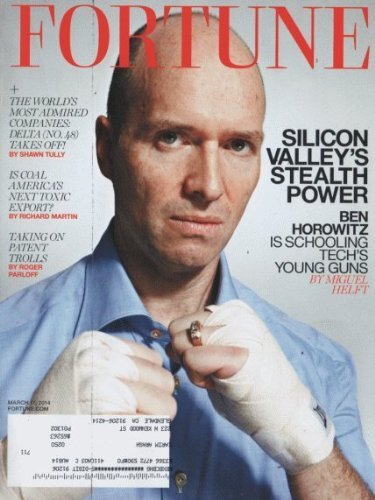

Ben Horowitz, GP of the famous investment fund Andreessen Horowitz, addresses the not-so-pleasant aspects of being a founder/CEO during a crisis. This book provides an excellent framework for anyone going through the struggles of scaling a business and dealing with growing pains.

Tech Themes

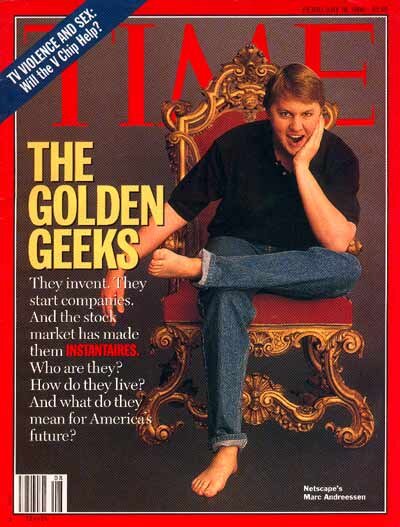

The importance of Netscape. Now that its been relegated to history by the rise of AOL and internet explorer, its hard to believe that Netscape was ever the best web browser. Founded by Marc Andreessen, who had founded the first web browser, Mosaic (as a teenager!), Netscape would go on to achieve amazing success only to blow up in the face of competition and changes to internet infrastructure. Netscape was an incredible technology company, and as Brian McCullough shows in last month’s TBOTM, Netscape was the posterchild for the internet bubble. But for all the fanfare around Netscape’s seminal IPO, little is discussed about its massive and longstanding technological contributions. In 1995, early engineer Brendan Eich created Javascript, which still stands as the dominant front end language for the web. In the same year, the Company developed Secure Socket Layer (SSL), the most dominant basic internet security protocol (and reason for HTTPS). On top of those two fundamental technologies, Netscape also developed the internet cookie, in 1994! Netscape is normally discussed as the amazing company that ushered many of the first internet users onto the web, but its rarely lauded for its longstanding technological contributions. Ben Horowitz, author of the Hard Thing About Hard Things was an early employee and head of the server business unit for Netscape when it went public.

Executing a pivot. Famous pivots have become part of startup lore whether it be in product (Glitch (video game) —> Slack (chat)), business model (Netflix DVD rental —> Streaming), or some combo of both (Snowdevil (selling snowboards online) —> Shopify (ecommerce tech)). The pivot has been hailed as necessary tool in every entrepreneur’s toolbox. Though many are sensationalized, the pivot Ben Horowitz underwent at LoudCloud / Opsware is an underrated one. LoudCloud was a provider of web hosting services and managed services for enterprises. The Company raised a boatload ($346M) of money prior to going public in March 2001, after the internet bubble had already burst. The Company was losing a lot of money and Ben knew that the business was on its last legs. After executing a 400 person layoff, he sold the managed services part of the business to EDS, a large IT provider, for $63.5M. LoudCloud had a software tool called Opsware that it used to manage all of the complexities of the web hosting business, scaling infrastructure with demand and managing compliance in data centers. After the sale was executed, the company’s stock fell to $0.35 per share, even trading below cash, which meant the markets viewed the Company as already bankrupt. The acquisition did something very important for Ben and the Opsware team, it bought them time - the Company had enough cash on hand to execute until Q4 2001 when it had to be cash flow positive. To balance out these cash issues, Opsware purchased Tangram, Rendition Networks, and Creekpath, which were all software vendors that helped manage the software of data centers. This had two effects - slowing the burn (these were profitable companies), and building a substantial product offering for data center providers. Opsware started making sales and the stock price began to tick up, peaking the attention of strategic acquirers. Ultimately it came down to BMC Software and HP. BMC offered $13.25 per share, the Opsware board said $14, BMC countered with $13.50 and HP came in with a $14.25 offer, a 38% premium to the stock price and a total valuation of $1.6B, which the board could not refuse. The Company changed business model (services —> software), made acquisitions and successfully exited, amidst a terrible environment for tech companies post-internet bubble.

