This month we take another look at disruptive innovation in the counter piece to Clayton Christensen’s Innovator’s Dilemma, our July 2020 book. The book crystallizes the types of disruptive innovation and provides frameworks for how incumbents can introduce or combat these innovations. The book was a pleasure to read and will serve as a great reference for the future.

Tech Themes

Integration and Outsourcing. Today, technology companies rely on a variety of software tools and open source components to build their products. When you stitch all of these components together, you get the full product architecture. A great example is seen here with Gitlab, an SMB DevOps provider. They have Postgres for a relational database, Redis for caching, NGINX for request routing, Sentry for monitoring and error tracking and so on. Each of these subsystems interacts with each other to form the powerful Gitlab project. These interaction points are called interfaces. The key product development question for companies is: “Which things do I build internally and which do I outsource?” A simple answer offered by many MBA students is “Outsource everything that is not part of your core competence.” As Clayton Christensen points out, “The problem with core-competence/not-your-core-competence categorization is that what might seem to be a non-core activity today might become an absolutely critical competence to have mastered in a proprietary way in the future, and vice versa.” A great example that we’ve discussed before is IBM’s decision to go with Microsoft DOS for its Operating System and Intel for its Microprocessor. At the time, IBM thought it was making a strategic decision to outsource things that were not within its core competence but they inadvertently gave almost all of the industry profits from personal computing to Intel and Microsoft. Other competitors copied their modular approach and the whole industry slugged it out on price. The question of whether to outsource really depends on what might be important in the future. But that is difficult to predict, so the question of integration vs. outsourcing really comes down to the state of the product and market itself: is this product “not good enough” yet? If the answer is yes, then a proprietary, integrated architecture is likely needed just to make the actual product work for customers. Over time, as competitors enter the market and the fully integrated platform becomes more commoditized, the individual subsystems become increasingly important competitive drivers. So the decision to outsource or build internally must be made on the status of product and the market its attacking.

Commoditization within Stacks. The above point leads to the unbelievable idea of how companies fall into the commoditization trap. This happens from overshooting, where companies create products that are too good (which I find counter-intuitive, who thought that doing your job really well would cause customers to leave!). Christensen describes this through the lens of a salesperson “‘Why can’t they see that our product is better than the competition? They’re treating it like a commodity!’ This is evidence of overshooting…there is a performance surplus. Customers are happy to accept improved products, but unwilling to pay a premium price to get them.” At this time, the things demanded by customers flip - they are willing to pay premium prices for innovations along a new trajectory of performance, most likely speed, convenience, and customization. “The pressure of competing along this new trajectory of improvement forces a gradual evolution in product architectures, away from the interdependent, proprietary architectures that had the advantage in the not-good-enough era toward modular designs in the era of performance surplus. In a modular world, you can prosper by outsourcing or by supplying just one element.” This process of integration, to modularization and back, is super fascinating. As an example of modularization, let’s take the streaming company Confluent, the makers of the open-source software project Apache Kafka. Confluent offers a real-time communications service that allows companies to stream data (as events) rather than batching large data transfers. Their product is often a sub-system underpinning real-time applications, like providing data to traders at Citigroup. Clearly, the basis of competition in trading has pivoted over the years as more and more banking companies offer the service. Companies are prioritizing a new axis, speed, to differentiate amongst competing services, and when speed is the basis of competition, you use Confluent and Kafka to beat out the competition. Now let’s fast forward five years and assume all banks use Kafka and Confluent for their traders, the modular sub-system is thus commoditized. What happens? I’d posit that the axis would shift again, maybe towards convenience, or customization where traders want specific info displayed maybe on a mobile phone or tablet. The fundamental idea is that “Disruption and commoditization can be seen as two sides of the same coin. That’s because the process of commoditization initiates a reciprocal process of de-commoditization [somewhere else in the stack].”

The Disruptive Becomes the Disruptor. Disruption is a relative term. As we’ve discussed previously, disruption is often mischaracterized as startups enter markets and challenge incumbents. Disruption is really a focused and contextual concept whereby products that are “not good enough” by market standards enter a market with a simpler, more convenient, or less expensive product. These products and markets are often dismissed by incumbents or even ceded by market leaders as those leaders continue to move up-market to chase even bigger customers. Its fascinating to watch the disruptive become the disrupted. A great example would be department stores - initially, Macy’s offered a massive selection that couldn’t be found in any single store and customers loved it. They did this by turning inventory three times per year with 40% gross margins for a 120% return on capital invested in inventory. In the 1960s, Walmart and Kmart attacked the full-service department stores by offering a similar selection at much cheaper prices. They did this by setting up a value system whereby they could make 23% gross margins but turn inventories 5 times per year, enabling them to earn the industry golden 120% return on capital invested in inventory. Full-service department stores decided not to compete against these lower gross margin products and shifted more space to beauty and cosmetics that offered even higher gross margins (55%) than the 40% they were used to. This meant they could increase their return on capital invested in inventory and their profits while avoiding a competitive threat. This process continued with discount stores eventually pushing Macy’s out of most categories until Macy’s had nowhere to go. All of a sudden the initially disruptive department stores had become disrupted. We see this in technology markets as well. I’m not 100% this qualifies but think about Salesforce and Oracle. Marc Benioff had spent a number of years at Oracle and left to start Salesforce, which pioneered selling subscription, cloud software, on a per-seat revenue model. This meant a much cheaper option compared to traditional Oracle/Siebel CRM software. Salesforce was initially adopted by smaller customers that didn’t need the feature-rich platform offered by Oracle. Oracle dismissed Salesforce as competition even as Oracle CEO Larry Ellison seeded Salesforce and sat on Salesforce’s board. Today, Salesforce is a $200B company and briefly passed Oracle in market cap a few months ago. But now, Salesforce has raised its prices and mostly targets large enterprise buyers to hit its ambitious growth initiatives. Down-market competitors like Hubspot have come into the market with cheaper solutions and more fully integrated marketing tools to help smaller businesses that aren’t ready for a fully-featured Salesforce platform. Disruption is always contextual and it never stops.

