This month we dive back into the world of payments and take a refreshed look at how payments companies work.

Tech Themes

Authorization. How do credit card’s even work? What is on the magnetic stripe? It turns out that each stripe has an alternating set of tiny magnets on it that produce a magnetic field around the card. The card reader on a POS system is a solinoid; when the magnets swipe through the solinoid it creates a change in the magnetic field also known as magnetic flux. The POS processes the changes in current as its swiped through the Solinoid, and is able to understand the credit card via common card standards, created by ISO. The challenge that existed with the internet, is how to ensure safe transactions when you are paying someone you clearly don’t know. The card companies created something called the card verification value (CVV), an extra number directly intended NOT to be written anywhere except for the back of your credit card. CVV codes were originally created by an Equifax employee in the UK, and initially rolled out by NatWest bank, eventually expanding to Mastercard (1997), Amex (1999), and Visa (2001). However, the early internet still had a massive fraud problem, as Roelof Botha discussed about Paypal in his Tim Ferris podcast appearance. In addition, card authorization was still quite difficult in Europe, where you would frequently have to call to provide authentication for cross-border purchases. In 1993, Europay, Mastercard, and Visa formed EMVco, to add additional fraud protection to cards. They were subsequently joined by other key members including American Express, Discover, JCB International, China UnionPay. Europay eventually merged with Mastercard in 2002 prior to Mastercard’s IPO. EMVco creates a standard for EMV chips, which embed small integrated circuits that produce a single-use cryptographic key for a merchant to decrypt and authorize a transaction. It is also incredibly difficult to clone a chip card, whereas magnetic stripes are fairly easy to copy. The increase in fraud protection was so great that it caused a liability shift, whereby the merchant (rather than the issuer) could become liable for fraud if a EMV chip card was not used, and a swipe was used instead. The latest innovation in card security is 3D Secure 2, which “allows businesses and their payment provider to send more data elements on each transaction to the cardholder’s bank. This includes payment-specific data like the shipping address, as well as contextual data, such as the customer’s device ID or previous transaction history.” The 3D Secure 2 also improves the UX of its “challenge flow,” which is an instance when a frictionless authentication wasn’t possible, for whatever reason. The challenge flow forces the user to authenticate the transaction through their banking application of choice, which is much more secure than just approving every transaction the network sees. Every day payments become more at risk and more secure!

Zelle and banks Funded Payments. Similar to Visa and Mastercard, Zelle is a cash transfer system originally created by a consortium of banks. In 2011, Bank of America, JP Morgan, Wells Fargo, and several other banks built a Paypal competitor called clearXchange. The new company would charge financial institutions to use the service, with most banks assuming the charges on behalf of their consumers. At the time, Venmo was beginning to take off with consumers utilizing its simple Peer-to-peer payments service. In 2012, Braintree acquired Venmo for just $26m. The low purchase price was the result of a lack of coherent business model, given Venmo’s founding by college roommates who were looking to send money easily. Later, in 2013, Braintree was acquired by Paypal for $800m. Braintree is an acquirer processor and introduced a business model to Venmo, namely investing the float of customer funds held in the Venmo ecosystem. In 2016, clearXchange was acquired by another bank run service called Early Warning Service, which provides risk management services to many financial institutions. Early Warning was itself created in 1990 by Bank of America, BB&T, Capital One, JP Morgan, and Wells Fargo. Early Warning launched Zelle in 2017, utilizing clearXchange’s underlying technology. Zelle is now massive, processing over $1m in volume a minute, which is more than competitors Venmo and Cash App. Zelle’s most recent stats are mind-blowing: 2.3B payments with $629B in volume. Look at creation of zelle and other examples of banks creating new companies (like visa/mastercard)

