We dive into everyone’s favorite topic - Health Insurance!

Tech Themes

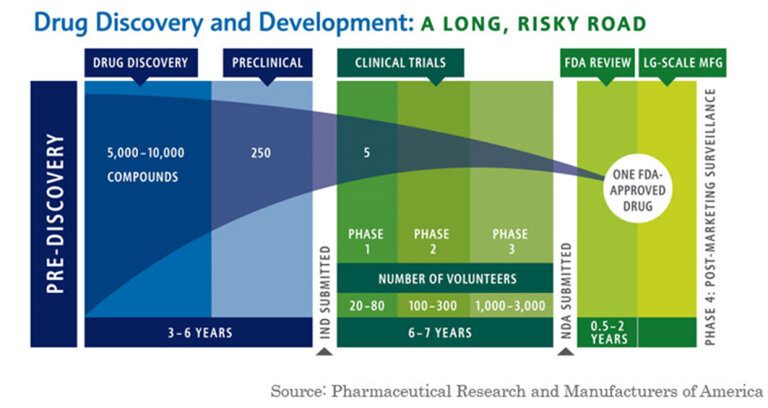

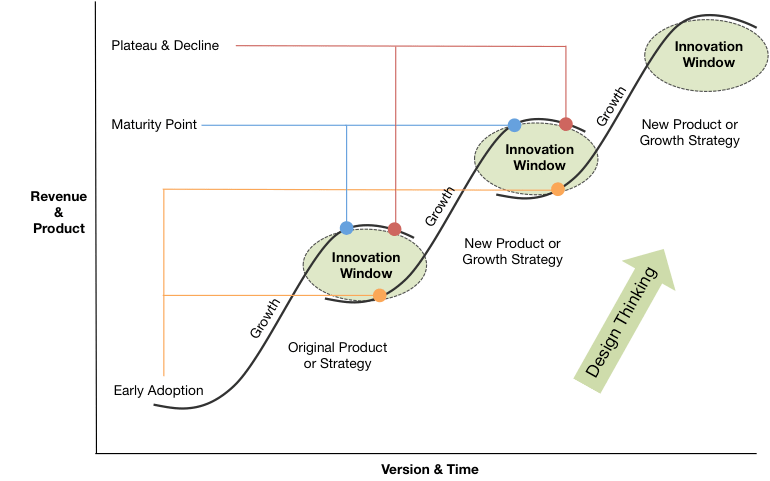

Patents, Generics, Biologics. Kolchinsky, who is the founder of leading biotech investment firm, RA Capital Management, lays out what he calls the Biotech Social Contract: “The drug development industry’s commitment to developing new medicines (and other technologies) that will go generic without undue delay is reciprocated by society’s commitment to providing universal health insurance with low/no out-of-pocket costs so that patients can afford what their patients prescribe.” Let’s unpack this straight forward contract. The first major idea presented is what Kolchinsky dubs the “Mountain of Generics.” When drugs are developed, they are often patented. Per the FDA, patents are normally granted for a 20 year period. Drugs can also have exclusivity, which are marketing rights - it prevents the submission and approval of Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) by the FDA. There are four types of exclusivity: 1 - Orphan Drug Exclusivity (7 years) for rare disases affecting <200,000 people 2 - New Chemical Exclusivity (5 years) for a new molecule that hasn’t existed before 3- Other Exclusivity for a change in new clinical investigations and 4 - Pediatric Exclusivity which is 6 months added to a patent/exclusivity when submitting pediatric study data. After patent expiration or exclusivity, drugs go “Generic”, meaning they become available in the public domain and companies can produce them without paying patent royalties. The process of going generic was fortified in the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act, an amendment to the Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act. Hatch-Waxman established that generic versions of previously approved innovator drugs can be approved without a full new drug submission. This sounds laudable, and for a short time massively increased the number of generic applications. However, Hatch-Waxman’s legacy is debated. Some argue that as a result of an easier genericization process, Pharmaceutical companies raised prices on branded drugs, exploited loop-holes in patent expiration (Jazz Pharma-REMS-Xyrem), and created patent thickets of similar patents that could prolong exclusivity. Because the loss of exclusivity or patents (sometimes referred to as the patent cliff) is so significant for Pharmaceutical companies, many go to extreme lengths to protect it. Further complicating the genericization of drugs, are new types of drugs known as biologics, which are not straightforward chemical formations (known as small molecule) but rather living engineered cells that are not effectively replicable. Because biologics are not a simple formulaic drug, genericization has actually been prolonged and biosimilars (generic biologics) have not come to market nearly as quickly as prior small molecule generic drugs. Humira, a $20B/year drug owned by Abbive, has sued multiple companies over genericization of its patents, leading to in some cases seven years of additional patent exclusivity. At $25B of sales, the biggest drug in the world is Merck’s Keytruda (used for treating cancer), whose patent expires in 2028. When drugs become generic, there is normally a fairly steep drop off in sales. Lipitor, Pfizer’s famous cholesterol statin generated $12.5B in sales at peak, but following patent expiration in 2011, dropped from $9.5B to just over $3B. Kolchinsky believes that we should celebrate the process of going generic. In his mind, as drugs become generic, they are added to our armory of infection fighting weaponry at much cheaper prices for everyone to access and benefit from. He believes we should incentivize going generic sooner, through upfront payments (6 months of sales) and close many of the patent loop-holes and litigation techniques that have allowed Pharma companies to continually prolong genericization.

