We learn about the fun history of many monopolies and anti-trust! While I can’t recommend this book because its long and poorly written, it does reasonably critique aspects of antitrust and monopoly formation. Its repetitive and so aggressively one-sided that it loses credibility. The fact that the author used to advise and now runs a hedge fund that owns monopoly businesses tells you all you need to know.

Tech Themes

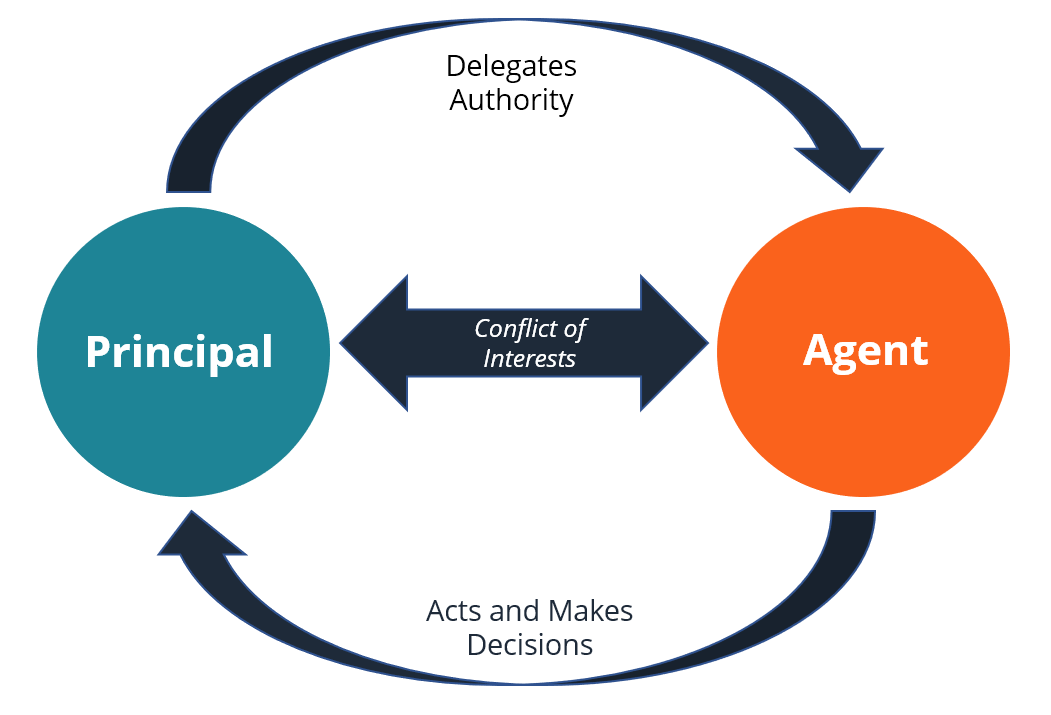

Consumer Welfare. Tepper’s fundamental argument is that since the 1980s, driven by Regan’s deregulation push, the government has allowed corporate mergers and abuses of market power, leading to more market concentration, higher prices, greater inequality, worse worker conditions, and stymied innovation. Influenced by the Chicago School’s free market ideas and Robert Bork’s popular 1978 book Antitrust Paradox, the standard for antitrust enforcement morphed from breaking up market-abusing companies to “consumer welfare.” With this shift, antitrust enforcement became: “Does this harm the consumer?” A lot of things do not harm consumers. Broadcast Music, Inc. v. CBS, Inc. (1979) is widely regarded as one of the first antitrust cases that shifted the Rule of reason towards consumer welfare. CBS had sued Broadcast Music, alleging that blanket licenses constituted price fixing. Broadcast Music represented copyright holders and would grant licenses to media companies to use artist’s music on air. These deals were negotiated on behalf of many artists, and did not allow CBS to negotiate for selected works. The court sided with BMI because the blanket license process was simpler, lowered transaction costs by reducing the number of negotiations, and allowed broadcasters greater access to works. They even admitted that the blanket license may be a form of price setting, but concluded that it didn’t necessarily harm consumers and was more efficient, so they allowed it. The consumer welfare ideology has recently come under fire around the big tech companies - Apple, Microsoft, Google, Meta, and Amazon. Lina Khan, Commissioner of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) wrote a powerful and aptly titled article, Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox, highlighting why in her view consumer welfare was not a strong enough stance on antitrust. “This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competition to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy.” The note argues that Amazon’s willingness to offer unsustainably low prices and their role as a marketplace platform and a seller on that marketplace allow it crush competition. Google is currently being sued by the Department of Justice over illegal monopolization of adtech and its dominance in the search engine market. The government is attempting to shift antitrust back to a more aggressive approach regarding monopolistic behavior. From a consumer welfare perspective, there is no doubt that all of these companies have created situations that benefit consumers (“free” services, low prices) and hurt competition. The question is: “Is it illegal?”