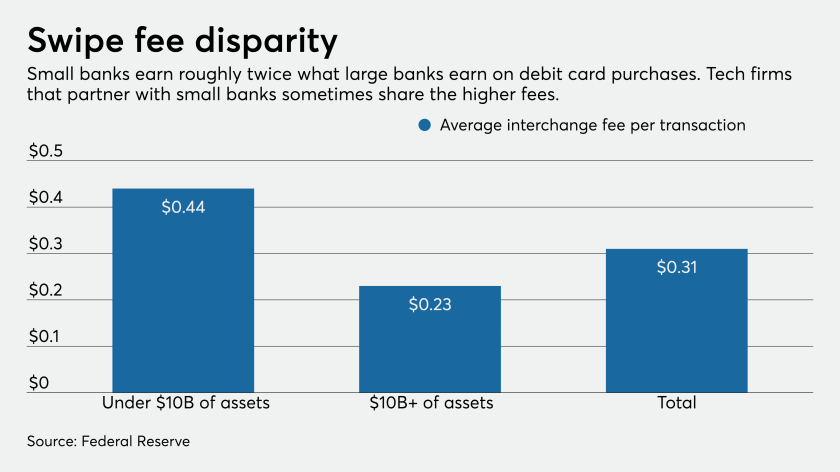

Money for Nothing, SaaS for Free. A new brand of payments companies are popping up that seek to turn a traditional SaaS model on its head. Divvy, the spend management platform, gives its SaaS software away for free, instead monetizing just the payments processed through its product. Its quite wild to see a company build complex software just to give it away, right? This strategy has been copied many times over, as we talked about when discussing Netscape and Slack. Whether its open source or just free commercial software, the free-ness of it makes it attractive. However, if everyone is free, then you still have to compete on merit. Ramp, a competitor to Divvy, raised $750m at an $8.1B valuation in 2022, and processed over $5B in payment volume in 2021. Divvy was acquired by Bill.com in 2021 for $2.5B in a mix of cash and stock. At the time of acquisition Divvy was doing just over $100m of annualized revenue, and about $4B of TPV, suggesting a take rate of ~2.5%. Ramp allegedly did about $100m in annualized revenue in 2022. While Divvy was able to find a successful exit through a willing buyer (a buyer who’s stock has declined 65% from all time highs), I’m not sure Ramp will find an easy buyer at $8.1B, but it may find the public markets if it can market itself as a cost-saving, AI, finance play. I’m just not sure that you can build a really big business by only processing payments and giving away complex software for free. We will see in time!

