This month we learn about the explore popular productivity book Deep Work, by Cal Newport, a professor of theoretical computer science at Georgetown.

Tech Themes

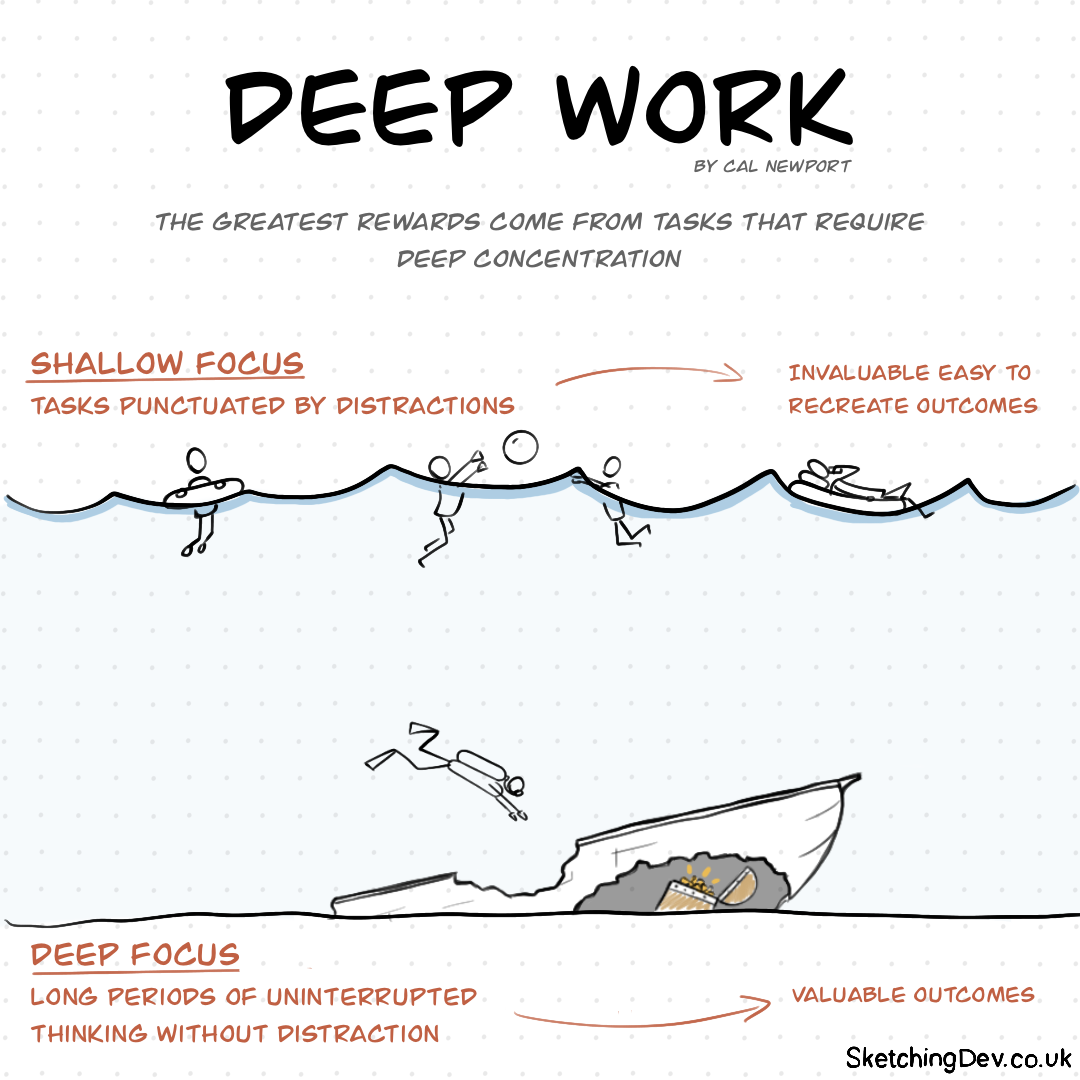

Deep vs. Shallow. Just like Lady Gaga and Bradley Cooper, we, too, are trying to avoid the shallow. Newport starts his book with an overview of Deep Work compared to Shallow Work. Deep Work is focused, undistracted efforts at achieving the peak of your abilities. On the other hand, Shallow Work includes small, logistical tasks that the brain does not need to be entirely active to solve. Newport argues that more time should be spent in Deep mode. It leads to greater productivity and offers a way for individuals to differentiate themselves with the quality of work they do. In Newport's mind, the distracted Tiktok-obsessed world we currently inhabit is only getting more Shallow, so embracing Deep Work is the only way to survive. Shallow Work tends to involve lots of context switching from Task A to Task B. When this context-switching is repeated incessantly throughout the day, our ability to focus on anything diminishes, and we can end up in a permanent state of shallowness.