The ACTs - Sherman and Clayton. The Sherman Antitrust Act, passed in 1890, was the first major federal law aimed at curbing monopolies and promoting competition. The late 19th century, often referred to as the Gilded Age, saw the rise of powerful industrialists like J.P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, whose massive corporations threatened to dominate key sectors of the economy. Public outcry over the potential for these monopolies to stifle competition and exploit consumers led to the passage of the Sherman Act. Senator John Sherman, intended the law to protect the public from the negative consequences of concentrated economic power. The Sherman Act broadly prohibited anticompetitive agreements and monopolization, empowering the government to break up monopolies and prevent practices that restrained trade. However, the Sherman Act's broad language left it open to interpretation, and its early enforcement was inconsistent. President Theodore Roosevelt, a proponent of trust-busting, used the Sherman Act to challenge powerful monopolies, such as the Northern Securities Company, a railroad conglomerate controlled by J.P. Morgan. The Supreme Court's decision in the Standard Oil case in 1911 further shaped the interpretation of the Sherman Act, establishing the "rule of reason" as the standard for evaluating antitrust violations. This meant that not all restraints of trade were illegal, only those that were deemed "unreasonable" in their impact on competition. The Clayton Antitrust Act, passed in 1914, was designed to strengthen and clarify the Sherman Act. It specifically targeted practices not explicitly covered by the Sherman Act, such as mergers and acquisitions that could lessen competition, price discrimination, and interlocking directorates. The Clayton Act also sought to protect labor unions, which had been subject to antitrust prosecution under the Sherman Act. The passage of these acts led to a wave of significant antitrust cases. Prominent examples include: United States v. American Tobacco Co. (1911): This case resulted in the breakup of the American Tobacco Company, a dominant force in the tobacco industry, demonstrating the government's commitment to using antitrust laws to dismantle powerful monopolies. United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc. (1948): This case challenged the vertical integration of the film industry, where major studios controlled production, distribution, and exhibition. The court's decision led to significant changes in the industry's structure. United States v. AT&T Co. (1982): This landmark case resulted in the breakup of AT&T, a telecommunications giant, into smaller, regional companies. This case marked a major victory for antitrust enforcement and had a lasting impact on the telecommunications industry.

