into work, knowing that I’d be yelled at in meetings, that I’d be told I wasn’t ‘doing my job,’ that I wasn’t ‘working hard enough,’ even though I was doing everything that my managers asked of me. I wasn’t the only one who felt this way. When I told my friends in the other site reliability engineering teams what was going on, they said they had the same problems with their managers and teams, too. Almost every single one of them had started seeing a therapist for anxiety and depression related to the culture of work at uber; the engineers who had been at uber the longest all seemed to have suicidal thoughts.” Fowler was determined to escape this constant anxiety, so she applied to switch teams, only to have the transfer blocked by her manager. Her manager went so far as to imply that women couldn’t be good site reliability engineers, claiming “ Some people have things about them that are performance problems. These aren’t things about their work or the kind of work they do, but who they are.” Insane! Abuse, depression, anxiety, and burnout are sadly norms in the tech world, with 60% of tech workers reporting burnout in a team Blind survey. Tech cultures can feed on themselves with increasing hours leading to small productivity gains that lead to promotions and an ever-intensifying culture. Some gave developers have worked 24 hours straight testing games. The software engineering world needs better managers that understand how to help engineers avoid burnout.

Site Reliability Engineering. Fowler worked as a Site Reliability Engineer at Uber, which is a relatively new engineering role that was popularized by Google. According to Red Hat, “SRE teams use software as a tool to manage systems, solve problems, and automate operations tasks.” Site Reliability Engineering generally manages production infrastructure and ensure that companies can meet their Service Level Agreements for service uptime. When Fowler joined Uber, she noticed that the company lacked standardization across its SRE practices. Fowler noted: “Over a thousand independent microservices, spread out across countless engineering teams, all had to work together for the Uber app to function correctly; these microservices didn’t always work together the way they needed to, and the lack of standardization was large to blame. Whenever these systems failed because they didn’t meet the basic standards of building reliable software, it meant that riders were abandoned, drivers weren’t paid, and destinations were lost mid-trip.” Fowler tackled this problem by compiling a list of architecture standards that worked for each team, and then devised a system to certify that microservices were “production-ready.” Her work helped improve the standards for software at Uber and increased their micro-service uptime.

Business Themes

Stoicism and Doing What's Right. Susan Fowler was an outsider to Silicon Valley. She grew up in poverty in a rural suburb of Phoenix. Her parents were faithful believers in Christianity, and her Dad worked as a pastor while her mother stayed at home and homeschooled her children. However, when Fowler got to high school, her Mom re-entered the workforce as a teacher, and her Dad decided to pursue a degree in education. Despite trying desperately to enter the public school system, Fowler was rebuffed and told that she wasn't competent enough to enroll in an Arizona high school. As a result, she got a job working as a nanny and studied textbooks at night with the hope of schooling herself. During this intensely lonely period of her life, she rediscovered some of her favorite books, including the Greek philosophers known as the stoics. Fowler recalls the pivotal moment of her life: "As I sat there among the books that I had been reading for the last few years, thinking about the stories that they told of great people and the great things they had done, it suddenly occurred to me: these were stories about people who had done things in their lives, not had things done to them, who had made things happen in their lives, not had things happen to them." This revelation prompted a seething desire to get a formal education and gain personal autonomy. She accomplished this by attending Arizona State, then the University of Pennsylvania, and ultimately graduating with a degree in physics. The stoic mindset was pivotal in her decision to ultimately publish the blog post that made her famous. The Stoics teach that you must do was is morally right. Fowler recalls: "I didn't know what to do. I felt, deep in my heart that writing my story and sharing it with the world was the right thing to do but the possible consequences were so awful that I couldn't believe it was something I was actually morally obligated to do...And then it hit me: I had no way of possibly knowing what the consequences of my actions would be. I had no idea what would actually happen if I wrote the blog." Fowler's philosophical growth laid the foundation for her to speak out when she saw truly abhorrent behavior, and the world is undeniably better for it.

Early Culture Importance. As ride-hailing platforms exploded world-wide, Uber was a business in open defiance of the law. "Travis Kalanick and his team were operating in cities across the world without permission, unashamedly breaking and disregarding laws and regulations – all in the name of 'hustle' and 'disruption.'" The HBO series about Uber called Superpumped, an Uber cultural value, depicts this intense hustle-or-die culture. Beyond the abuse, the sexual harassment, and the HR violations, Uber filled its management ranks with corporate ladder climbers clamoring for closer positions to "TK." Fowler recalled: "Nothing was off-limits in these petty power games: projects were sabotaged, rumors were spread, employees were used as pawns." Interestingly enough, Uber had all the makings of what would be considered good diversity and inclusion practices – unconscious bias training, anti-harassment, and anti-discrimination training, employee surveys, support groups, women on the board, and women in management positions. But the company was rotten from the inside out because of its operations. "The issue wasn't that Uber needed to be more diverse and inclusive; the issue was that Uber had a culture that ignored and violated civil and employment laws." Uber had 14 cultural values, which is too many for any company. Culture is established early in companies and can be the complete unwinding of a company if not very carefully managed as the company grows.

Human Resources. Nothing exemplifies Uber's broken culture more than Fowler's disturbing first day on her SRE team. As she sat down to work finishing up onboarding tasks, her new manager Jake started to slack her incessantly about his open relationship and approach to sexual relationships. Because of Susan's past dealing with the completely unjust due process at Penn, she immediately screenshotted the messages and promptly reported Jake to HR. However, after a brief meeting in a different building, she was told that this was Jake's first offense and that the company wouldn't be taking any action against him. Later, Fowler would uncover that numerous people had complained specifically about Jake and Uber had lobbied the same excuse. This inexplicable communication was just the beginning of HR nightmares at Uber – some of which violated employment law. So what were the issues with Uber's HR department? First, Uber's HR department was woefully small, with one source suggesting it was close to 10 people to manage 11,000 employees. In addition, the Head of HR reported to Ryan Graves, a co-founder and its then Head of operations, rather than CEO Travis Kalanick. This misalignment in reporting structure meant that Renee Atwood, then Head of HR, had to report challenging HR situations to Graves, whom some claimed wasn't equipped to handle the growing complexity of these situations appropriately. To handle the mounting controversies surrounding Uber after Fowler's blog post, the board hired Eric Holder, a former US Attorney General to investigate Fowler's claims. The final report is mostly internal, but the recommendations of Holder's firm Covington are public. When all was said and done, Uber fired Travis Kalanick, and replaced him with Dara Khosrowshahi, a former Expedia CEO and Allen and Co. Managing Director.