Business Themes

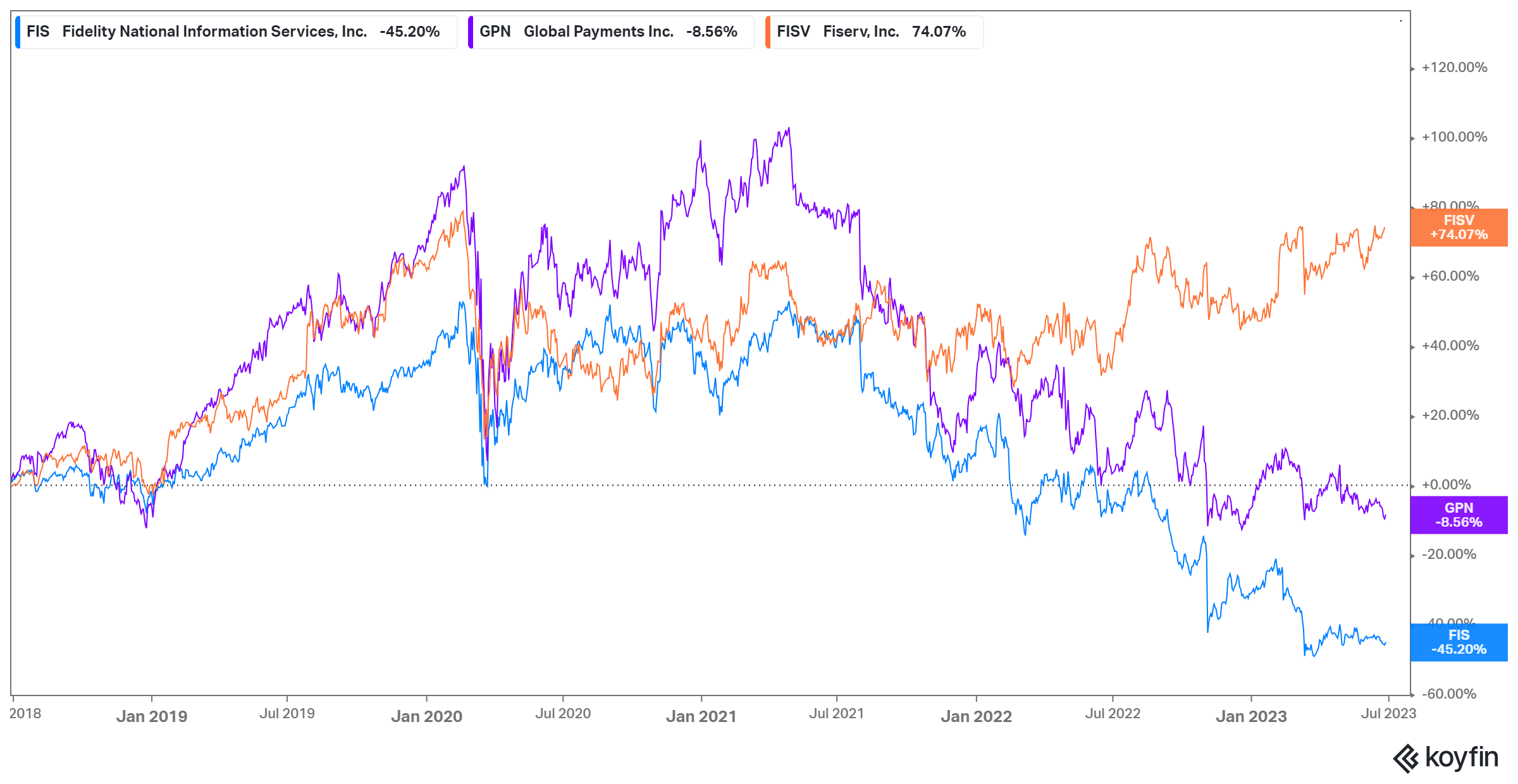

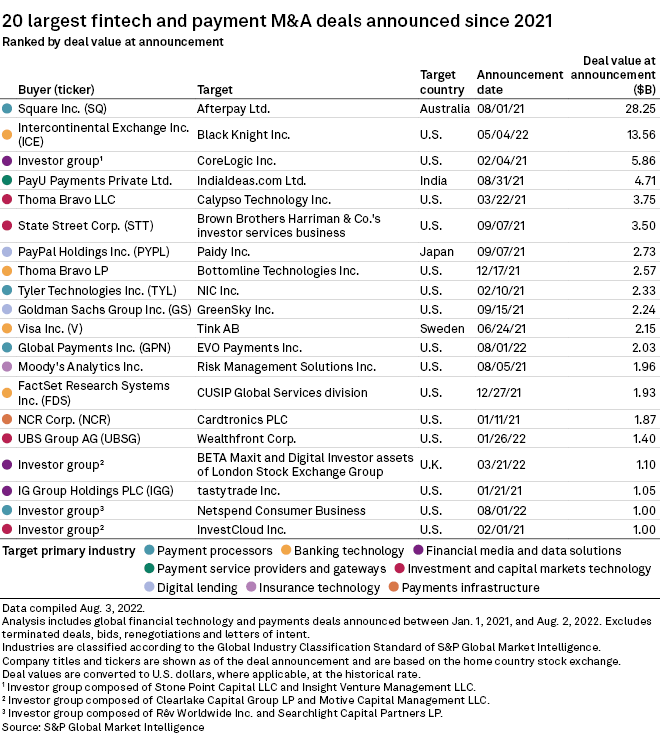

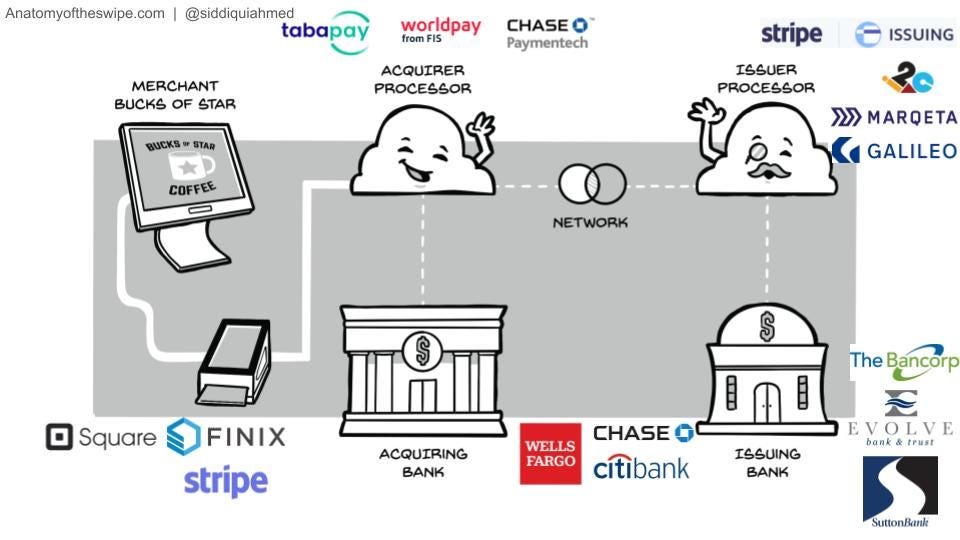

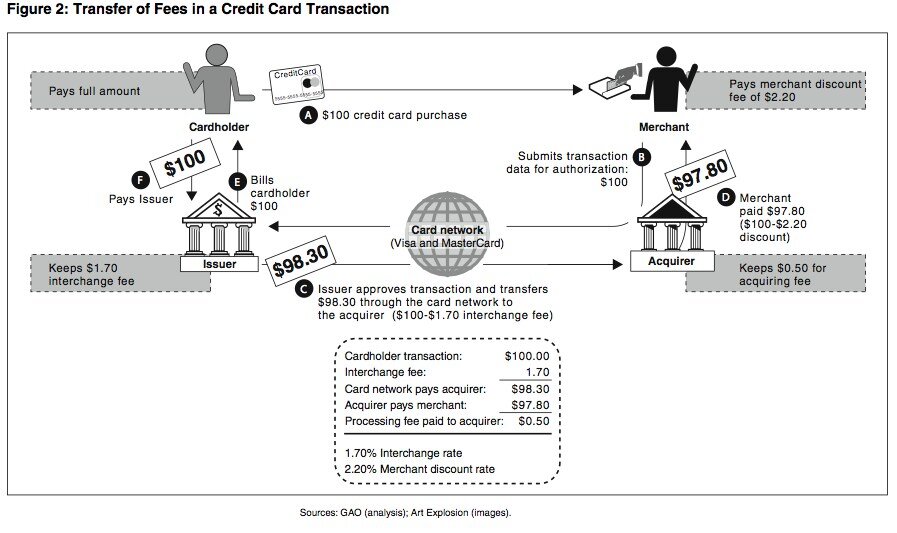

Issuer, Issuer Processor, Acquirer, Acquirer Processor. The arc of an individual payment can be broken into its constituent parts. The Issuer is normally a bank that issues credit cards to its banking customers. A bank may use an issuer processor to manage a connection to the card networks (like Visa and Mastercard) and accept/decline transactions. Examples of issuer processors include Marqeta, TSYS, and Galileo. Global Payments and TSYS merged in 2019, in an absolutely massive $21.5B deal, after Fiserv acquired FirstData for $22B and Fidelity National Services acquired WorldPay for $34B. 2019 was definitely a banner year for payments mergers, but signs of strain are already happening, with FIS announcing they’d be spinning out WorldPay in 2023. Back to our transaction - the merchant will have a payment terminal of some sort, and will use an acquirer processor like Chase Paymentech, Tabapay, or Fiserv, that will also have a fast connection to the card networks to request approval for a transaction. Lastly, we have the acquiring bank, the merchant’s bank account. When we look back at these big deals, its clear that each player was trying to round out its processing capabilities - TSYS (issuer processor) with Global Payments (a merchant acquirer), Fiserv (merchant acquirer) with First Data (issuer processor), and FIS (issuer processor) with WorldPay (merchant acquirer). FIS, Fiserv, and Global Payments have struggled to win over investors over the last five years, following these big deals.

Chargebacks. When a consumer doesn’t want to pay for an item, it can request a chargeback. The reasons for a chargeback can be numerous and valid, including fraud, item not as described, duplicate transactions, and more. In the event of fraud, a cardholder would dispute the charge with their bank. The bank would freeze their card and file a chargeback with the card network (Visa as an example). Visa would send a provisional credit to the customers card and take the money back from the merchant, then it would send the chargeback request detail to the merchant. If the merchant