Prices. Nobody ever says drug prices are reasonable. They are always too high. While we layout the reason why the system incentivizes higher prices below, let’s talk about some of the confusing aspects of drug prices. First of all, lets clearly state that retail prescription drug costs were about 9% of overall healthcare expenditure in 2022. Kolchinsky discussed; “Collectively, service-related costs account for the vast majority of healthcare spending, over 70%, far more than we spend on drugs.” While patented monopolies have pushed drug prices higher, hospital care, physician services, nursing facilities, and other healthcare services spend is unimaginably bloated and is a big driver of increased healthcare costs. As he points out, if all currently branded drugs went generic, and prices fell by 90%, that would be a one-time 6.7% reduction in healthcare spending. Billions of dollars for sure, but not as drastic a reduction as you would imagine. One of the big challenges with drug prices stems from how costs are negotiated between Pharmaceutical companies, distributors (Cencora, Mckesson, Cardinal) payers (insurance companies or government bodies like CMS (i.e. Medicare and Medicaid)), and Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs). The complicated miasma of different players causes obfuscation of prices but effectively there are gross prices and net prices. Net prices factor in rebates paid to PBMs and discounts offered to payers. Headline average list prices tend to go up every year with inflation or demand, but net prices can come down if payers negotiate more effectively. When we hear of price gouging, its not always clear whether we are talking about gross or net prices, and exactly why prices could go up for medications. Sometimes it is pure price gouging like Turing Pharmaceuticals in 2015. Other times, a drug may have been covered under a certain insurance plan or listed on a PBM’s formulary but is removed because the plan or PBM has negotiated better discounts on other drugs. Frequently, these are not one-for-one swaps, which causes huge headaches for patients. Another commonly, discussed issue with pricing is the increased cost of prices in the US relative to international prices. As Kolchinsky notes: “The US market accounts for roughly one third to one half of the drug industry’s revenue.” There are many causes of this 1) Administrative waste, roughly 8% of America’s budget is on administration compared to 1-3% for other countries 2) Education costs and higher salaries for providers mean prices must be higher for hospital to earn margin 3) Earlier access to medical innovations created in the US and 4) the decision to never deny patients access to treatment on the basis of their ability to pay. But perhaps the biggest reason for the higher drug prices is lack of single payer leverage. In countries with universal healthcare, countries negotiate directly with pharmaceutical companies to set prices, often based on comparative treatments and improvement in effectiveness of a new drug. These countries need to be willing to walk away from new innovations but they definitely achieve better overall prices. Kolchinsky argues that: “If companies could only sell in the US, they’d have to charge about twice as much to generate the same return on investment.” The US is trialing government led drug negotiations with the new passage of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022. It will be interesting to see what happens to prices!