The Demise of the Great HP. Hewlett-Packard was one of the first garage-borne, silicon valley technology companies. The company was founded in Palo Alto by Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard in 1939 as a provider of test and measurement instruments. Over the next 40 years, the company moved into producing some of the best printers, scanners, calculators, logic analyzers, and computers in the world. In the 90s, HP continued to grow its product lines in the computing space, and executed a spinout of its manufacturing / non-computing device business in 1999. 1999 marks the tragic beginning of the end for HP. The first massive mistake was the acquisition of Compaq, a flailing competitor in the personal computer market, who had acquired DEC (a losing microprocessor company), a few years earlier. The acquisition was heavily debated, with Walter Hewlett, son of the founder and board director at the time, engaging in a proxy battle with then current CEO, Carly Firorina. The new HP went on to lose half of its market value and incur heavy job losses that were highly publicized. This started a string of terrible acquisitions including EDS, 3COM, Palm Inc., and Autonomy for a combined $28.8B. The Company spun into two divisions - HP Inc. and HP Enterprise in 2015 and each had their own spinouts and mergers from there (Micro Focus and DXC Technology). Today, HP Inc. sells computers and printers, and HPE sells storage, networking and server technology. What can be made of this sad tale? HP suffered from a few things. First, poor long term direction - in hindsight their acquisitions look especially terrible as a repeat series of massive bets on technology that was already being phased out due to market pressures. Second, HP had horrible corporate governance during the late 90s and 2000s - board in-fighting over acquisitions, repeat CEO fiirings over cultural issues, chairman-CEO’s with no checks, and an inability to see the outright fraud in their Autonomy acquisition. Lastly, the Company saw acquisitions and divestitures as band-aids - new CEO entrants Carly Fiorina (from AT&T), Mark Hurd (from NCR), Leo Apotheker (from SAP), and Meg Whitman (from eBay) were focused on making an impact at HP which meant big acquisitions and strategic shifts. Almost none of these panned out, and the repeated ideal shifts took a toll on the organization as the best talent moved elswehere. Its sad to see what has happened at a once-great company.

Business Themes

Ill, not sick: going public at the end of the internet bubble. Going public is supposed to be the culmination of a long entrepreneurial journey for early company employees, but according to Ben Horowitz’s experience, going public during the internet bubble pop was terrible. Loudcloud had tried to raise money privately but struggled given the terrible conditions for raising money at the beginning of 2001. Its not included in the book but the reason the Company failed to raise money was its obscene valuation and loss. The Company was valued at $1.15B in its prior funding round and could only report $6M in Net Revenue on a $107M loss. The Company sought to go public at $10 per share ($700M valuation), but after an intense and brutal roadshow that left Horowitz physically sick, they settled for $6.00 per share, a massive write-down from the previous round. The fact that the banks were even able to find investors to take on this significant risk at this point in the business cycle was a marvel. Timing can be crucial in an IPO as we saw during the internet bubble; internet “businesses” could rise 4-5x on their first trading day because of the massive and silly web landgrab in the late 90s. On the flip side, going public when investors don’t want what you’re selling is almost a death sentence. Although they both have critical business and market issues, WeWork and Casper are clear examples of the importance of timing. WeWork and Casper were late arrivals on the unicorn IPO train. Let me be clear - both have huge issues (WeWork - fundamental business model, Casper - competition/differentiation) but I could imagine these types of companies going public during a favorable time period with a relatively strong IPO. Both companies had massive losses, and investors were especially wary of losses after the failed IPOs of Lyft and Uber, which were arguably the most famous unicorns to go public at the time. Its not to say that WeWork and Casper wouldn’t have had trouble in the public markets, but during the internet bubble these companies could’ve received massive valuations and raised tons of cash instead of seeking bailouts from Softbank and reticent public market investors.