Microsoft. The Microsoft antitrust case, initiated in October 1998, saw the U.S. government accusing Microsoft of abusing its monopoly power in the personal computer operating systems market. The government, represented by David Boies (yes, Theranos David Boies), argued that Microsoft, led by Bill Gates, had engaged in anti-competitive practices to stifle competition, particularly in the web browser market. Gates was famously deposed and shockingly (not really) came away from the deposition looking like an asshole. The government alleged that Microsoft violated the Sherman Act by: Bundling its Internet Explorer (IE) web browser with its Windows operating system, thereby hindering competing browsers like Netscape Navigator, manipulating application programming interfaces to favor IE, and enforcing restrictive licensing agreements with original equipment manufacturers, compelling them to include IE with Windows. Judge Thomas Jackson presided over the case at the United States District Court for the District of Columbia. In 1999, he ruled in favor of the government, finding that Microsoft held a monopoly and had acted to maintain it. He ordered Microsoft to be split into two units, one for operating systems and the other for software components. Microsoft appealed the decision. The Appeals Court overturned the breakup order, partly due to Judge Jackson's inappropriate discussions with the media. While upholding the finding of Microsoft's monopolistic practices, the court deemed traditional antitrust analysis unsuitable for software issues. The case was remanded to Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly, and ultimately, a settlement was reached in 2001. The settlement mandated Microsoft to share its application programming interfaces with third-party companies and grant a panel access to its systems for compliance monitoring. However, it did not require Microsoft to change its code or bar future software bundling with Windows. This led to criticism that the settlement was inadequate in curbing Microsoft's anti-competitive behavior. History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme and Microsoft is doing the exact same bundling strategy again with its Teams app.