Laws. There are numerous laws governing Healthcare and Pharmaceutical companies. The most important public laws include: the FD&C act of 1938 which gave authority to the FDA to regulate the safety of food, drugs, and medical devices, the 1965 Title XIX Amendment to the Social Security Act, establishing Medicare and Medicaid and their overseeing body, CMS, the Orphan Drug Act of 1983, which established longer market exclusivity and fast-track FDA approvals for drugs that target rare diseases (i.e. populations of less than 200,000 US Citizens), the American with Disabilities Act of 1990 which made it illegal to discriminate based on disabilities, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 that mandated guidelines around sharing personably identifiable information (PII) in the healthcare setting, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010 that broadened Medicaid eligibility and created state by state insurance exchanges for citizens to find insurance. Each of these laws fundamentally changed the healthcare landscape. The Orphan Drug Act has become a major bellwether to the Pharmaceutical industry, granting market exclusivity for 7 years and allowing pharmaceutical companies to charge a fair (but normally high) cost, based on the number of patients. Because these markets serve so few patients, Pharma companies need to know that if they are successful, they will be able to charge a high-enough price to recoup their R&D investments. When you couple the high prices, low market penetration, and exclusivity, these drugs can be very strong supplements to larger mass-market drugs that dominate the large pharmaceutical companies. About half of annual new drug approvals are for Orphan diseases. These drugs can make serious money: Imbruvica (Ibrutinib - cancer), Trikafta (elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor, Cystic Fibrosis), Lynparza (Olaparib, Ovarian Cancer) are all $5B+ drugs. Laws are always changing, and as part of the Inflation Reduction Act signed in 2022, a new law allowed DHS to negotiate prices directly with the Pharmaceutical manufacturers (going around Insurance, wholesalers, and PBMs), in an effort to reduce price growth. The first round of negotiations is set to occur in 2024 and could lead to substantial savings. The Healthcare landscape is constantly changing, to understand what’s happening, you have to follow the laws.

Business Themes

Why are drug prices so high? Incentives. Drug prices in the US are high because it behooves all players (except patients) involved to increase prices. There is a very complex web of institutions involved in the healthcare and pharmaceutical world: Pharmaceutical companies, biotech companies, insurance companies, providers (hospitals, care facilities), pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), drug wholesalers, beneficiaries (patients) and more. Patients and plan sponsors (employers a lot of the time) pay premiums to Health Plans (insurance companies). These Health Plans pay Pharmacy Benefit Managers who negotiate which drugs are placed on the Health Plan’s formulary, or what drugs are available to patients in the plan and their cost. Pharmacy Benefit Managers sit in between insurance companies, pharmacies, wholesalers, and drug manufacturers, negotiating discounts with everyone across the chain. You may be saying: “Wow, cheaper healthcare prices would be great!” However, in practice the value of PBMs is highly debated. PBMs make money primarily through rebates and incentive payments from manufacturers. Now, here we have an incentive mismatch. PBMs are paid a percentage of the “dollars saved” for plans and the incentive payments from manufacturers. Therefore, they prefer to have very high gross prices, for which they can negotiate steep discounts and capture more rebates. In addition, they may prefer to keep higher cost branded drugs on formularies even if there are generics available. For Example, the Center for Biosimilars notes that PBMs have continued to favor Abbvie’s drug Humira despite biosimilars being available: “IQVIA had discovered that adalimumab biosimilars could have offered potential savings of up to $6 billion to the US health care system. However, transitioning all US patients to these biosimilars would have resulted in an estimated 84% decrease in PBM profits. This shift also would have posed a potential loss of revenue for large specialty pharmacies, which frequently shared corporate ownership with PBMs.” Now, there are more players who prefer higher prices in this value chain. Wholesalers make money by buying large amounts of drugs in bulk and distributing them to the pharmacies. These wholesalers tend to make higher spreads (the cost of what they buy vs. the price they sell to pharmacies) on branded drugs but more money on generics distribution, given that generics make up a much larger percentage of drugs consumed. As Pharmaceutical companies increase drug prices, wholesalers benefit because they confidentially negotiate discounts to list prices with manufacturers. They then price drugs relative to the manufacturer list price, called the Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC). For example, they may negotiate a 10% discount to list price, then sell drugs at WAC - 5% to pharmacies, thereby profiting 5% on the drug. Manufacturers also obviously prefer higher prices so they can make more profits. Insurance companies like higher prices overall, because they can charge higher premiums as costs rise. At each stop, the players prefer higher prices. The price issues are worsened by the industry concentration: The top 3 PBMs managed 80% of the market, the top five pharmacies are 54% of the market, the top 3 wholesalers are 90% of the market, the top 20 pharma manufacturers own 70% of the market. There are very few players and all can coordinate to raise prices continuously. Furthermore, everyone in the industry claims to be trying to lower costs and they often provide eachother as scapegoats. BCBS (an effective insurance monopoly in many states) blames the Hospitals seeking more reimbursement. Mark Cuban has started Cost Plus Drugs which hopes to circumvent this complex web of increasing prices and provide generic drugs at very cheap costs to consumers.