doesn’t dispute the chargeback, it will be assessed a $25-35 chargeback fee by Visa. However, if it does dispute the chargeback, and correctly can identify that the card actually did purchase the goods, then the issuer, the bank that is “underwriting” credit to the consumer, can be put on the hook for the funds used for the purchase. I never knew that both the merchant and issuer can be on the hook for chargebacks, but not the network! Another way in which Visa and Mastercard make money through the ecosystem!

Marqeta’s confusion. For our first payments book, we took a look at several of the new players in the credit card ecosystem, including Marqeta, Adyen, and Stripe. Its been quite a two years! Marqeta went public in June 2021, valuing the company at $15B. Stripe raised additional funds at a $95B valuation, and Adyen’s valuation hit $98B! But oh how the times change! Just two years later, and Stripe’s valuation is back at $50B, including a massively dilutive $6.5B raise to pay for employee taxes in option conversion. Adyen’s valuation sits at $53B today, a close to 50% decline, despite growing EBITDA 16% to 728M in 2022.. Marqeta may have had the worst time of all, which is said because Ahmed Siddiqui, worked at Marqeta for a number of years. Marqeta’s stock fell 85%, its CEO/Founder left the company, its gross margins have compressed from high 40’s back to down to low 40s, and its main customer Block has become an even larger customer, now driving 77% of its revenue. Marqeta went from next generation issuer processor and Stripe wannabe to an outsourced custom development shop for Block. My guess is its actual reputation sits somewhere in between the two. Expectations for Marqeta have fallen off a cliff, and its market cap sits at a tiny $2.6B. I’m not sure Block would be an immediate acquirer, because the market for issuer processing is incredibly competitive and Block has had its own stock price troubles. A spun out WorldPay could make sense as an acquirer. Visa would have made sense as acquirer, because it owns about 2.5% of Marqeta and has for many years, but their recent acquisition of Pismo, believed to be a LATAM focused and better version of Marqeta. It’s unlikely Marqeta will exist long as a small solo issuer processor!

Dig Deeper