Business Themes

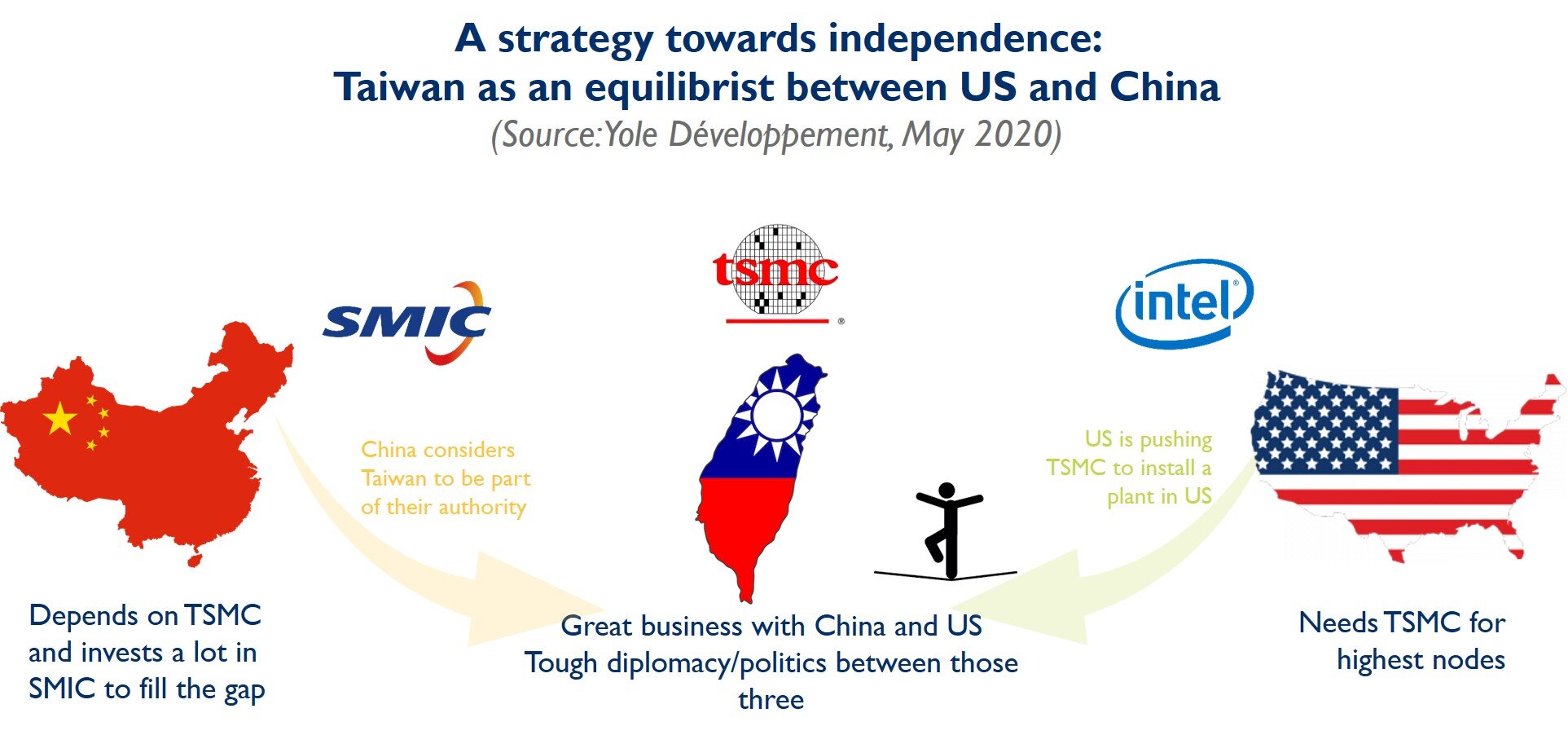

Monopoly Markets. Tepper lays out all of the markets that he believes are monopoly, duopoly, or oligopoly markets. Cable/high speed internet (Comcast, Verizon, AT&T, Charter (Spectrum)) - pretty much the same, Computer Operating Systems (Microsoft) - pretty much the same but iOS and Linux are probably bigger, Social Networks (Facebook with 75% share). Since then Tiktok, Twitter, Pinterest, and Snap have all put a small dent in Facebook’s share. Search (Google), Milk (Dean Foods), Railroads (BNSF, NSC, CSX, Union Pacific, Kansas City Southern), Seeds (Bayer/Monsanto, Syngenta/ChemChina, Dow/DuPont), Microprocessors (Intel 80%, AMD 20%), Funeral Homes (Service Corporation International) all join the monopoly club. The duopoly club consists of Payment Systems (Visa, Mastercard), Beer (AB Inbev, Heineken), Phone Operating Systems (iOS, Android), Online Advertising (Google, Facebook), Kidney Dialysis (DaVita), and Glasses (Luxottica). The oligopoly club is Credit Reporting Bureaus (Transunion, Experian, FICO), Tax Preparation (H&R Block, Intuit), Airlines (American, Delta, United, Southwest, Alaska), Phone Companies (Verizon, Sprint, T-Mobile, AT&T), Banks (JP Morgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup, Wells Fargo), Health Insurance (UnitedHealthcare, Centene, Humana, Aetna), Medical Care (HCA, Encompass, Ascension, Universal Health), Group Purchasing Organizations (Vizient, Premier, HealthTrust, Intaler), Pharmacy Benefit Managers (Express Scripts, CVS Caremark, Optum/UnitedHealthcare), Drug Wholesalers (Cencora, McKesson, Cardinal Health), Agriculture (ADM, Bunge, Cargill, Louis Dreyfus), Media (Walt Disney, Time Warner, CBS, Viacom, NBC Universal, News Corp), Title Insurance (Fidelity National, First American, Stewart, and Old Republic). Since the book was published in 2018, there has been even more consolidation - Canadian Pacific bought Kansas City Southern for $31B, Essilor merged with Luxottica in 2018 in a $49B deal, Sprint merged with T-Mobile in a $26B deal, and CBS and Viacom merged in a $30B deal. Tepper’s anger towards lackadaisical enforcement of antitrust is palpable. He encourages greater antitrust speed and transparency, the unwinding of now clear market consolidating mergers, and the breakup of local monopolies.

