We continue our exploration of Disney’s history with this fascinating book on managing creativity by one of the best to ever do it, Ed Catmull!

Tech Themes

An Unlikely Start. When Pixar began, it did not set out to produce feature length films for children. In fact, it wasn’t even a movie studio. Pixar began as the computer division of George Lucas’s Industrial Light and Magic special effects studio. Following the success of Star Wars, Lucas sought to improve on his amazing special effects, by employing more digital computers. In 1979,Lucas hired Ed Catmull to lead the division, and begin building custom computers for special effects. As Catmull puts it; “Alvy’s team set out to design a highly specialized standalone computer that had the resolution and processing power to scan film, combine special effects images with, live action footage, and then record the final result back onto film. It took us roughly four years, but our engineers built just such a device, which we named Pixar Image Computer.” The name comes from a Pixer (a fake word) and Radar. In 1983, Catmull met a promising Disney Animator named John Lassester, who had just been fired by Disney after pitching his movie idea, Brave Little Toaster. Shortly after he joined Lucasfilm, the Pixar team set a goal to produce an animated short movie at the 1984 SIGGRAPH animation conference. Wally B. debuted and blew people away. Up until then, graphics was done by technology people, and almost never included storytellers and animators. As Walter Issacson pointed out in our January 2020 book, teams with diverse backgrounds, complementary styles, and visionary and operating capacity execute the best.

Exceptional Talent. Although Lasseter was a perfect fit at Pixar, gloom was on the horizon. In 1983, George Lucas divorced his then wife Marcia, which created financial challenges at Lucasfilm. He decided to sell Pixar, and courted buyers including Phillips, which wanted to use Pixar’s rendering capabilities for CT scans and MRIs, and General Motors which wanted to use its technology for modeling objects. Neither party wanted the team, and they definitely didn’t want to make animated feature films. Steve Jobs also took a look at the business, but couldn’t pull the trigger because of the immense pressure he was under at Apple (which ultimately led to his ousting). It wasn’t until almost 18 months later, and after founding NeXT, that Jobs was ready, and on January 3rd 1986, Jobs acquired Pixar for $5M. Pixar went about trying to sell their high-tech computer for $122,000 a piece, but couldn’t find many buyers (only 300 were sold). They continued making short videos and were even nominated for an Academy Award in 1987 for Luxo, Jr, a short film about a lamp. But the Company was losing tons of money, and by 1987, Jobs had sunk $54m into the company with little to show for it. The Company decided to pivot from selling computers, to making animated commercials for brands, but it didn’t produce enough cash flow to cover costs. Between 1987 and 1991, Jobs tried to sell Pixar three times: “When Microsoft offered $90 million for us he walked away. Steve wanted $120 million, and felt their offer was not just insulting but proof they weren’t worth of us. The same thing happened with Alias, the industrial and automotive design software company, and with Silicon Graphics…His reasoning was this: if Microsoft was willing to go to $90 million, then we mmust be worth hanging on to.” Jobs realized that Pixar had exceptional talent, and that it needed more time to achieve its vision. The combination of Lasseter, Catmull, and Jobs was truly unstoppable. These small acquisitions are reticent of IAC’s acquisition of College Humor, which came with a small video company called Vimeo. Sometimes these small acquisitions that are filled with creative talent can produce unbelievable results.