Business Themes

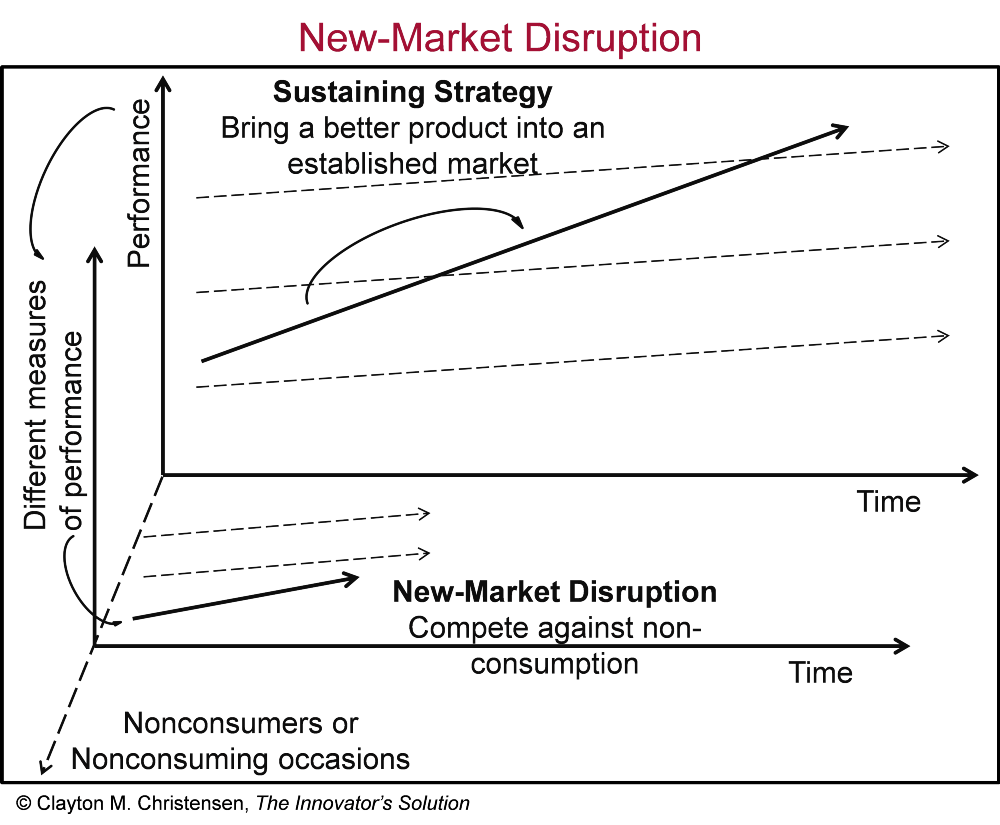

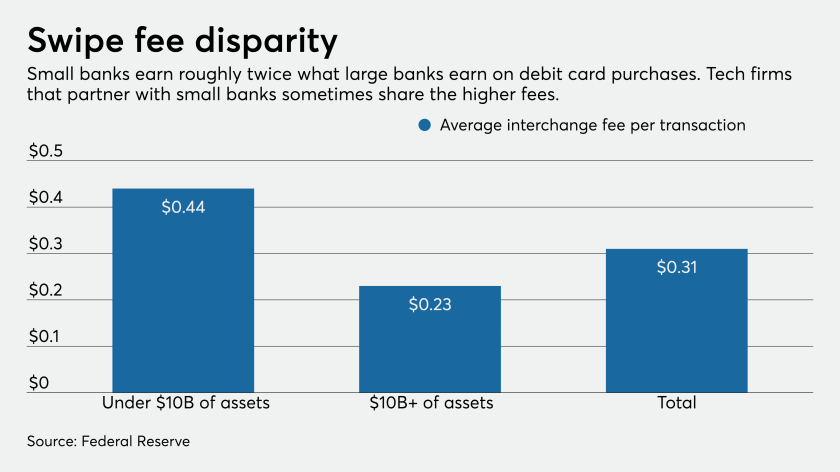

Low-end-Market vs. New-Market Disruption. There are two types of established methods for disruption: Low-end-market (Down-market) and New-market. Low-end-market disruption seeks to establish performance that is “not good enough” along traditional lines, and targets overserved customers in the low-end of the mainstream market. It typically utilizes a new operating or financial approach with structurally different margins than up-market competitors. Amazon.com is a quintessential low-end market disruptor compared to traditional bookstores, offering prices so low they angered book publishers while offering unmatched convenience to customers allowing them to purchase books online. In contrast, Robinhood is a great example of a new-market disruption. Traditional discount brokerages like Charles Schwab and Fidelity had been around for a while (themselves disruptors of full-service models like Morgan Stanley Wealth Management). But Robinhood targeted a group of people that weren’t consuming in the market, namely teens and millennials, and they did it in an easy-to-use app with a much better user interface compared to Schwab and Fidelity. Robinhood also pioneered new pricing with zero-fee trading and made revenue via a new financial approach, payment for order flow (PFOF). Robinhood makes money by being a data provider to market makers - basically, large hedge funds, like Citadel, pay Robinhood for data on their transactions to help optimize customers buying and selling prices. When approaching big markets its important to ask: Is this targeted at a non-consumer today or am I competing at a structurally lower margin with a new financial model and a “not quite good enough” product? This determines whether you are providing a low-end market disruption or a new-market disruption.

Jobs To Be Done. The jobs to be done framework was one of the most important frameworks that Clayton Christensen ever introduced. Marketers typically use advertising platforms like Facebook and Google to target specific demographics with their ads. These segments are narrowly defined: “Males over 55, living in New York City, with household income above $100,000.” The issue with this categorization method is that while these are attributes that may be correlated with a product purchase, customers do not look up exactly how marketers expect them to behave and purchase the products expected by their attributes. There may be a correlation but simply targeting certain demographics does not yield a great result. The marketers need to understand why the customer is adopting the product. This is where the Jobs to Be Done framework comes in. As Christensen describes it, “Customers - people and companies - have ‘jobs’ that arise regularly and need to get done. When customers become aware of a job that they need to get done in their lives, they look around for a product or service that they can ‘hire’ to get the job done. Their thought processes originate with an awareness of needing to get something done, and then they set out to hire something or someone to do the job as effectively, conveniently, and inexpensively as possible.” Christensen zeroes in on the contextual adoption of products; it is the circumstance and not the demographics that matter most. Christensen describes ways for people to view competition and feature development through the Jobs to Be Done lens using Blackberry as an example (later disrupted