This month we jump back to an older strategy book to think about pricing, partnerships, and negotiations.

Tech Themes

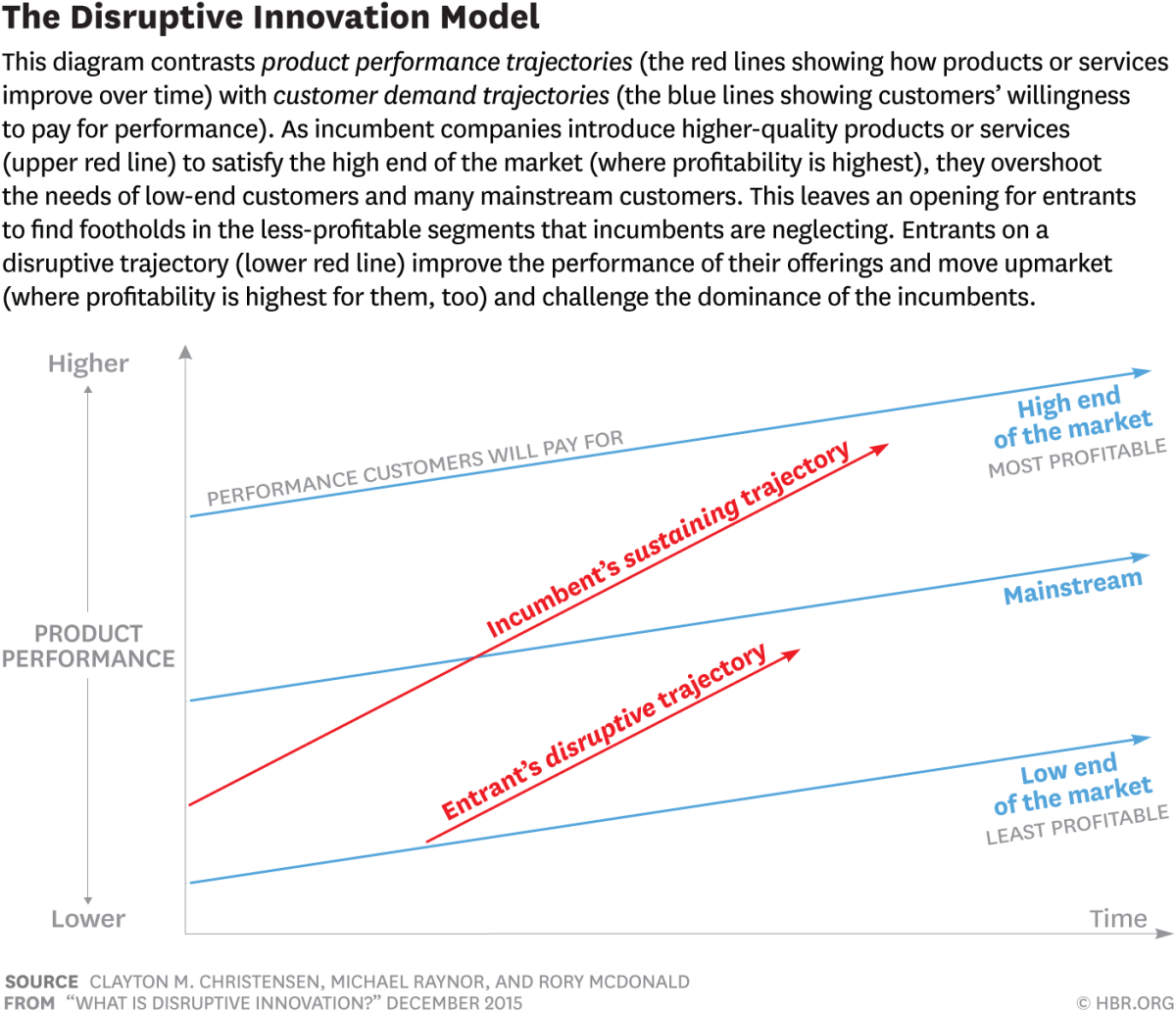

Pricing Printers Poorly. The late-80’s printer aisle looked like trench warfare. There were three types of desktop printers: Dot-matrix (low-end), ink-jets (mid-tier), and laser printers (high-end). The laser segment had the highest prices, best margins, and was growing the fastest. Epson, normally a dot-matrix manufacturer, decided it should enter the laser segment with a competitively priced product, the EPL-6000. One week later, Hewlett‑Packard came out with a printer priced signficantly below Epson’s EPL-6000. Epson further cut price in response. Although Epson gained market share, the damage was done: hardware profits collapsed, and suppliers shifted to a razor-and-blades model, where ink or toner carried gross margins of 60 % or more. But because pricing had come down across the low-end, mid-tier, and high-end, ink-jets started to overtake dot-matrix sales - a better printer for a similar price to a dot-matrix a few months ago. Epson had completely screwed over the segment it was most dominant in by introducing a new, effective competitor. “What was Epson’s mistake? It misunderstood the Scope of the printer game. By treating the laser printer game as separate from the dot-matrix printer game, Epson failed to see that low-price entry into the laser segment could jeopardize its core business.” Epson eventually discovered the peril of winning the wrong battle.

Bidding. In 1984, the FCC divided the country up into 306 separate markets and gave two cellular licenses to each market. Craig McCaw wanted a national cellular footprint before anyone else and went around buying up as many licenses as he could. Lin Broadcasting owned plum metro licenses—Los Angeles, Dallas, New York—that would knit perfectly into McCaw’s West‑Coast empire. In 1989, he made a hostile bid for LIN, conditional on LIN removing the poison pill anti-takeover clause in its shareholder rights plan. Poison Pill’s generally allow companies to issue extreme amounts of shares to dilute a potential acquirer’s interest, thereby making it uneconomic to buy shares in the company. BellSouth, already Lin’s roaming partner, had already crashed the party with a “white‑knight” merger plan and a special $40 dividend, arguing that