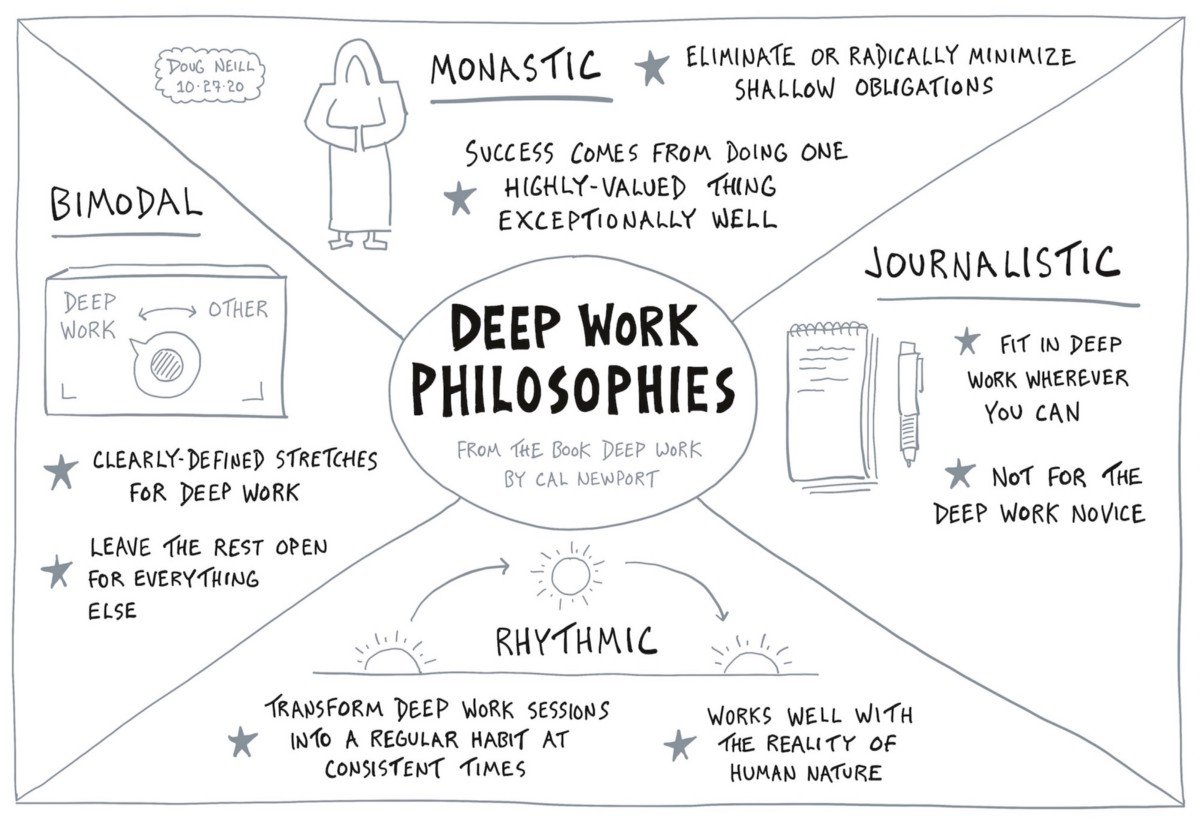

Deep Styles. Newport believes there are four core styles of Deep Work: Monastic, Bi-modal, Rhythmic, and Journalistic. The Monastic philosophy of Deep Work tries to completely eliminate all distractions. An example of Monastic Deep Work is famed computer science professor and Turing award winner Donald Knuth. Knuth does not have an email address. As he explains: "I have been a happy man ever since January 1, 1990, when I no longer had an email address. I'd used email since about 1975, and it seems to me that 15 years of email is plenty for one lifetime. Email is a wonderful thing for people whose role in life is to be on top of things. But not for me; my role is to be on the bottom of things. What I do takes long hours of studying and uninterruptible concentration. I try to learn certain areas of computer science exhaustively; then I try to digest that knowledge into a form that is accessible to people who don't have time for such study. On the other hand, I need to communicate with thousands of people all over the world as I write my books. I also want to be responsive to the people who read those books and have questions or comments. My goal is to do this communication efficiently, in batch mode --- like, one day every six months." Clearly, the monastic state tries to maximize deep work by shutting everything else out. The Bi-Modal philosophy asks the studier to program stretches of life wholly dedicated to Deep Work. Newport uses famous Penn psychology professor Adam Grant, as an example. Grant batches all of his teaching in the fall and all of his research in the spring. This schedule allows him to flip between modes into excellent-teacher Adam and excellent-researcher Adam. In these states, he's entirely dedicated to being the best at each subdomain, providing simplicity, clarity, and purpose to his routines and focus. Rhythmic philosophy entails finding certain times of day to work in stretches of Deep Work. This approach is the most accessible style of Deep Work for people who don't control their schedules. Newport recommends you plan out a week's worth of Deep Work in regular chunks to establish a routine for getting your mind ready to "Go Deep." The last Deep Work mode, the Journalistic philosophy, may be the most challenging style but can have incredibly intense effects. Newport gives Walter Issacson as an example here: "It was always