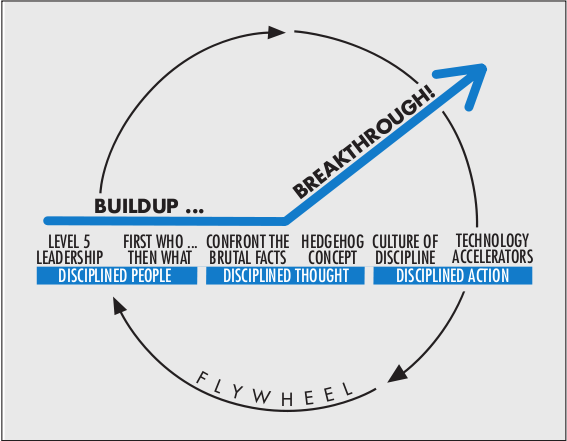

Conglomeration and De-Conglomeration. Market Concentration. The conglomerate boom, primarily occurring in the 1960s, saw a surge in the formation of large corporations encompassing diverse, often unrelated businesses. This era was fueled by low interest rates and a fluctuating stock market, creating favorable conditions for leveraged buyouts. A key driver of this trend was the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950, which, by prohibiting companies from acquiring their competitors or suppliers, pushed them towards diversification through acquiring businesses in unrelated fields. The prevailing motive was to achieve rapid growth, even if it meant prioritizing revenue growth over profit growth. Conglomerates were seen as a means to mitigate risk through diversification and achieve operational economies of scale. Many conglomerates formed that operated across completely different industries: Gulf and Western (Paramount Pictures, Simon & Schuster, Sega, Madison Square Garden), ITT (Telephone companies, Avis, Wonder Bread, Hartford Insurance, and Sheraton), and Henry Singleton’s Teledyne. However, the conglomerate era ultimately waned. The government took a more proactive approach to acquisitions in the late 1960s, curbing the aggressive approaches. The FTC sued Proctor & Gamble over its potential acquisition of Clorox and merger guidelines were revised in 1968, setting out more rules against market share and concentration. Rising interest rates in the 1970s strained these sprawling enterprises, forcing them to divest many of their acquisitions. The belief in the inherent efficiency of conglomerates was challenged as businesses increasingly favored specialization over sprawling, unwieldy structures. The concept of synergy, once touted as a key advantage of conglomerates, came under scrutiny. Ultimately, the conglomerate era was marked by performance dilution, value erosion, and the realization that strong performance in one business did not guarantee success in unrelated sectors.

Industry Concentration. A central pillar to Tepper’s argument that the capitalism game isn’t being played fairly or appropriately, is that rising industry concentration is worrisome and indicative of a broken market system. He uses the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) to discuss levels of industry concentration. According to the Antitrust Division at the DOJ: “The HHI is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm competing in the market and then summing the resulting numbers. For example, for a market consisting of four firms with shares of 30, 30, 20, and 20 percent, the HHI is 2,600 (302 + 302 + 202 + 202 = 2,600). The agencies generally consider markets in which the HHI is between 1,000 and 1,800 points to be moderately concentrated, and consider markets in which the HHI is in excess of 1,800 points to be highly concentrated.” The HHI index is relatively straightforward to calculate. It can be a quick test to see if a potential merger creates a more significantly concentrated market. However, it still falls prey to some issues. For example, market definitions are extremely important in antitrust cases and a poorly or narrowly defined market can cause the HHI to look overly concentrated. In the ongoing Kroger-Albertson’s Merger case, the FTC is proposing a somewhat narrow definition of supermarkets, which excludes large supermarket players like Walmart, Costco, Aldi, and Whole Foods. If Whole Foods isn’t a super market, I’m not sure what is. And sure, maybe they narrowly define the market because Kroger and Albertsons serve a particular niche where substitutes are not easily available. Whole Foods may be more expensive, Aldi may have limited assortment, and Costco portion sizes may be too big. However, if you have a market that has Kroger, Walmart, Costco, Aldi, and Whole Foods serving a reasonable size population, I can almost guarantee the prices are likely to remain competitive. In some cases, high industry concentration does not mean monopolistic behavior. However, it can lead to monopolistic or monopsonistic behavior including: higher prices, lower worker’s wages, lower growth, and greater inequality.

Dig Deeper