its investment‑grade balance sheet trumped McCaw’s bidding frenzy. The challenge for BellSouth, was that McCaw had more aggresssive future assumptions for the value of Points of Presence (POPs, or consumers), and thus could justify a much higher bid than BellSouth. BellSouth saw an opportunity to “engage” in the bidding process, but only if LIN agreed to give it a $54m fee and cover $15m of BellSouth’s expenses. When McCaw raised his bid, LIN increased BellSouth’s expense cap to $25m. McCaw, wanting to move quickly to get LIN’s assets and aware of BellSouth’s lack of real interest in acquiring the company, quietly paid BellSouth $26m to stop bidding. McCaw then increased his bid to $6.3B (up from $5.85B) and won the deal. The takeaway here is that BellSouth understood there was some easy money to be gained by entering the bidding process. If it won at a fair price, it would be happy, if not, it would get $75m cash for doing a small amount of work. McCaw also understood that there weren’t any real rules governing BellSouth’s bid and that any payment between parties would be governed by contract law, avoiding any potential antitrust issues. A similar dance played out on Texas’ coast. Corpus Christi’s ABC, NBC, and CBS affiliates—founded decades earlier by local entrepreneurs who treated broadcasting like a civic duty—banded together in 1993 to demand per‑subscriber fees from cable giant TCI. John Malone, ever the game theorist, yanked their signals, flooded the market with distant‑signal substitutes, and quietly negotiated bundled carriage rights in nearby Beaumont before the stations blinked. When one of the entrepreneurs who owned a Beaumont station offered its signal for free, TCI refused. Here, TCI was linking the Beaumont decision to the Corpus Christi decision. By not carrying Beaumont, he was signaling that “how you play me in one city will impact how I do business with you in another.” The DOJ later sued the three broadcasters for collusion, but Malone still walked away having proven that controlling the pipe gives you leverage even when you’re shut out of content. In 2023, when carriage talks collapsed, Charter yanked ESPN and 17 other Disney channels from 14 million Spectrum homes, betting that broadband stickiness outweighed sports FOMO. Disney finally folded, granting free ad‑tier Disney+ access to Spectrum subs—a Malone‑esque outcome.