amazing … he could retreat up to the bedroom for a while, when the rest of us were chilling on the patio or whatever, to work on his book … he'd go up for twenty minutes or an hour, we'd hear the typewriter pounding, then he'd come down as relaxed as the rest of us … the work never seemed to faze him, he just happily went up to work when he had the spare time." Find a philosophy that works for your current work structure!

Busyness != Productivity. In today's corporate world, many people equate busyness with productivity. Have I been sending and receiving emails all day? Have I been in meetings? Have I completed five zoom calls? These all feel vaguely productive, or maybe they don't. But either way, they take up large portions of our day. One only has to look at the hilarious new trend of young employees at mega-tech companies posting about their busy days doing what amounts to 3 hours of work while being spoiled by ridiculous offices and employee perks. Maybe this is why Facebook and Google have recently publicly told employees that their organizations are not very productive. Zuckerberg went as far as to say: "Realistically, there are probably a bunch of people at the company who shouldn't be here." Sundar Pichai created a "Simplicity Sprint "week to identify ways to make Google's 174,000 employees more productive. The world may be in for a more focused, intensely productive time with an imminent recession looming. Maybe that is why so many great companies are borne out of times of trouble?

Business Themes

Think Weeks and Unconcious Processing. Bill Gates is famous for taking two weeks a year completely off to set new directives for his life and professional work. We covered this in our June 2021 book regarding information overload in investing. Newport definitely likes the idea of Think Weeks - encouraging people to find separate locations from home or work to build creative momentum for the week. Individuals can also take some grand action, like traveling to a remote place or paying a significant sum for specialized accommodation to signal the importance of the work they are about to attempt. Newport also dives into the idea of unconscious processing or a work shutdown. Newport argues that downtime aids insights, helps recharge the energy needed to work deeply, and pushes us to focus only on necessary things (i.e. that nighttime email responses are usually not super important).