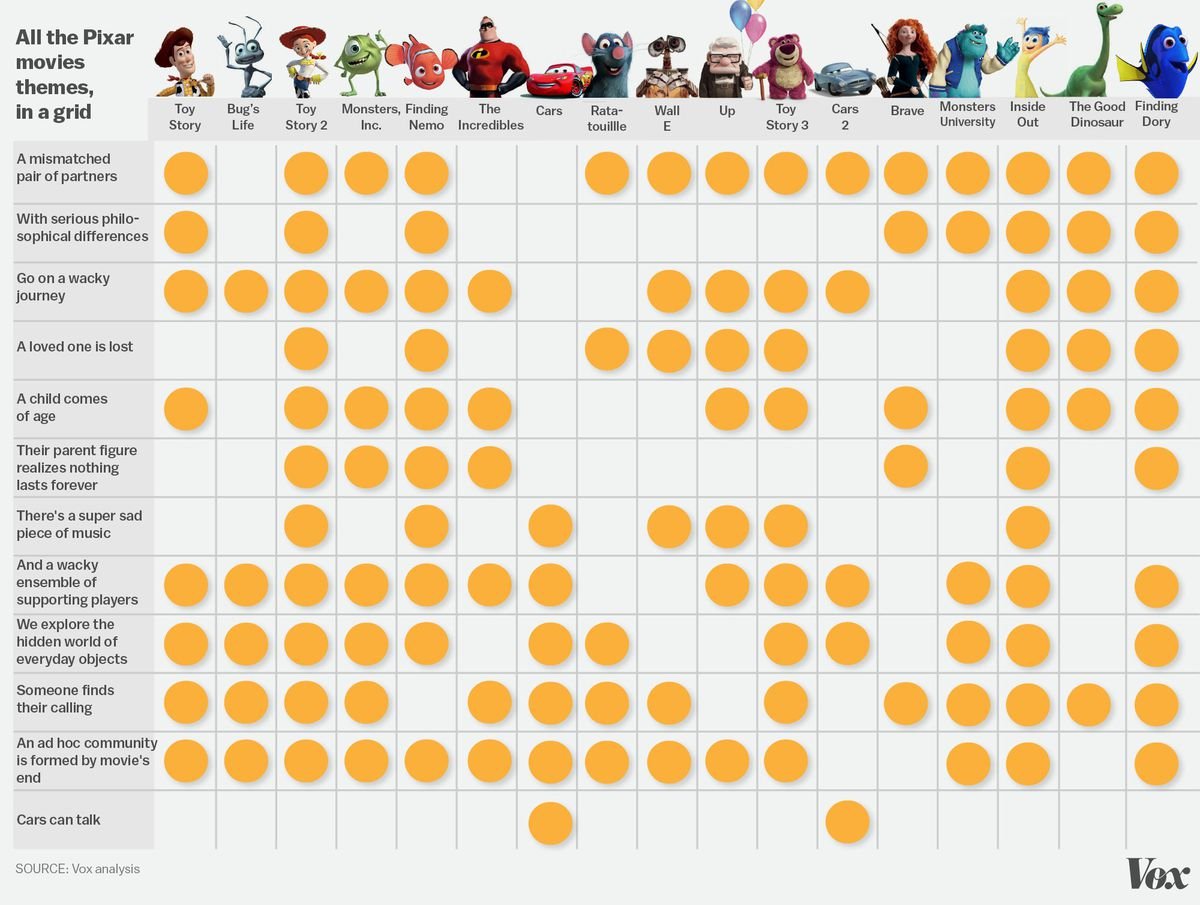

Unstable Ground. Its incredibly daunting to create something from nothing, whether its a company or a film. You feel unsure of yourself and your ideas, not knowing the right approach, wondering if your time is being used wisely. Managing in this environment requires: Frank talk, spirited debate, laughter, and love. To accomplish this list of positive tactics, Pixar created the Braintrust, a group of writers, directors, and creatives that could give early feedback to new films. The braintrust is made up of “People with a deep understanding of storytelling and, usually, people who have been through the process [of making a movie] themselves. The other important difference is the Braintrust has no authority, Directors do not have to listen to the feedback. The Braintrust has empathy for the Director. It knows: “[Mistakes] are an inevitable consequence of doing something new (and, as such, should be seen as valuable; without them, we’d have no originality.” As an example of this unstable ground, Catmull recalls the development of Monsters, Inc. Originally, Pete Docter (now CEO of Pixar), developed an idea that “revolved around a thirty-year-old man who was coping with cast of frightening characters that only he could see. His mom gives him a book with some drawings in it that he did when he was a kid. He doesn’t think anything of it, and he puts it on the shelf, and that night, monsters show up. And nobody else can see them. They follow him to his job, and on his dates, and it turns out these monsters are all the fears the he never dealt with as a kid.” Over a period of five years, Monsters Inc changed multiple times, but the ethos of “Monsters are real, and they scare kids for a living,” never changed. When approaching a creative project, things meander and wander, where they start is not normally where they end. Catmull believes: “Originality is fragile. Rather than trying to prevent all errors, we should assume, as is almost always the case, that our people’s intentions are good and that they want to solve problems. Give them responsibility, let the mistakes happen, and let people fix them.” New ideas are hard enough, you need to nurture and support them, whichever direction they go, to get to a high quality finished product.