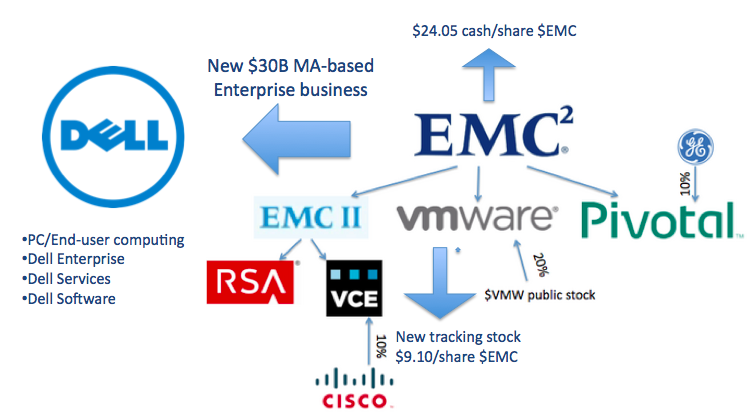

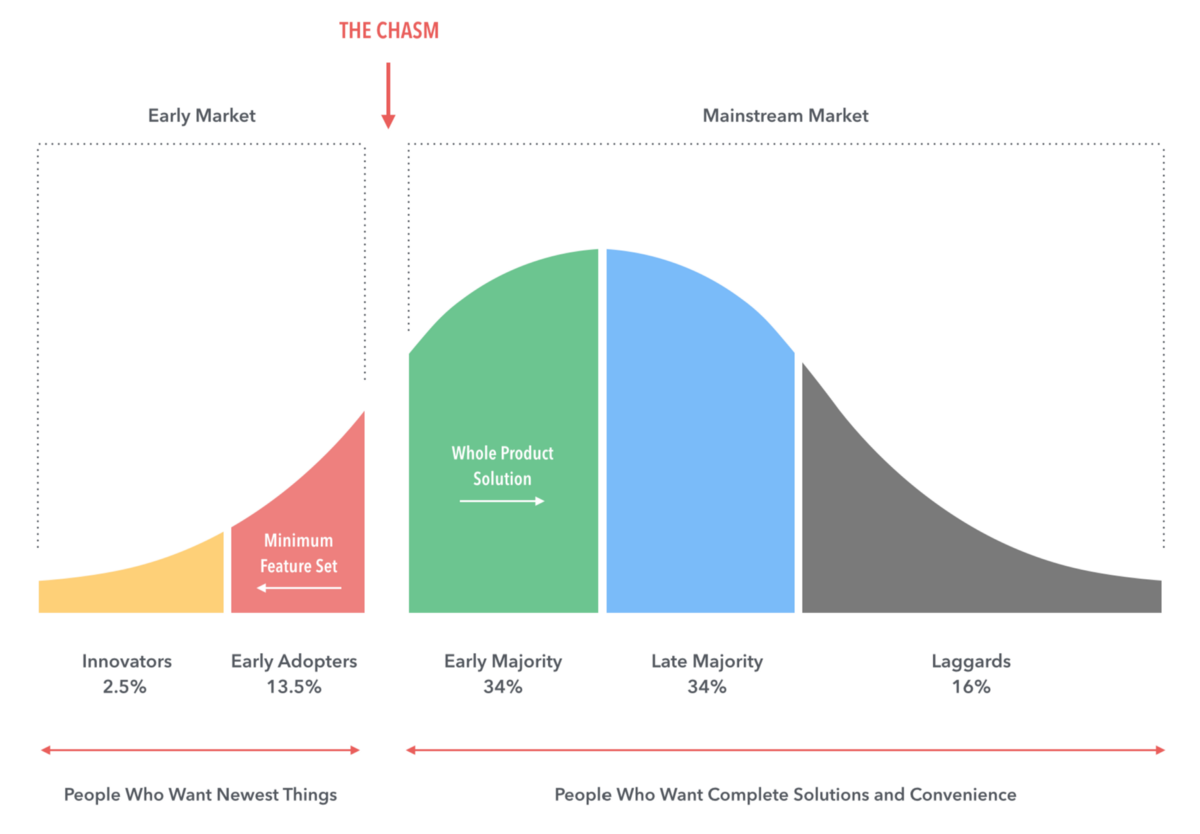

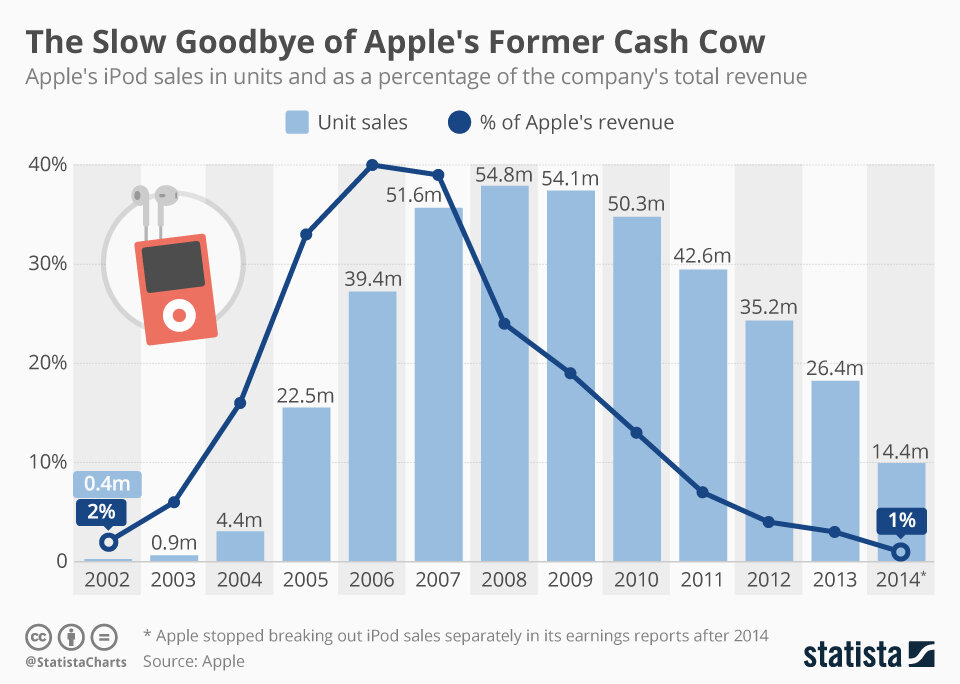

Cheap Complements and Cheap Competition. When Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins launched the 3DO Interactive Multiplayer in 1993, he flipped the console model on its head: keep license fees tiny so developers flood the platform, outsource hardware to Panasonic and GoldStar, and collect a royalty on every game sold. Developers indeed piled in—over 300 titles were announced within 18 months—but the box debuted at a prohibitive $699, three times a Super NES. Consumers passed, inventories ballooned, and retailers slashed shelf space, proving that abundant complements can’t rescue a core product priced for plutocrats. Worse, the royalty stream never matured: with a sub‑million installed base, even best‑selling games shipped under 50k units. By 1996, Hawkins shuttered 3DO hardware, pivoted to software, and lost the ecosystem he had courted. Co‑opetition’s moral: complements add value only when they multiply an affordable core, not when they subsidize an unaffordable one. Apple’s $3,499 Vision Pro dazzles developers yet risks 3DO déjà vu: a high‑end box in search of an installed base big enough to justify killer apps. It seems like there isn’t actually a market there after all. Big Tech’s co‑opetition looks like a rotating tag‑team match: Apple and Google split roughly $20 billion a year in Safari search‑rent—cash Apple pockets while Google keeps iPhone eyeballs—yet the same pact boxes Microsoft’s Bing out of mobile search entirely. Microsoft struck back in 2023 by wiring OpenAI’s GPT‑4 into Bing Chat, forcing Google to scramble with Bard (now Gemini); each new model is less about revenue today than denying the other a toehold in AI mindshare. And sometimes a “friendly” move for one is a gut punch for another: Apple’s App‑Tracking‑Transparency switch won plaudits for privacy but wiped an estimated $12 billion off Meta’s 2022 ad revenue, reminding every platform that a partner today can set the rules tomorrow.