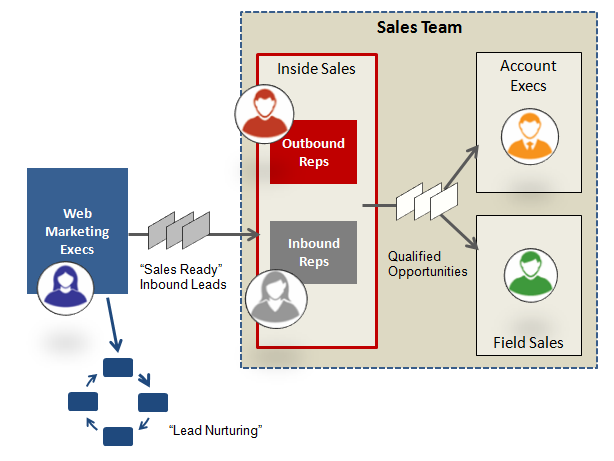

Four Disciplines of Execution (4DX). To help people in their Deep Work journies, Newport introduces us to the Four Disciplines of Execution (4DX), a framework created by the FranklinCovey company for helping companies work better. FranklinCovey is the business associated with Stephen Covey, and his highly successful 7 habits of Successful People and First Things First. His son Sean Covey, wrote and popularized 4DX. The four disciplines espoused by the framework are: (1) Focus on the Wildly Important, (2) Act on Lead Measures, (3) Keep a Compelling Scoreboard, and (4) Create a Cadence of Accountability. Clearly, the first discipline focuses on identifying the significant goals we want to achieve. The second discipline is a bit more nuanced and prompts us to think more about the inputs to success rather than the success itself. As an example, a company might have a revenue target for the year, but that target could be broken down into simple actions by the sales team to reach out to customers, understand use cases, and position the company's product to help. Discipline 2 argues that we should focus on these leading indicators of success rather than revenue achievement itself. The third discipline is about creating consistency and identifying success. Jerry Seinfeld offers a great example of this practice: "He [Jerry Seinfeld] told me to get a big wall calendar that has a whole year on one page and hang it on a prominent wall. The next step was to get a big red magic marker. He said for each day that I do my task of writing, I get to put a big red X over that day. 'After a few days you'll have a chain. Just keep at it and the chain will grow longer every day. You'll like seeing that chain, especially when you get a few weeks under your belt. Your only job next is to not break the chain.' 'Don't break the chain,' he said again for emphasis." This advice likely explains the phenomenon of maintaining Snapchat streaks at all costs. The fourth discipline is about establishing accountability for achieving the goals set out during the previous week. FranklinCovey insists that you hold yourself accountable each week. Hopefully, all that's needed is a 15-minute scheduled window to see your progress. The 4DX method is straightforward, clear, and helpful for executing any goal.

Amp it Up. In the spirit of next month's TBOTM, let's talk about amping up the intensity of our Deep Work. Newport discusses the early and incredible success of Teddy Roosevelt in what seemed like everything he tried. As one blogger notes: "While at Harvard, TR developed an intense study or "deep work" attitude. He would schedule every minute of his day including every activity, meal breaks, and classes. Any "spare time" was slated for study - study that did not include daydreams, sips of tea or any sign of indecision. He focused, without breaks, an intense frenzy of concentrated energy." As BusinessInsider notes, the way to incorporate this into our lives is by: "Newport says one way to incorporate rewarding deep work into your life is 'to inject the occasional dash of Rooseveltian intensity into your own workday.' This entails selecting a high-priority task, estimating how much time it would normally take you, and then creating a deadline well below the typical allotted time." Newport, a theoretical computer scientist, has a formula for how to describe this strategy: Quality Work (QW) = time Spent x Intensity. Quality work therefore does not always need to be achieved through laboring hours but can instead be supplemented with blistering intensity and focus. How do you achieve this superior intensity? There is no theory for becoming a more intense worker, but Newport believes that work intensity is a muscle that can be honed over time with more and more efforts of intense, Deep Work.