Business Themes

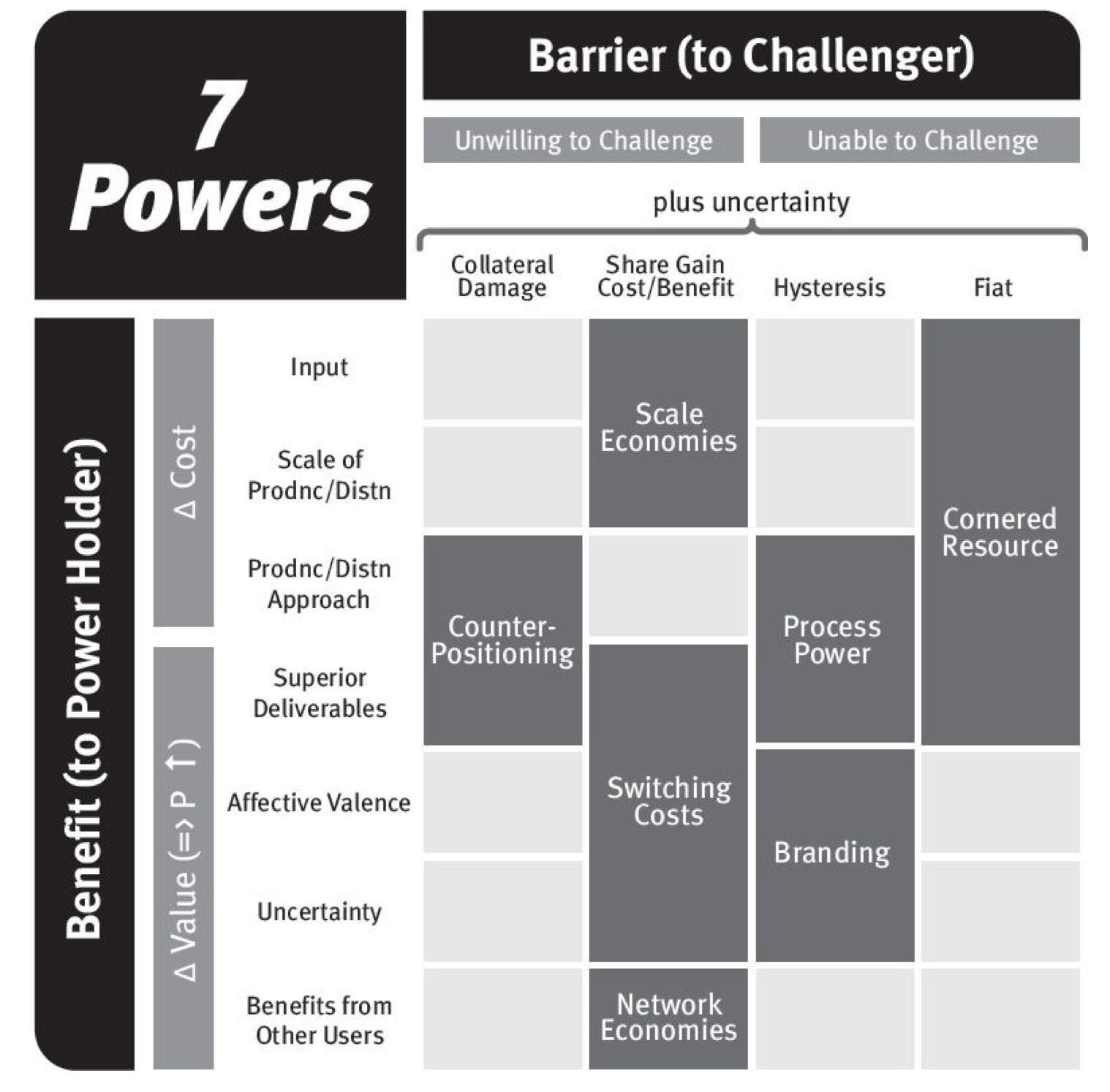

Balance and Feeding the “Beast”. After Pixar was acquired by Disney, Catmull began hearing the phrase, “You’ve got to feed the Beast.” He was referring to “any large group that needs to be fed an uninterrupted diet of new material and resources in order to function. Following the success of the Lion King in 1994, The bureaucracy of Disney grew to the point that the process of making, marketing, and distributing films engulfed the creative process, leading to pressure for quick and fast success. You “feed the Beast, to occupy its time and attention, putting its talents to use. [But] success only creates more pressure to hurry up and succeed again. Which is why at too many companies, the schedule (that is, the need for product) drives the output, not the strength of the ideas at the front end.” In order to manage this all-consuming Beast, organizations must seek balance. You have to manage the goals of all parties involved, while giving time and energy to the best most creative ideas in the company. “The key is to view conflict as essential. A good manager must always be on the look for areas in which balance has been lost.” Its not as easy as it sounds to achieve balance, but experience is a helpful guide. It takes a constant focus and a subtle understanding of an organization’s psychology.