Business Themes

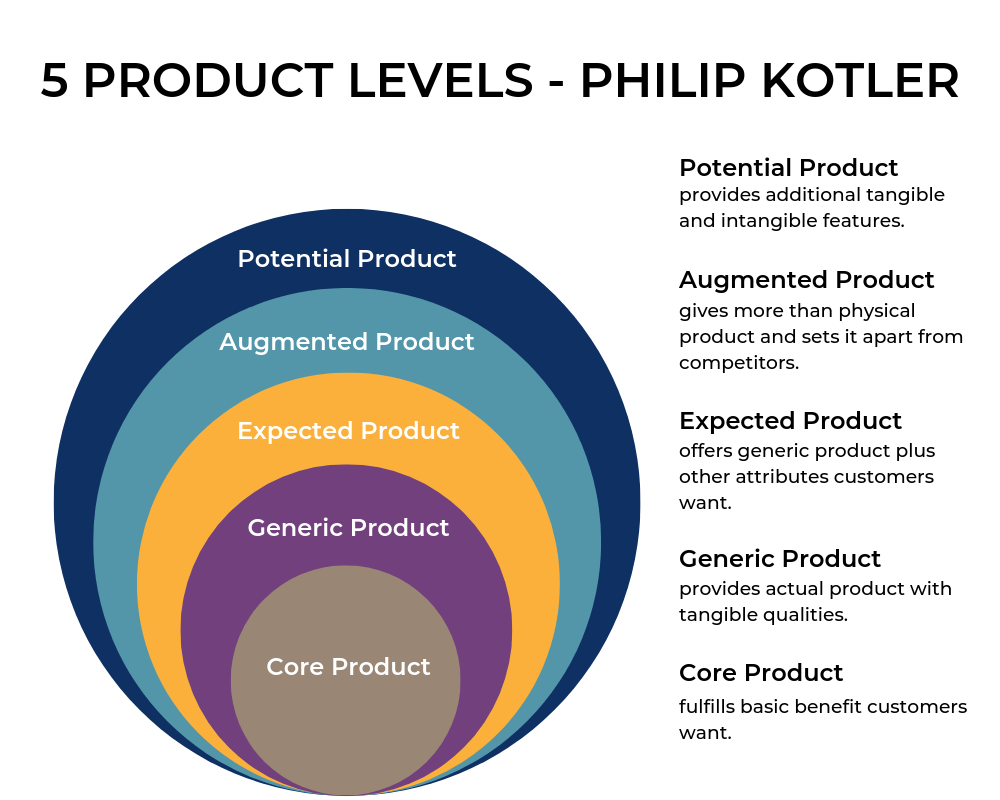

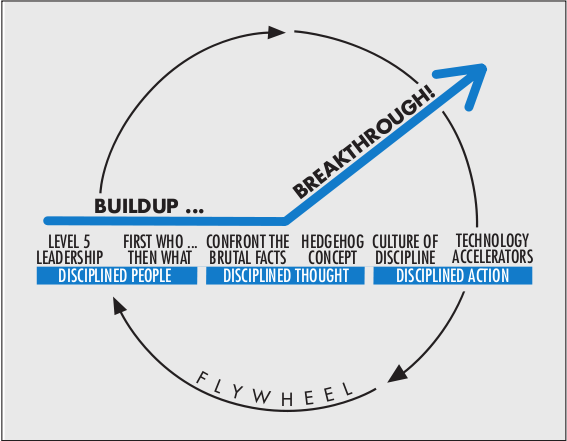

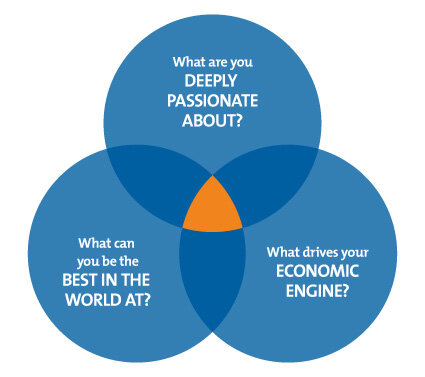

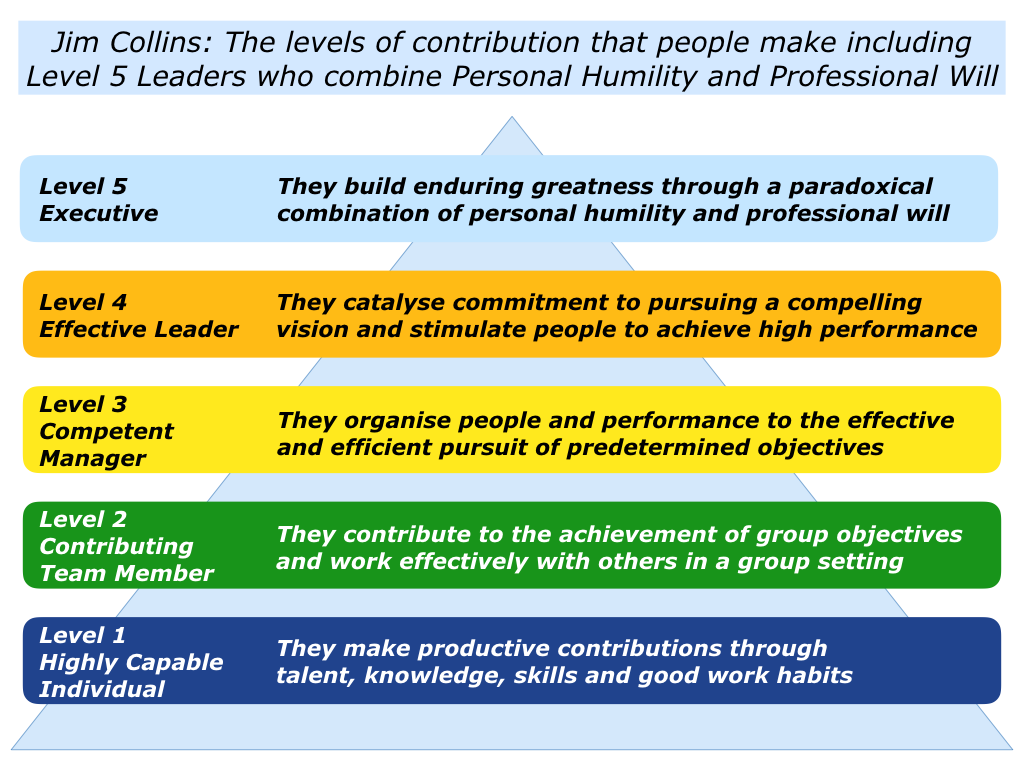

PARTS. Players, Added Value, Rules, Tactics, Scope. Players - List every party that can affect the game—not just obvious competitors but suppliers, complementors, customers, regulators, and would‑be entrants. Brandenburger and Nalebuff call this the “value net.” Miss a player and you misprice your leverage: Epson forgot ink suppliers; Trip Hawkins forgot retailers. Added Value - Quantify how much value the game loses if you step out. Holland Sweetener added so little that NutraSweet could cut price to drive it out. Your bargaining power equals your added value, nothing more. Rules - These are the formal and informal contracts that shape payoffs—patents, standards, MFN clauses, or even industry norms. Changing a single rule (e.g., allowing distant‑signal import in Corpus Christi) can flip winners and losers overnight. Tactics - Moves and countermoves that alter perceptions or hide true intentions: McCaw’s escalating bids signaled resolve; BellSouth’s dividend sweetener signaled financial strength. In judo strategy, feints and timing matter as much as raw force. Scope - Decide which arenas the game covers—geography, product lines, time horizon. Sega narrowed scope to teens; Ryanair to short‑haul cheap UK-Ireland flights. Expanding or shrinking scope can turn a losing game into a winning one.