Peactime / Wartime CEO. The genesis of this book was a 2011 blog post written by Horowitz detailing Peacetime and Wartime CEO behavior. As the book and blog post describe, “Peacetime in business means those times when a company has a large advantage vs. the competition in its core market, and its market is growing. In times of peace, the company can focus on expanding the market and reinforcing the company’s strengths.” On the other hand, to describe Wartime, Horowitz uses the example of a previous TBOTM, Only the Paranoid Survive, by Andy Grove. In the early 1980’s, Grove realized his business was under serious threat as competition increased in Intel’s core business, computer memory. Grove shifted the entire organization whole-heartedly into chip manufacturing and saved the company. Horowitz outlines several opposing behaviors of Peacetime and Wartime CEOs: “Peacetime CEO knows that proper protocol leads to winning. Wartime CEO violates protocol in order to win; Peacetime CEO spends time defining the culture. Wartime CEO lets the war define the culture; Peacetime CEO strives for broad based buy in. Wartime CEO neither indulges consensus-building nor tolerates disagreements.” Horowitz concludes that executives can be a peacetime and wartime CEO after mastering each of the respective skill sets and knowing when to shift from peacetime to wartime and back. The theory is interesting to consider; at its best, it provides an excellent framework for managing times of stress (like right now with the Coronavirus). At its worst, it encourages poor CEO behavior and cut throat culture. While I do think its a helpful theory, I think its helpful to think of situations that may be an exception, as a way of testing the theory. For example, lets consider Google, as Horowitz does in his original article. He calls out that Google was likely entering in a period of wartime in 2011 and as a result transitioned CEOs away from peacetime Eric Schmidt to Google founder and wartime CEO, Larry Page. Looking back however, was it really clear that Google was entering wartime? The business continued to focus on what it was clearly best at, online search advertising, and rarely faced any competition. The Company was late to invest in cloud technology and many have criticized Google for pushing billions of dollars into incredibly unprofitable ventures because they are Larry and Sergey’s pet projects. In addition, its clear that control had been an issue for Larry all along - in 2011, it came out that Eric Schmidt’s ouster as CEO was due to a disagreement with Larry and Sergey over continuing to operate in China. On top of that, its argued that Larry and Sergey, who have controlling votes in Google, stayed on too long and hindered Sundar Pichai’s ability to effectively operate the now restructured Alphabet holding company. In short, was Google in a wartime from 2011-2019? I would argue no, it operated in its core market with virtually no competition and today most Google’s revenues come from its ad products. I think the peacetime / wartime designation is rarely so black and white, which is why it is so hard to recognize what period a Company may be in today.

Firing people. The unfortunate reality of business is that not every hire works out, and that eventually people will be fired. The Hard Thing About Hard Things is all about making difficult decisions. It lays out a framework for thinking about and executing layoffs, which is something that’s rarely discussed in the startup ecosystem until it happens. Companies mess up layoffs all the time, just look at Bird who recently laid off staff via an impersonal Zoom call. Horowitz lays out a roughly six step process for enacting layoffs and gives the hard truths about executing the 400 person layoff at LoudCloud. Two of these steps stand out because they have been frequently violated at startups: Don’t Delay and Train Your Managers. Often times, the decision to fire someone can be a months long process, continually drawn out and interrupted by different excuses. Horowitz encourages CEOs to move thoughtfully and quickly to stem leaks of potential layoffs and to not let poor performers continue to hurt the organization. The book discusses the Law of Crappy People - any level of any organization will eventually converge to the worst person on that level; benchmarked against the crappiest person at the next level. Once a CEO has made her mind up about the decision to fire someone, she should go for it. As part of executing layoffs, CEOs should train their managers, and the managers should execute the layoffs. This gives employees the opportunity to seek direct feedback about what went well and what went poorly. This aspect of the book is incredibly important for all levels of entrepreneurs and provides a great starting place for CEOs.