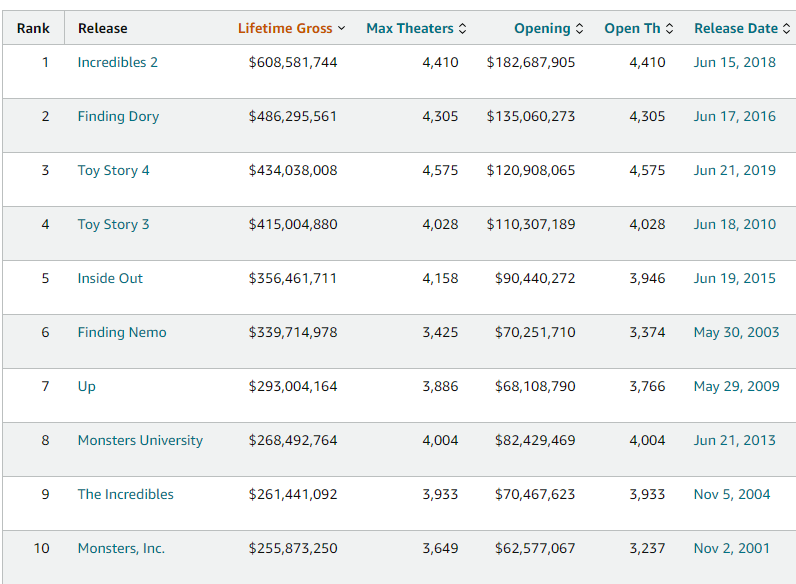

Pixar-Disney: A Love Hate Relationship. In January 2006, Disney acquired Pixar for $7.4B, a fairy-tale ending. But it wasn’t an easy beginning. After the incredible success of Toy Story, Pixar negotiated a five picture deal with Disney to handle its distribution, whereby Pixar would get an equal cut as Disney. Pixar delivered incredible films for Disney including: A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc, and Finding Nemo. But all was not well in the partnership. Following a series of public slights at eachother, Steve Jobs and Michael Eisner essentially put the kaibosh on negotiations, both feeling they were the more important partner in any deal. With Cars and the Incredibles already in development, Disney and Pixar called off their partnership in 2004. This decision was the beginning of the end for Disney CEO, Michael Eisner, who resigned in the fall of 2005. Following his departure, Iger was named CEO, and set about repairing the broken relationship with Steve Jobs and Pixar. We have discussed the deal in length, but one of the subtle features was that Ed Catmull and John Lasseter would become head of Disney Animation, on top of Pixar. Disney animation was struggling. In the eyes of Circle 7 Studio Head Andrew Millstein, “Our filmmakers had lost their voices. It wasn’t that they had no desire to express themselves, but there was an imbalance of forces in the organization - not just within it, but between it and the rest of the corporation - that diminished the vailidity of teh creative voice. The balance was gone.” Wildly, the Pixar team notes that there were three sets of notes for a film: one from the development department, one from the head of the stuiod, and a third from Michael Eisner himself. This feedback was often conflicting and more “you must” then “you should think about.” When Catmull realized the challenge, they created a braintrust purposefully for Disney Animation, called the Story Trust. The first two meetings (for Meet the Robinsons, and American Dog - later Bolt) were unimpressive, and lacked the dynamism of true brain turst meetings. The Directors admitted they were afraid to give negative feedback to colleagues so publicly. Over time though the meetings took on more intensity, and a few years after the merger, Disney Animation produced its first successful movie in a while, Tangled. This was quickly followed by Wreck-it Ralph, and Frozen, and Disney Animation was back on track.

Notes Day. After many years of leading Pixar, Catmull realized that Pixar had become much larger, and: “More and more people had begun to feel that it was either not safe or not welcome to offer differing ideas.” The feeling of complacency was also manifesting in three real business problems. Production costs were rising, external economic forces were hitting the business, and a core tenant of the culture (good ideas can come from anywhere) was under attack. To remedy this onslaught of challenges, Pixar created Notes Day. The company created a digital electronic suggestion box where people could submit discussion topics that would help Pixar run more efficiently, with more innovation. They wittled down 4,000 suggesstions to 120 core topics. A handful of employees volunteered to be facilitators and were coached on how to keep meetings on track. The day started with an all-hands where John Lasseter admitted some personal shortcomings - he had been splitting time between Pixar and Disney and people didn’t like it and he frequently carried emotion from one meeting into the next, which confused employees and made employees more emotional. Then participants went to departmental meeting about efficiency, then broke into blocks of 90 minute sessions. At the end of each session - employees could fill out red forms for proposals, blue forms for brainstorms, yellow forms for best practices. The forms asked various questions about benefits to Pixar, how they could become a reality, why the idea was worth pursuing, and who should own the proposal. Notes Day was a cathartic day for employees, who shared feelings and emotions with eachother across functions and working groups. Catmull believes that Notes Day succeeded because there was a clear and focused goal (efficiency/candor), it was championed by senior management, and it was led from within, by individuals who volunteered to run sessions. The whole day mirrored the Kaizen process that was popularized by the Japanese auto-makers after W.E. Deming brought the practices to Japan. Although it was originally a World War II approach under the Training Within Industry job method, Kaizen was key to the Just-in-time manufacturing process used at Toyota. Feedback is critical to business success. Notes Day and Kaizen are great examples of the benefit of focused small improvements driven by passionate employees with great ideas.

Dig Deeper