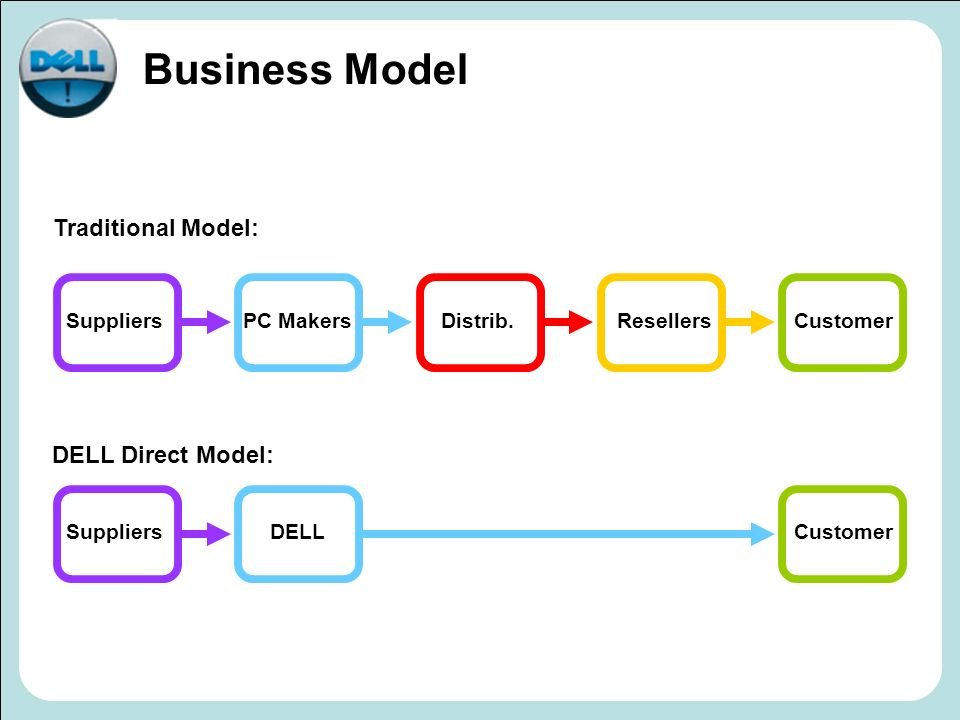

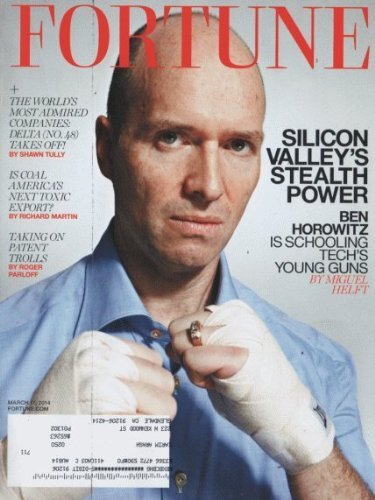

Added Value Reduction. Added value equals “pie with you” minus “pie without you.” Holland Sweetener stormed NutraSweet’s European aspartame stronghold in 1987, hoping to undercut Monsanto’s $70‑per‑pound monopoly. NutraSweet responded by chopping price to $22 and locking Coke and Pepsi into long‑term supply deals. Consumers enjoyed lower prices, but Holland’s new plant hemorrhaged cash and eventually shut down. The pie grew, yet Holland’s slice was negative—a textbook case of creating consumer surplus you can’t capture. IBM managed the opposite trick. Its open‑architecture PC spawned an army of Compaq‑ and Dell‑clones that used reverse‑engineered BIOS chips to deliver 95 % of the function at 60 % of the price. IBM had given up its added value by going both open and outsourcing the manufacturing of the computers, leaving very little IP or value add (outside of brand) to be monetized. By 1990 IBM’s own share of the “IBM‑compatible” market had cratered, and the company ultimately exited retail PCs, conceding de facto standards to the very cloners it had empowered. When your absence barely dents the ecosystem, your added value rounds to zero. OpenAI’s proprietary GPT models generate a lot of value, but Meta’s open-source Llama models enable startups to create custom copilots at near-zero licensing costs, potentially eroding GPT’s pricing umbrella much as Holland Sweetener eroded NutraSweet. Right now, Llama models are just not even close to as good as OpenAI’s models, so up to this point there has been no price erosion. However, price erosion may be the ultimate goal of Mark Zuckerberg, create an open, cheap, cost-competitive model that becomes a no brainer standard and hurts OpenAI’s position with proprietary models. Zuck knows that chatGPT is taking away device time from Instagram and see it as a long-term threat. The pie grows; who keeps the surplus is still up for grabs.

Playing Judo. Sega entered 1990 with 6 % U.S. console share; Nintendo held 94 %. Instead of matching Nintendo’s kids‑friendly catalog, Sega leaned into a teen demographic with Sonic the Hedgehog, faster 16‑bit hardware, and cheeky ads (“Genesis does what Nintendon’t”). Nintendo rushed the Super NES and loosened violence taboos, but by 1994 share was near‑parity. Eventually Nintendo’s stronger software pipeline reclaimed leadership, Sega exited hardware in 2001, and the market stabilized with clearly segmented audiences—a judo bout where the lighter fighter scored enough points before the heavyweight regained footing. Europe’s skies offer another judo masterclass. Ryanair slashed Dublin‑London fares from $150 to under $100 in 1991, betting that a no‑frills model, 30‑minute turnarounds, and a single 737 fleet would lure new flyers instead of stealing British Airways’ elite road‑warriors. BA could have matched fares system‑wide and bled billions; instead, it ceded price‑sensitive segments while defending long‑haul premium cabins. Today, Ryanair ferries more passengers than any other European airline, yet BA still dominates trans‑Atlantic business class. Sometimes, yielding the mat where you’re weakest is how you keep the championship belt.

Dig Deeper