Insurance. The biggest issue facing health insurance in the US is the lack of coverage for large swaths of the population. Today, 7% of Americans or 25.3m people are uninsured. Because a lot of the population remains uncovered, drug costs are higher for everyone. To understand why, consider a sick patient without insurance. When they receive medical care, they will have to pay out-of-pocket. Many times, particularly in emergency settings, patients are unable to cover the costs associated with their treatment. A large swath of the uninsured population are uninsured because they do not have enough money to pay insurance premiums and co-pays. When a patient is unable to pay, the Hospital tries to collect. Experts estimate there is about $80-$140B in past due medical debt in the US. But when they can’t collect, they are forced to eat the costs of providing this service. To recoup these costs, they raises prices elsewhere. In addition, Insurance companies charge co-pays for two primary reasons 1) to prevent overutilization of care and 2) to lower premiums across their population. Co-pays do act as a deterrent to individuals seeking medical care but that creates more sick patients. Rather than utilizing a medication that would heal an issue, a patient may not be able to afford the copay and elect to not take the medicine. In a few years, the condition worsens and they have a prolonged hospital stay which costs them significantly more than the combined copay costs. There should be some copay for doctor visits to modestly deter frequent vistits but drug costs should definitely not have associated copays. Copays create sicker populations. Kolchinsky proposes getting everyone insured and removing copays on prescription medications, which he believes will lessen medical debt, lower the out of pocket costs of healthcare, and increase the health of the US population. Another challenging aspect of insurance, is the concentration within states. The 2023 Competition in US Health Insurance Markets showed that 73% of commercial markets were highly concentrated. Concentration increases market power and allows insurers to charge higher premiums. For example, Blue Cross Blue Shield insurers, which are licensed in single states, are the largest plans in 41 states. Concentration raises premiums and lowers the prices paid to physicians, allowing insurance companies to make more profit. Another challenge is vertical integration. UnitedHealthcare has a 14% market share in the US (the largest), but it is also a physician network, a data analytics company, and a large PBM. They have utilized their data and wide range of services to gouge individuals and governments, by bill-coding for services and treatments that patients don’t actually need. Health Insurance is in need of major changes.

Pharma Marketing. Historically, Pharmaceutical companies promoted drugs directly to patients. However, in the early 1980s, as this practice became more widespread and egregious, the FDA eventually shut down DTC ads. It eventually came out with regulations surrounding advertising: Claims 1) cannot be false or misleading 2) must present a balance of risks and benefits 3) must state facts that are material to the advertised uses; and 4) must include every risk from the product’s approved labeling. Marketing to consumers can be dangerous. It could lead consumers into inappropriately asking for specific drugs they’ve been marketed and make it seem like drugs will always fix the specific conditions they are trying to treat. Pharmaceutical companies also market directly to physicians. As with DTC advertising, physician marketing has its issues. It could make medical professionals aware of new medications and help educate them about new treatments. But it can also devolve into kick-back schemes and unintend consequences. Let’s review a positive and negative example of Pharma marketing. EpiPen’s were first approved in 1987 and were initially sold at a low price, generally going underperscribed by the medical community. In 2007, Mylan acquired the generics business of Merck KGaA for $6.7B. EpiPen, now 20 years past approval was now a generic medication. Mylan still viewed EpiPen’s as underutilized by society. Through three net price increases, they grew EpiPen’s cost and profits, but used the excess funds to market the appliance aggressively and lobby for laws that required EpiPen training for schools. This grew EpiPen into a $1B drug by 2018. Today, EpiPen’s are still a ~$800m per year drug. While the raising costs for generic medications is certainly profit-seeking, growing knowledge and usage of potentially life-saving EpiPens is commendable. But similar tactics with a different drug created disastrous results. Purdue Pharma, the makers of the highly addictive opioid OxyContin, aggressively marketed their drugs through weekend physician meetings, dinners, conferences, and aggressive medical ads. Furthermore, the Purdue executives got the FDA to include a label that stated “Delayed absorption, as provided by OxyContin tablets, is believed to reduce the abuse liability of a drug.” These aggressive marketing and lobbying practices that supposed the drug was not addictive got thousands of individuals hooked on the drugs, created the opioid abuse scandals of the last decades. Purdue has faced over $8B in fines and $634m in individual fines for all of its perverse marketing practices. Pharma marketing is ultimately a good and bad thing. When abused its horrendous, when used properly it can promote the up-take of helpful medications.

Dig Deeper