by the iPhone). While the immature smartphone market was seeing feature competition from Microsoft, Motorola, and Nokia, Blackberry and its parent company RIM came out with a simple to use device that allowed for short productivity bursts when the time was available. This meant they leaned into features that competed not with other smartphone providers (like better cellular reception), but rather things that allowed for these easy “productive” sessions like email, wall street journal updates, and simple games. The Blackberry was later disrupted by the iPhone which offered more interesting applications in an easier to use package. Interestingly, the first iPhone shipped without an app store (but as a proprietary, interdependent product) and was viewed as not good enough for work purposes, allowing the Blackberry to co-exist. Management even dismissed the iPhone as a competitor initially. It wasn’t long until the iPhone caught up and eventually surpassed the Blackberry as the world’s leading mobile phone.

Brand Strategies. Companies may choose to address customers in a number of different circumstances and address a number of Jobs to Be Done. It’s important that the Company establishes specific ways of communicating the circumstance to the customer. Branding is powerful, something that Warren Buffett, Terry Smith, and Clayton Christensen have all recognized as durable growth providers. As Christensen puts it: “Brands are, at the beginning, hollow words into which marketers stuff meaning. if a brand’s meaning is positioned on a job to be done, then when the job arises in a customer’s life, he or she will remember the brand and hire the product. Customers pay significant premiums for brands that do a job well.” So what can a large corporate company do when faced with a disruptive challenger to its branding turf? It’s simple - add a word to their leading brand, targeted at the circumstance in which a customer might find themself. Think about Marriott, one of the leading hotel chains. They offer a number of hotel brands: Courtyard by Marriott for business travel, Residence Inn by Marriott for a home away from home, the Ritz Carlton for high-end luxurious stays, Marriott Vacation Club for resort destination hotels. Each brand is targeted at a different Job to Be Done and customers intuitively understand what the brands stand for based on experience or advertising. A great technology example is Amazon Web Services (AWS), the cloud computing division of Amazon.com. Amazon invented the cloud, and rather than launch with the Amazon.com brand, which might have confused their normal e-commerce customers, they created a completely new brand targeted at a different set of buyers and problems, that maintained the quality and recognition that Amazon had become known for. Another great retail example is the SNKRs app released by Nike. Nike understands that some customers are sneakerheads, and want to know the latest about all Nike shoe drops, so Nike created a distinct, branded app called SNKRS, that gives news and updates on the latest, trendiest sneakers. These buyers might not be interested in logging into the Nike app and may become angry after sifting through all of the different types of apparel offered by Nike, just to find new shoes. The SNKRS app offers a new set of consumers and an easy way to find what they are looking for (convenience), which benefits Nike’s core business. Branding is powerful, and understanding the Job to Be Done helps focus the right brand for the right job.